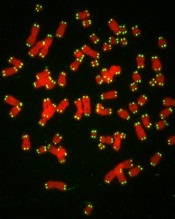

with telomeres in green

Credit: Claus Azzalin

Measuring the length and function of telomeres can help us predict prognosis in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to research published in the British Journal of Haematology.

Investigators found that CLL patients with short, dysfunctional telomeres had a considerably poorer clinical outcome than those with long, functional telomeres.

“For the first time, confident predictions of clinical outcome can be made for individual CLL patients at diagnosis based on accurate analysis of the length of telomeres in cancer cells,” said Chris Pepper, PhD, who led the research at Cardiff University’s School of Medicine in the UK.

“This should prove enormously valuable to doctors, patients, and their families, and there is no reason why there should not be widespread implementation of this powerful prognostic tool in the near future.”

CLL progression is known to be sped up by the loss of telomeres, which cap the ends of chromosomes and protect them from damage when a cell divides. Every time a cell divides, telomeres get shorter.

When they become too short in a healthy cell, signals are sent to instruct the cell to stop dividing and die. But this “safety check” does not occur in CLL cells. Telomeres become so short that chromosomes are left exposed and are prone to fusing together during cell division, causing even larger DNA faults and even greater instability.

So Dr Pepper and his colleagues set out to identify the telomere length at which fusions start to occur in CLL patients.

The team measured telomeres in patient samples using single telomere length analysis (STELA) along with an experimentally derived definition of telomere dysfunction. They defined the upper telomere length threshold at which telomere fusions occur and used the mean of the telomere “fusogenic” range as a prognostic tool.

The researchers first analyzed samples from 200 CLL patients and found that patients with telomeres below the fusogenic mean had significantly shorter overall survival than patients with telomeres above the fusogenic mean (hazard ratio [HR]=13.2, P<0.0001). This was also true for patients with early stage disease (HR=19.3, P<0.0001).

The investigators confirmed this association by analyzing samples from an additional 121 CLL patients. The prognostic impact of telomere dysfunction was evident in the entire cohort (HR=7.4, P<0.0001) and among patients classified as Binet stage A (HR=8.9, P<0.0001).

The researchers also found they could use telomere dysfunction to accurately classify Binet stage A patients into an indolent disease group and a poor prognostic group. At 10 years, the survival rate was 91% in the favorable prognostic group and 13% in the poor prognostic group.

Of note, patients with telomeres above the fusogenic mean had superior prognosis regardless of their IGHV mutation status or cytogenetic risk group. And in a multivariate analysis, the telomere fusogenic mean was associated with the highest hazard of progression and death, independent of all other biomarkers.

“The accuracy of this test in predicting how a person’s disease will develop is unprecedented and, if confirmed in clinical trials, would help doctors decide on the best treatment courses for individual CLL patients,” said Matt Kaiser, PhD, Head of Research at Leukaemia & Lymphoma Research, which funded this study.

“Telomeres are known to play a part in the progress of other forms of cancer, so this type of testing could have far-reaching benefits.”