Sunscreens that have proven their protective ability and feature updated, more-consumer-friendly labeling are hitting store shelves, but they currently share space with older products that may not have passed muster with the Food and Drug Administration.

This mix of old and new packaging coincides with an FDA announcement that, later this year, it will review sunscreen ingredient safety and the potential approval of additional UVA-blocking agents.

In January, the agency issued its semiannual agenda for the coming year. That list included two sunscreen-related items.

The FDA said it would issue an "advance notice of proposed rulemaking" in July on how it will address sunscreen ingredient safety, which is the first step in a three-step process that culminates in a final rule.

The agency also said it would take a similar early step in the regulatory process for new ingredients manufacturers would like to add to their products.

At least six additional UVA filters are awaiting FDA approval, said Dr. Steven Q. Wang, director of dermatologic surgery and dermatology at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Basking Ridge, N.J. Currently, only two UVA-blocking agents – avobenzone and zinc oxide – are approved in the United States, but many others are available in Europe and elsewhere around the world.

Dr. Wang said he is looking forward to progress on UVA blockers; he noted that although both UVA and UVB contribute to skin cancer development, UVA penetrates deeper into the skin, contributes to more DNA damage, and plays a larger role in skin aging. A study of sunscreens from 1997 to 2009 by Dr. Wang showed that increasing numbers of products contained either avobenzone or zinc oxide, matching their claims of UVA protection.

In the late 1990s, 81% of the products surveyed claimed to protect against UVA, but only 5% actually contained a UVA blocker. By 2009, 80% of the products still made the claim, and 70% contained UVA-blocking agents. The study was published in the January issue of the journal Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences (Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2013;12:197-202).

Based on these findings, many of the products on the market in the past decade already met the FDA’s new criteria – announced in June 2011 – to claim protection against skin cancer, Dr. Wang said. And, clinicians and consumers should be reassured that products that meet the FDA labeling rules are effective and safe, he added.

Because they have already met the FDA’s effectiveness criteria, most products have not needed to be reformulated, said Farah Ahmed, chair of the sunscreen task force at the Personal Care Products Council.

But manufacturers have relabeled products to conform to the FDA’s rules, she said. The Council estimates that at least 4,500 products marketed in the United States claim an SPF, which subjects them to the FDA sunscreen rules. The product list includes not only sunscreens but lip balms, daily moisturizers, makeup, and any other product that contains a sunscreen component.

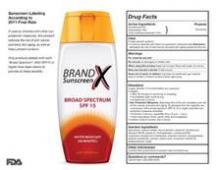

Products that have proved through testing that they protect against UVA and UVB radiation can claim that they are "broad spectrum" and will be labeled as SPF 15 or higher. The label also will be able to claim that the product can protect against sunburn, and, if used as directed with other sun protection measures, can reduce the risk of skin cancer and early skin aging.

Any product not labeled as "broad spectrum" or that has an SPF value between 2 and 14 will carry a warning: "Skin Cancer/Skin Aging Alert: Spending time in the sun increases your risk of skin cancer and early skin aging. This product has been shown only to help prevent sunburn, not skin cancer or early skin aging."

Under the revised labeling, no product can claim to be waterproof or sweatproof. If a product claims to be water resistant, the product’s label must state how long a user "can expect to get the declared SPF level of protection while swimming or sweating, based on standard testing," according to the FDA.

For more information, visit the agency’s website.

There may still be products on store shelves that have the old labeling, said Ms. Ahmed. That’s because the FDA has allowed a phase-in. Retailers also can choose to sell remaining stocks of the old products or remove them. "I think we’ll continue to see a mix of both products on the shelves," said Ms. Ahmed.

The situation creates the potential for confusion among consumers, although the FDA rules were meant to create a uniform label to help increase sun protection knowledge and the use of sun protection products.