User login

Marijuana May Lower Death Risk After Acute MI

CHICAGO – Patients who reported using marijuana prior to experiencing an acute MI had significantly lower in-hospital mortality and were less likely to have cardiogenic shock or require an intra-aortic balloon pump than marijuana nonusers with an MI in an eight-state hospital records study, Dr. Cecelia P. Johnson-Sasso reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“If this observation is confirmed in independent studies, further investigation into the possible therapeutic benefit of cannabinoid receptor agonists in acute MI may be warranted,” declared Dr. Johnson-Sasso of the University of Colorado Denver.

She and her coinvestigators obtained hospital records with identity information removed for more than 3 million patients admitted for acute MI during 1994-2013 in eight states: California, Colorado, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Texas, Vermont, and West Virginia.

After excluding concomitant users of cocaine, methamphetamine, or alcohol due to the potential for confounding cardiotoxic effects; MI patients under age 19 because of the likelihood of congenital heart disease; and patients over age 70 because only 0.01% of them admitted to marijuana use, the investigators were left with a study population of 3,854 marijuana users and 1.27 million MI patients who hadn’t used marijuana.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders including baseline comorbid conditions, patient demographics, and payer status, the marijuana users prior to MI had a 17% reduction in in-hospital mortality, were 20% less likely to undergo intra-aortic balloon pump placement, and had a 26% reduction in shock. On the other hand, they were also 19% more likely than marijuana nonusers to be placed on mechanical ventilation. And even though they were equally likely to undergo diagnostic coronary angiography, they were 28% less likely than marijuana nonusers to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention. All of these differences were statistically significant and clinically meaningful.

She was quick to note the limitations of her study: No data were available on readmissions or late mortality, and it’s highly likely that marijuana use by patients with acute MI was significantly underreported during the study period, which was largely before the legalization movement took off.

With state marijuana laws rapidly changing and the legal pot industry becoming a big business, the lack of research into the health consequences of marijuana by disinterested parties has become glaringly obvious, according to Dr. Johnson-Sasso. Cannabinoid receptors are found not only in the brain, but in cardiac muscle, the kidney, liver, vascular and visceral muscle, aorta, bladder, and immune cells.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

CHICAGO – Patients who reported using marijuana prior to experiencing an acute MI had significantly lower in-hospital mortality and were less likely to have cardiogenic shock or require an intra-aortic balloon pump than marijuana nonusers with an MI in an eight-state hospital records study, Dr. Cecelia P. Johnson-Sasso reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“If this observation is confirmed in independent studies, further investigation into the possible therapeutic benefit of cannabinoid receptor agonists in acute MI may be warranted,” declared Dr. Johnson-Sasso of the University of Colorado Denver.

She and her coinvestigators obtained hospital records with identity information removed for more than 3 million patients admitted for acute MI during 1994-2013 in eight states: California, Colorado, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Texas, Vermont, and West Virginia.

After excluding concomitant users of cocaine, methamphetamine, or alcohol due to the potential for confounding cardiotoxic effects; MI patients under age 19 because of the likelihood of congenital heart disease; and patients over age 70 because only 0.01% of them admitted to marijuana use, the investigators were left with a study population of 3,854 marijuana users and 1.27 million MI patients who hadn’t used marijuana.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders including baseline comorbid conditions, patient demographics, and payer status, the marijuana users prior to MI had a 17% reduction in in-hospital mortality, were 20% less likely to undergo intra-aortic balloon pump placement, and had a 26% reduction in shock. On the other hand, they were also 19% more likely than marijuana nonusers to be placed on mechanical ventilation. And even though they were equally likely to undergo diagnostic coronary angiography, they were 28% less likely than marijuana nonusers to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention. All of these differences were statistically significant and clinically meaningful.

She was quick to note the limitations of her study: No data were available on readmissions or late mortality, and it’s highly likely that marijuana use by patients with acute MI was significantly underreported during the study period, which was largely before the legalization movement took off.

With state marijuana laws rapidly changing and the legal pot industry becoming a big business, the lack of research into the health consequences of marijuana by disinterested parties has become glaringly obvious, according to Dr. Johnson-Sasso. Cannabinoid receptors are found not only in the brain, but in cardiac muscle, the kidney, liver, vascular and visceral muscle, aorta, bladder, and immune cells.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

CHICAGO – Patients who reported using marijuana prior to experiencing an acute MI had significantly lower in-hospital mortality and were less likely to have cardiogenic shock or require an intra-aortic balloon pump than marijuana nonusers with an MI in an eight-state hospital records study, Dr. Cecelia P. Johnson-Sasso reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“If this observation is confirmed in independent studies, further investigation into the possible therapeutic benefit of cannabinoid receptor agonists in acute MI may be warranted,” declared Dr. Johnson-Sasso of the University of Colorado Denver.

