Three new regimens for preventing tuberculosis in HIV-infected adults appear effective, though no more effective than the standard 6-month course of isoniazid, according to a report in the July 7 New England Journal of Medicine.

All three new regimens facilitated adherence, however, which "could substantially increase the number of patients who receive and complete preventive therapy,"according to Dr. Neil A. Martinson of the division of infectious diseases, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his associates.

Results were more disappointing in a separate study of TB prophylaxis among HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children, which showed that preventive isoniazid was no better than placebo at improving TB-free survival in that age group.

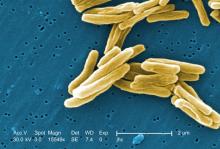

Tuberculosis is the most common opportunistic infection and the leading cause of death in adults and children infected with HIV, especially in Africa.

For adults, the World Health Organization endorses routine prophylaxis with 6 months of isoniazid, but the number of public health programs that provide such treatment is "exceedingly low," according to Dr. Martinson. The chief obstacle is concern about low therapy completion rates, which lead to both reinfection and the selection of drug-resistant mycobacterial strains.

To address these concerns, the investigators studied the use of a 12-week course of rifapentine (900 mg) given weekly or rifampin (600 mg) given twice weekly, both with isoniazid (900 mg), as well as long-term continuous administration of isoniazid (300 mg daily) for up to 6 years, which may be more potent than shorter courses of the drug and thus may prevent reinfection in areas in which TB is endemic, the investigators wrote.

These three regimens were compared against the standard prophylaxis, a 6-month course of isoniazid (300 mg daily), in 1,148 tuberculin-positive HIV-infected adults in South Africa. The median patient age was 30 years, and 83% were women.

The primary end point was tuberculosis-free survival. After a median follow-up of 4 years, there were no significant differences in this end point between any of the new regimens and the standard regimen, the investigators said. Incidences of active TB or death were 3.1/100 person-years in the rifapentine-isoniazid group, 2.9 in the rifampin-isoniazid group, and 2.7 in the long-term continuous isoniazid group, as compared with 3.6/100 person-years in the control group (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:11-20).

However, the shorter regimens had higher adherence rates, in part because treatment was supervised and adverse reactions were minimized.

The proportions of patients who reported taking more than 90% of their medication were 95.7% in the rifapentine-isoniazid group, 94.8% in the rifampin-isoniazid group, and 83.8% in the control group. Among patients in the long-term isoniazid group, 89.1% took their medication from the total follow-up time.

The shorter regimens did not appear to select for drug-resistant TB, but the number of cases that were cultured was relatively small, they noted.

In the second study, 548 HIV-infected infants and 804 uninfected but HIV-exposed infants aged 3-4 months were enrolled at three medical centers in South Africa and one in Botswana. All the infants had received bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination within 30 days of birth, before their HIV status had been determined, said Dr. Shabir A. Madhi of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and associates.

These study subjects were randomly assigned to receive daily isoniazid to prevent TB acquisition or placebo. The primary end point was TB-free survival at 96 weeks after randomization.

In the HIV-infected cohort, either tuberculosis or death occurred in 52 children (19%) in the isoniazid group, compared with 53 (also 19%) in the placebo group, indicating no beneficial effect for prophylaxis. A post hoc analysis also showed no benefit in subgroups of patients categorized by whether they had definite or probable TB infection.

The findings were similar for the HIV-exposed cohort, in which tuberculosis or death occurred in 39 children (10%) who received isoniazid and 45 (11%) who received placebo, a nonsignificant difference, Dr. Madhi and colleagues said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:21-31).

The findings indicate that, unlike adults, children do not benefit from isoniazid prophylaxis, they said.

Dr. Martinson’s study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center, and the U.S. Agency for International Development. Dr. Martinson reported receiving lecture fees from Alere. Dr. Madhi’s study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and the Secure the Future Fund of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Madhi and associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.