NEW ORLEANS – An investigational endoscopic procedure that aims to disrupt how the gut absorbs nutrients according to principles of gastric bypass surgery achieved reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels and improvement in other key metabolic parameters in people with type 2 diabetes participating in a single-center investigational study in Santiago, Chile.

The procedure, called duodenal mucosal resurfacing (DMR), uses a balloon catheter to thermally ablate about 10 cm of the duodenal mucosa, Alan Cherrington, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“A lot of the gastric bypass surgeries have been very effective in not only creating weight loss but in improving glucose tolerance,” Dr. Cherrington said. “The problem is, of course, they are very invasive and difficult to do, so the hope here was to try and develop a technique which in fact would be simpler but perhaps achieve some of the same effects.”

The mucosa in people with type 2 diabetes has been known to be thickened, and the endocrine cells discommuted and morphed, Dr. Cherrington explained. “So the question was, is there a way to do something about that?” The procedure, he said, was “well tolerated” and achieved significant reduction of HbA1c after 3 months.

An international group of bariatric experts participated in the trial report. Dr. Cherrington said the procedure involves inserting a balloon-tipped catheter through the esophagus and stomach and into the duodenum, and then seating the balloon snugly in the mucosa at the ampulla of Vater. “You need a snug fit between the balloon and the mucosa,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Once the catheter is in place, it is filled with saline that inflates the balloon to fill the space. At that point, heated saline is run through the catheter for 10 seconds, creating a circumferential ablation of 300-500 mcm. When that step is completed, the balloon is moved down approximately 2 cm and the process repeated until the full 10 cm of the duodenal length from the ampulla of Vater to the ligament of Treitz is ablated.

A trained endoscopist performed the procedure with the patients under anesthesia, Dr. Cherrington said. The average HbA1c was 9.6% at baseline, and the 39 patients were on one or more antidiabetic agents. The average fasting plasma glucose was 187 mg/dL at baseline. Average age was 54 years, and two-thirds of patients were male.

“It was not a mechanistic study,” Dr. Cherrington said. “It was a study purely to see: Can we do this? Can it be done safely? And would there be any efficacy at all?” The patients actually received DMR of two lengths: a short-segment ablation of 3.4 cm (n = 11); and a long-segment approach of 9.3 cm (n = 28).

“Patients had no difficulty tolerating an oral diet within days of the procedure,” Dr. Cherrington said. He described the adverse events as “mild,” mostly occurring immediately after the procedure. They typically involved tenderness due to anesthesia intubation or the endoscopic procedure itself, resolving in 3 days. Three patients had stenosis “very early while the device was still in its iterative development,” Dr. Cherrington said. But since the device was modified, the episodes of stenosis were mild and “resolved easily” with dilation.

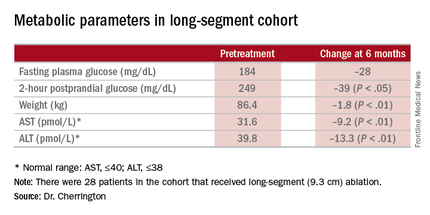

The 9.3-cm ablation achieved better outcomes than did the 3.4-cm ablation, Dr. Cherrington said. Those in the long-segment group with baseline HbA1c as high as 11% averaged 7.5% 3 months post ablation; those with HbA1c around 9% before ablation averaged “just below 7%” afterward, he said. The patients showed some “waning effect” in HbA1c after 6 months.

A cohort of patients who continued their medications achieved even better results. “They came to an HbA1c of 6.5% and drifted up minimally at 6 months,” Dr. Cherrington said. “Part of the drift upward of the others was a function that they began to come off their medications.” Other reported metabolic parameters also showed improvement.

The next step, Dr. Cherrington said, is to compile 6-month results in an ongoing trial called Revita-1 in Chile and at five centers in Europe; after that, the goal is to conduct a multicenter phase II trial, Revita-2 that will include U.S. centers. “Clearly there are many, many questions that remain to be answered, and further examination of the efficacy, of the safety, of the clinical utility, and not the least of which is what is the mechanism by which this comes about, is essential,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Dr. John M. Miles of the University of Kansas Hospital in Kansas City gave a preview of some of those questions: “I would love to know whether metformin pharmacokinetics are altered by this procedure.” Dr. Miles asked for an explanation of the initial weight loss in study patients. “I would love to see self-reported calorie counts with these people,” he said.