After 2 years of a pandemic in which traveling was barely possible, tropical diseases are becoming important once more. At a 2022 conference for internal medicine specialists, tropical medicine specialist Fritz Holst, MD, of the Center for Tropical and Travel Medicine in Marburg, Germany, explained what questions you should be asking travelers with a fever at your practice and how to proceed with a suspected case.

The following article is based on the lecture: “Differential Diagnosis of Fever After a Trip to the Tropics,” which Dr. Holst gave at the 128th conference of the German Society of Internal Medicine.

A meta-analysis of studies concerning the topic, “returnee travelers from the tropics with fever,” was published in 2020. According to the analysis, purely tropical infections make up a third (33%) of fever diagnoses worldwide following an exotic trip. Malaria accounts for a fifth (22%), 5% are dengue fever, and 2.2% are typhoid (enteric fever).

In 26% of the returnee travelers investigated, nontropical infections were the cause of the fever. Acute gastroenteritis was responsible for 14%, and respiratory infections were responsible for 13%. In 18% of the cases, the cause of the fever remained unclear.

In Germany, the number of malaria cases has increased, said Dr. Holst. In Hessen, for example, there was recently a malaria fatality. “What we should do has been forgotten again,” he warned. More attention should also be paid once more to prophylaxis.

How to proceed

Dr. Holst described the following steps for treating recently returned travelers who are sick:

- Severely ill or not: If there are signs of a severe disease, such as dyspnea, signs of bleeding, hypotension, or central nervous system symptoms, the patient should be referred to a clinic. A diagnosis should be made within 1 day and treatment should be started.

- Transmissible or dangerous disease: This question should be quickly clarified to protect health care personnel, especially those treating patients. By using a thorough medical history (discussed below), a range of diseases may be clarified.

- Disease outbreak in destination country: Find out about possible disease outbreaks in the country that the traveler visited.

- Malaria? Immediate diagnostics: Malaria should always be excluded in patients at the practice on the same day by using a thick blood smear, even if no fever is present. If this is not possible because of time constraints, the affected person should be transferred directly to the clinic.

- Fever independent of the travel? Exclude other causes of the fever (for example, endocarditis).

- Involve tropical medicine specialists in a timely manner.

Nine mandatory questions

Dr. Holst also listed nine questions that clinicians should ask this patient population.

Where were you exactly?

Depending on the regional prevalence of tropical diseases, certain pathogens can be excluded quickly. Approximately 35% of travelers returning from Africa have malaria, whereas typhoid is much rarer. In contrast, typhoid and dengue fever are much more widespread in Southeast Asia. In Latin America, this is the case for both dengue fever and leptospirosis.

When did you travel?

By using the incubation time of the pathogen in question, as well as the time of return journey, you can determine which diseases are possible and which are not. In one patient who visited the practice 4 weeks after his return, dengue or typhoid were excluded.

Where did you stay overnight?

Whether in an unhygienic bed or under the stars, the question regarding how and where travelers stayed overnight provides important evidence of the following nocturnal vectors:

- Sandflies: Leishmaniasis

- Kissing bugs: Chagas disease

- Fleas: Spotted fever, bubonic plague

- Mosquitoes: Malaria, dengue, filariasis

What did you eat?

Many infections can be attributed to careless eating. For example, when eating fish, crabs, crawfish, or frogs, especially if raw, liver fluke, lung fluke, or ciguatera should be considered. Mussel toxins have been found on the coast of Kenya and even in the south of France. In North African countries, you should be cautious when eating nonpasteurized milk products (for example, camel milk). They can transmit the pathogens for brucellosis and tuberculosis. In beef or pork that has not been cooked thoroughly, there is the risk of trichinosis or of a tapeworm. Even vegetarians need to be careful. Infections with the common liver fluke are possible after eating watercress.

What have you been doing?

You can only get some diseases through certain activities, said Dr. Holst. If long-distance travelers tell you about the following excursions, prick up your ears:

- Freshwater contact: Schistosomiasis, leptospirosis

- Caving: Histoplasmosis, rabies

- Excavations: Anthrax, coccidioidomycosis

- Camel tour: MERS coronavirus (Do not mount a sniffling camel!)

- Walking around barefoot: Strongyloides, hookworm

Was there contact with animals?

Because of the risk of rabies following contact with cats or biting apes, Dr. Holst advised long-distance travelers to get vaccinated.

Were there new sexual partners?

In the event of new sexual contacts, tests for hepatitis A, B, C, and HIV should be performed.

Are you undergoing medical treatment?

The patient may already be under medical supervision because of having a disease.

What prophylactic measures did you take before traveling?

To progress in the differential diagnosis, questions should also be asked regarding prophylactic measures. Vaccination against hepatitis A provides very efficient infection protection, whereas vaccines against typhoid offer a much lower level of protection.

Diagnostic tests

As long as there are no abnormalities, such as meningism or heart murmurs, further diagnostics include routine infectiologic laboratory investigations (C-reactive protein, blood count, etc), blood culture (aerobic, anaerobic), a urine dipstick test, and rapid tests for malaria and dengue.

To exclude malaria, a thick blood smear should always be performed on the same day, said Dr. Holst. “The rapid test is occasionally negative. But you often only detect tertian malaria in the thick blood smear. And you have to repeat the diagnostics the following day.” For this, it is important to know that a single test result does not exclude malaria right away. In contrast, detecting malaria antibodies is obsolete. Depending on the result, further tests include serologies, antigen investigations, and polymerase chain reaction.

Treat early

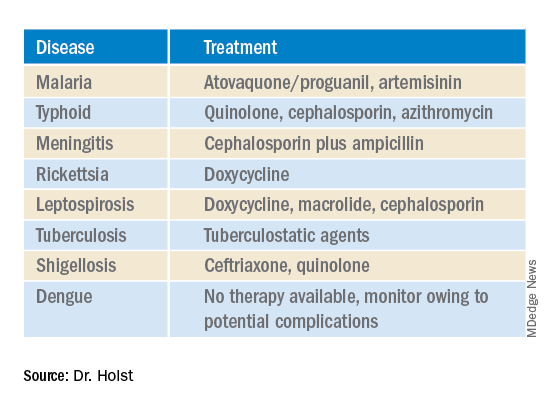

A complete set of results is not always available promptly. Experts recommend that, “if you already have a hunch, then start the therapy, even without a definite diagnosis.” This applies in particular for the suspected diagnoses in the following table.

This article was translated from Coliquio. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.