Contaminated laundry led to an outbreak of cutaneous and pulmonary zygomycosis that killed three immunocompromised patients and sickened three others at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong.

The contamination was traced to a contract laundry service that was, in short, a microbe Disneyland. It was hot and humid, with sealed windows, dim lights, and a thick layer of dust on just about everything. Washers weren’t hot enough to kill spores; washed items were packed while warm and moist; and dirty linens rich with organic material were transported with clean ones (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Dec 13. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1006).

Of 195 environmental samples, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples. Freshly laundered items – including clothes and bedding – had bacteria counts of 1,028 colony forming units (CFU)/100 cm2, far exceeding the “hygienically clean” standard of 20 CFU/100 cm2 set by U.S. healthcare textile certification requirements.

Queen Mary didn’t regularly audit its linens for cleanliness and microbe counts. “Our findings [suggest] that such standards should be adopted to prevent similar outbreaks,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Vincent Cheng, an infection control officer at Queen Mary, one of Hong Kong’s largest hospitals and a teaching hospital for the University of Hong Kong.

It has since switched to a new laundry service.

The outbreak ran from June 2 to July 18, 2015, during Hong Kong’s hot and humid season, which didn’t help matters.

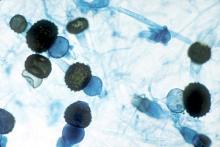

The six patients were 42-74 years old; one had interstitial lung disease and the rest were either cancer or transplant patients. Infection was due to the spore-forming mold Rhizopus microsporus. Two pulmonary and one cutaneous infection patient died.

Length of stay was the most significant risk factor for infection; the mean interval from admission to diagnosis was more than 2 months.

“Pulmonary zygomycosis due to contaminated hospital linens has never been reported.” Clinicians need to “maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,” the investigators said.

The U.S. recently had a cutaneous outbreak in Louisiana; hospital linens contaminated with Rhizopus species killed five immunocompromised children there in 2015.

“Invasive zygomycosis is an emerging infection that is increasingly reported in immunosuppressed hosts;” previously reported sources include adhesive bandages, wooden tongue depressors, ostomy bags, damaged water circuitry, adjacent building construction activity, and, as Queen Mary reported previously, contaminated allopurinol tablets.

Detecting the problem isn’t easy. None of the Replicate Organism Detection and Counting contact plates at Queen Mary recovered zygomycetes from the contaminated linen items. It took sponge swapping to find it; “without the use of sponge swab and selective culture medium, the causative agents in this outbreak would have been overlooked,” the investigators said.

Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors did not have any financial conflicts of interest.