Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the No. 1 cause of preventable deaths in hospitals, and 60% of all VTE cases occur during or following hospitalization, according to Jeffrey I. Weitz, MD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

, he said in a webinar to promote World Thrombosis Day.

“To prevent VTE, people need to be aware of the problem,” he said. Hospitalization for any reason increases the risk of VTE, but thromboprophylaxis may be underused in medical patients, compared with surgical patients, because most surgical patients are automatically considered at risk.

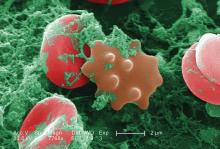

Prevention of VTE involves understanding the risk factors, Dr. Weitz said. He pointed to a triad of conditions that promote clotting: slow blood flow, injury to the vessel wall, and increased clotability of the blood.

In a study of VTE risk factors, recent surgery with hospitalization and trauma topped the list, but hospitalization without recent surgery was associated with a nearly 8-fold increase in risk (Arch Intern Med. 2000;160[6]:809-15).

Evidence supports the value of anticoagulant prophylaxis, Dr. Weitz said. In a 2007 meta-analysis, use of anticoagulants reduced the risk of VTE by approximately 60% (Ann Intern Med. 2007 Feb 20;146[4]:278-88), and a 2011 update showed a reduction in risk of approximately 30% (Ann Intern Med. 2011 Nov 1;155[9]:602-15).

While risk assessment remains a challenge, several models can help, said Dr. Weitz.

Current guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians suggest a shift toward individualized assessment of VTE risk, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services mandates VTE risk assessment, Dr. Weitz said.

He offered seven steps to improve prophylaxis in the hospital:

1. Obtain commitment from hospital leadership, including formation of a committee.

2. Have a written hospital policy on thromboprophylaxis.

3. Keep the policy simple and standard in terms of who gets prophylaxis and when.

4. Use order sets, computer order entry, and decision support.

5. Make the prophylaxis decision mandatory.

6. Involve of all the members of the care team and patients.

7. Use audits to measure improvement.

Several risk assessment models for VTE in hospitalized medical patients have been studied, including the Padua and IMPROVE models, Dr. Weitz said. For any model, factoring in the D-dimer can provide more information. “If D-dimer is increased more than twice the upper limit of normal, it is a risk factor for VTE,” he said.

Another consideration in thromboprophylaxis involves extending the duration of prophylaxis beyond the hospital stay, which is becoming a larger issue because of the pressure to move patients out of the hospital as quickly as possible, Dr. Weitz said. However, trials of extended thromboprophylaxis have yielded mixed results. Extended doses of medications, including rivaroxaban, enoxaparin, apixaban, and betrixaban can reduce the risk of VTE, but can also increase the risk of major bleeding.

“I think at this point we are not yet there at identifying patients who should have thromboprophylaxis beyond the hospital stay,” Dr. Weitz said.

But VTE risk should be assessed in all hospitalized patients, and “appropriate thromboprophylaxis is essential for reducing the burden of hospital-associated VTE,” he said.

Dr. Weitz encouraged clinicians to explore more resources for managing VTE risk at worldthrombosisday.org.

Dr. Weitz reported relationships with companies including Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, Portola, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Servier. He also reported research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Canadian Fund for Innovation.