She and her coinvestigators obtained hospital records with identity information removed for more than 3 million patients admitted for acute MI during 1994-2013 in eight states: California, Colorado, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Texas, Vermont, and West Virginia.

After excluding concomitant users of cocaine, methamphetamine, or alcohol due to the potential for confounding cardiotoxic effects; MI patients under age 19 because of the likelihood of congenital heart disease; and patients over age 70 because only 0.01% of them admitted to marijuana use, the investigators were left with a study population of 3,854 marijuana users and 1.27 million MI patients who hadn’t used marijuana.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders including baseline comorbid conditions, patient demographics, and payer status, the marijuana users prior to MI had a 17% reduction in in-hospital mortality, were 20% less likely to undergo intra-aortic balloon pump placement, and had a 26% reduction in shock. On the other hand, they were also 19% more likely than marijuana nonusers to be placed on mechanical ventilation. And even though they were equally likely to undergo diagnostic coronary angiography, they were 28% less likely than marijuana nonusers to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention. All of these differences were statistically significant and clinically meaningful.

She was quick to note the limitations of her study: No data were available on readmissions or late mortality, and it’s highly likely that marijuana use by patients with acute MI was significantly underreported during the study period, which was largely before the legalization movement took off.

With state marijuana laws rapidly changing and the legal pot industry becoming a big business, the lack of research into the health consequences of marijuana by disinterested parties has become glaringly obvious, according to Dr. Johnson-Sasso. Cannabinoid receptors are found not only in the brain, but in cardiac muscle, the kidney, liver, vascular and visceral muscle, aorta, bladder, and immune cells.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

AT ACC 16

Marijuana may lower death risk after acute MI

CHICAGO – Patients who reported using marijuana prior to experiencing an acute MI had significantly lower in-hospital mortality and were less likely to have cardiogenic shock or require an intra-aortic balloon pump than marijuana nonusers with an MI in an eight-state hospital records study, Dr. Cecelia P. Johnson-Sasso reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“If this observation is confirmed in independent studies, further investigation into the possible therapeutic benefit of cannabinoid receptor agonists in acute MI may be warranted,” declared Dr. Johnson-Sasso of the University of Colorado Denver.

She and her coinvestigators obtained hospital records with identity information removed for more than 3 million patients admitted for acute MI during 1994-2013 in eight states: California, Colorado, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Texas, Vermont, and West Virginia.

After excluding concomitant users of cocaine, methamphetamine, or alcohol due to the potential for confounding cardiotoxic effects; MI patients under age 19 because of the likelihood of congenital heart disease; and patients over age 70 because only 0.01% of them admitted to marijuana use, the investigators were left with a study population of 3,854 marijuana users and 1.27 million MI patients who hadn’t used marijuana.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders including baseline comorbid conditions, patient demographics, and payer status, the marijuana users prior to MI had a 17% reduction in in-hospital mortality, were 20% less likely to undergo intra-aortic balloon pump placement, and had a 26% reduction in shock. On the other hand, they were also 19% more likely than marijuana nonusers to be placed on mechanical ventilation. And even though they were equally likely to undergo diagnostic coronary angiography, they were 28% less likely than marijuana nonusers to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention. All of these differences were statistically significant and clinically meaningful.

She was quick to note the limitations of her study: No data were available on readmissions or late mortality, and it’s highly likely that marijuana use by patients with acute MI was significantly underreported during the study period, which was largely before the legalization movement took off.

With state marijuana laws rapidly changing and the legal pot industry becoming a big business, the lack of research into the health consequences of marijuana by disinterested parties has become glaringly obvious, according to Dr. Johnson-Sasso. Cannabinoid receptors are found not only in the brain, but in cardiac muscle, the kidney, liver, vascular and visceral muscle, aorta, bladder, and immune cells.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

CHICAGO – Patients who reported using marijuana prior to experiencing an acute MI had significantly lower in-hospital mortality and were less likely to have cardiogenic shock or require an intra-aortic balloon pump than marijuana nonusers with an MI in an eight-state hospital records study, Dr. Cecelia P. Johnson-Sasso reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“If this observation is confirmed in independent studies, further investigation into the possible therapeutic benefit of cannabinoid receptor agonists in acute MI may be warranted,” declared Dr. Johnson-Sasso of the University of Colorado Denver.

