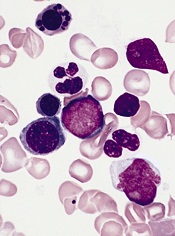

showing anemia

Measuring levels of the hormone hepcidin can help us distinguish anemia caused by iron deficiency from anemia caused by other conditions, a new study suggests.

Investigators say the findings, published in Science Translational Medicine, could help public officials make more informed decisions about distributing iron supplements.

Giving iron supplements to individuals who don’t need them can promote or exacerbate malaria and other infections.

With this research, the investigators linked low levels of hepcidin to iron-deficiency anemia in preschool children living in Africa.

Sant-Rayn Pasricha, PhD, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and his colleagues tested hepcidin levels in 1313 samples taken in 2001 and 2008 from children in The Gambia and Tanzania, respectively.

The team also looked at retrospective data from 25 Gambian children with either postmalarial or nonmalarial anemia.

The mean hepcidin level was significantly lower in children with iron-deficiency anemia than in children with anemia due to inflammation/infection (1.8 ng/mL and 21.7 ng/mL, respectively; P<0.0001).

To expand upon this finding, the investigators modeled the potential impact of screening children for iron supplementation needs based on hepcidin levels rather than anemia status.

If a screen was based on the presence of anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/dL), 77% of iron-deficient children would have received iron supplements, but so would 73% of children with Plasmodium falciparum parasitemia and all of the children with anemia due to inflammation.

On the other hand, if a screen was based on a hepcidin cutoff of <5.5 ng/mL, iron supplements would be given to 77% of children with iron deficiency, 80% of children with iron-deficiency anemia, 20% of children with P falciparum infection, and 14% of children with anemia due to inflammation.

The investigators noted that a lower hepcidin cutoff would have reduced the proportion of individuals with infection and/or inflammation receiving iron, but it would have increased the risk that more children with iron-deficiency anemia would not receive iron. And of course, the reverse is true of a higher hepcidin cutoff.

Nevertheless, the team believes these results are promising. They are now conducting clinical trials to test whether hepcidin levels can be used as a marker to guide iron supplementation decisions.