She and her coinvestigators obtained hospital records with identity information removed for more than 3 million patients admitted for acute MI during 1994-2013 in eight states: California, Colorado, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Texas, Vermont, and West Virginia.

After excluding concomitant users of cocaine, methamphetamine, or alcohol due to the potential for confounding cardiotoxic effects; MI patients under age 19 because of the likelihood of congenital heart disease; and patients over age 70 because only 0.01% of them admitted to marijuana use, the investigators were left with a study population of 3,854 marijuana users and 1.27 million MI patients who hadn’t used marijuana.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders including baseline comorbid conditions, patient demographics, and payer status, the marijuana users prior to MI had a 17% reduction in in-hospital mortality, were 20% less likely to undergo intra-aortic balloon pump placement, and had a 26% reduction in shock. On the other hand, they were also 19% more likely than marijuana nonusers to be placed on mechanical ventilation. And even though they were equally likely to undergo diagnostic coronary angiography, they were 28% less likely than marijuana nonusers to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention. All of these differences were statistically significant and clinically meaningful.

She was quick to note the limitations of her study: No data were available on readmissions or late mortality, and it’s highly likely that marijuana use by patients with acute MI was significantly underreported during the study period, which was largely before the legalization movement took off.

With state marijuana laws rapidly changing and the legal pot industry becoming a big business, the lack of research into the health consequences of marijuana by disinterested parties has become glaringly obvious, according to Dr. Johnson-Sasso. Cannabinoid receptors are found not only in the brain, but in cardiac muscle, the kidney, liver, vascular and visceral muscle, aorta, bladder, and immune cells.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

CHICAGO – Patients who reported using marijuana prior to experiencing an acute MI had significantly lower in-hospital mortality and were less likely to have cardiogenic shock or require an intra-aortic balloon pump than marijuana nonusers with an MI in an eight-state hospital records study, Dr. Cecelia P. Johnson-Sasso reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“If this observation is confirmed in independent studies, further investigation into the possible therapeutic benefit of cannabinoid receptor agonists in acute MI may be warranted,” declared Dr. Johnson-Sasso of the University of Colorado Denver.

She and her coinvestigators obtained hospital records with identity information removed for more than 3 million patients admitted for acute MI during 1994-2013 in eight states: California, Colorado, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Texas, Vermont, and West Virginia.

After excluding concomitant users of cocaine, methamphetamine, or alcohol due to the potential for confounding cardiotoxic effects; MI patients under age 19 because of the likelihood of congenital heart disease; and patients over age 70 because only 0.01% of them admitted to marijuana use, the investigators were left with a study population of 3,854 marijuana users and 1.27 million MI patients who hadn’t used marijuana.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders including baseline comorbid conditions, patient demographics, and payer status, the marijuana users prior to MI had a 17% reduction in in-hospital mortality, were 20% less likely to undergo intra-aortic balloon pump placement, and had a 26% reduction in shock. On the other hand, they were also 19% more likely than marijuana nonusers to be placed on mechanical ventilation. And even though they were equally likely to undergo diagnostic coronary angiography, they were 28% less likely than marijuana nonusers to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention. All of these differences were statistically significant and clinically meaningful.

She was quick to note the limitations of her study: No data were available on readmissions or late mortality, and it’s highly likely that marijuana use by patients with acute MI was significantly underreported during the study period, which was largely before the legalization movement took off.

With state marijuana laws rapidly changing and the legal pot industry becoming a big business, the lack of research into the health consequences of marijuana by disinterested parties has become glaringly obvious, according to Dr. Johnson-Sasso. Cannabinoid receptors are found not only in the brain, but in cardiac muscle, the kidney, liver, vascular and visceral muscle, aorta, bladder, and immune cells.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: Patients who used marijuana prior to their acute MI had better outcomes.

Major finding: Marijuana use prior to acute MI was associated with a 17% reduction in in-hospital mortality.

Data source: This was a retrospective analysis of hospital records for nearly 1.3 million MI patients in eight states.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Stroke Risk Rises Quickly in Recent-onset Atrial Fib

CHICAGO – The stroke risk in patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation is similar to that of patients with longer-standing atrial fibrillation, according to a new secondary analysis of the landmark ARISTOTLE trial.

“Our key message is that patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation had a similar risk of stroke but higher mortality than patients with remotely diagnosed atrial fibrillation, suggesting that patients with recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation are not at low risk and therefore warrant stroke prevention strategies,” Dr. Patricia O. Guimaraes said in presenting the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Sometimes we as physicians hesitate in beginning oral anticoagulation therapy for patients that we just diagnosed. And of course patients are often afraid of anticoagulation therapy. But once they present with atrial fibrillation they are already at risk, and that’s why we need to anticoagulate them promptly,” added Dr. Guimaraes of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C.

The benefits of apixaban (Eliquis) over warfarin seen in the overall randomized ARISTOTLE trial (N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:981-92) were preserved in the recent-onset subset of the atrial fibrillation (AF) study population, she noted.

The rationale for this new post hoc analysis of ARISTOTLE is that virtually all of the evidence supporting anticoagulation for stroke prevention in AF is based on studies conducted in patients with permanent, persistent, or long-standing paroxysmal AF. Much less is known about stroke risk and the benefits of anticoagulation in patients with recent-onset AF, Dr. Guimaraes explained.

The 1,899 ARISTOTLE participants with AF onset within 30 days prior to enrollment comprised 10.5% of the total study population, all of whom had AF and at least one other stroke risk factor. The recent-onset subgroup was the same age as the 16,241 subjects in this analysis who had longer-standing AF, but the recent-onset group included a higher proportion of women, had a lower prevalence of CAD, and their cardiovascular risk factor profile differed from that of the remote-onset AF group.

The composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, or all-cause mortality occurred at a rate of 8.69%/year in the recent-onset AF group, compared with 6.43%/year in the remote-onset group. However, in a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the only significant differences in outcome between the two groups were in all-cause mortality – 5.15%/year in the recent-onset group, 3.15% in the remote-onset AF patients – and in the composite of stroke, systemic embolism, or all-cause mortality, which had an incidence of 6.46%/year in the recent-onset group, compared with 4.57%/year in remote-onset patients.

Turning to the impact of apixaban, Dr. Guimaraes noted that, as previously reported in the overall study, the primary endpoint of stroke or systemic embolism occurred in the apixaban group at a rate of 1.27%/year, compared with 1.6%/year with warfarin, for a 21% relative risk reduction in favor of the newer agent. She and her coinvestigators determined that in the remote-onset AF subgroup the relative risk reduction was 20%, while in the recent-onset subgroup the size of the effect was similar at 22%.

The composite safety endpoint of major or clinically relevant bleeding occurred in the remote-onset patients at a rate of 3.97%/year with apixaban versus 5.97%/year with warfarin, for a 33% relative risk reduction favoring the novel agent. In the recent-onset group, the rates were 5.04%/year with apixaban, compared with 6.4%/year with warfarin, for a 22% relative risk reduction.

Dr. Guimaraes observed an important limitation of this post hoc analysis is that the remote-onset AF group may have been selected for improved survival, since they didn’t die in the first 30 days after diagnosis.

Session co-chair Dr. Brian Olshansky commented that this analysis, which highlights the risks of recent-onset AF, argues for a strategy whereby a patient who presents to the ED with new-onset AF should get sent home on apixaban rather than being hospitalized for several days in order to be stabilized on warfarin.

“With recent-onset atrial fibrillation it’s going to take you several days to get anticoagulated with warfarin, whereas you’re immediately anticoagulated with apixaban,” said Dr. Olshansky, emeritus professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The ARISTOTLE trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Guimaraes reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – The stroke risk in patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation is similar to that of patients with longer-standing atrial fibrillation, according to a new secondary analysis of the landmark ARISTOTLE trial.

“Our key message is that patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation had a similar risk of stroke but higher mortality than patients with remotely diagnosed atrial fibrillation, suggesting that patients with recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation are not at low risk and therefore warrant stroke prevention strategies,” Dr. Patricia O. Guimaraes said in presenting the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Sometimes we as physicians hesitate in beginning oral anticoagulation therapy for patients that we just diagnosed. And of course patients are often afraid of anticoagulation therapy. But once they present with atrial fibrillation they are already at risk, and that’s why we need to anticoagulate them promptly,” added Dr. Guimaraes of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C.

The benefits of apixaban (Eliquis) over warfarin seen in the overall randomized ARISTOTLE trial (N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:981-92) were preserved in the recent-onset subset of the atrial fibrillation (AF) study population, she noted.

The rationale for this new post hoc analysis of ARISTOTLE is that virtually all of the evidence supporting anticoagulation for stroke prevention in AF is based on studies conducted in patients with permanent, persistent, or long-standing paroxysmal AF. Much less is known about stroke risk and the benefits of anticoagulation in patients with recent-onset AF, Dr. Guimaraes explained.

The 1,899 ARISTOTLE participants with AF onset within 30 days prior to enrollment comprised 10.5% of the total study population, all of whom had AF and at least one other stroke risk factor. The recent-onset subgroup was the same age as the 16,241 subjects in this analysis who had longer-standing AF, but the recent-onset group included a higher proportion of women, had a lower prevalence of CAD, and their cardiovascular risk factor profile differed from that of the remote-onset AF group.

The composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, or all-cause mortality occurred at a rate of 8.69%/year in the recent-onset AF group, compared with 6.43%/year in the remote-onset group. However, in a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the only significant differences in outcome between the two groups were in all-cause mortality – 5.15%/year in the recent-onset group, 3.15% in the remote-onset AF patients – and in the composite of stroke, systemic embolism, or all-cause mortality, which had an incidence of 6.46%/year in the recent-onset group, compared with 4.57%/year in remote-onset patients.

Turning to the impact of apixaban, Dr. Guimaraes noted that, as previously reported in the overall study, the primary endpoint of stroke or systemic embolism occurred in the apixaban group at a rate of 1.27%/year, compared with 1.6%/year with warfarin, for a 21% relative risk reduction in favor of the newer agent. She and her coinvestigators determined that in the remote-onset AF subgroup the relative risk reduction was 20%, while in the recent-onset subgroup the size of the effect was similar at 22%.

The composite safety endpoint of major or clinically relevant bleeding occurred in the remote-onset patients at a rate of 3.97%/year with apixaban versus 5.97%/year with warfarin, for a 33% relative risk reduction favoring the novel agent. In the recent-onset group, the rates were 5.04%/year with apixaban, compared with 6.4%/year with warfarin, for a 22% relative risk reduction.

Dr. Guimaraes observed an important limitation of this post hoc analysis is that the remote-onset AF group may have been selected for improved survival, since they didn’t die in the first 30 days after diagnosis.

Session co-chair Dr. Brian Olshansky commented that this analysis, which highlights the risks of recent-onset AF, argues for a strategy whereby a patient who presents to the ED with new-onset AF should get sent home on apixaban rather than being hospitalized for several days in order to be stabilized on warfarin.

“With recent-onset atrial fibrillation it’s going to take you several days to get anticoagulated with warfarin, whereas you’re immediately anticoagulated with apixaban,” said Dr. Olshansky, emeritus professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The ARISTOTLE trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Guimaraes reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – The stroke risk in patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation is similar to that of patients with longer-standing atrial fibrillation, according to a new secondary analysis of the landmark ARISTOTLE trial.

“Our key message is that patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation had a similar risk of stroke but higher mortality than patients with remotely diagnosed atrial fibrillation, suggesting that patients with recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation are not at low risk and therefore warrant stroke prevention strategies,” Dr. Patricia O. Guimaraes said in presenting the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Sometimes we as physicians hesitate in beginning oral anticoagulation therapy for patients that we just diagnosed. And of course patients are often afraid of anticoagulation therapy. But once they present with atrial fibrillation they are already at risk, and that’s why we need to anticoagulate them promptly,” added Dr. Guimaraes of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C.

The benefits of apixaban (Eliquis) over warfarin seen in the overall randomized ARISTOTLE trial (N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:981-92) were preserved in the recent-onset subset of the atrial fibrillation (AF) study population, she noted.

The rationale for this new post hoc analysis of ARISTOTLE is that virtually all of the evidence supporting anticoagulation for stroke prevention in AF is based on studies conducted in patients with permanent, persistent, or long-standing paroxysmal AF. Much less is known about stroke risk and the benefits of anticoagulation in patients with recent-onset AF, Dr. Guimaraes explained.

The 1,899 ARISTOTLE participants with AF onset within 30 days prior to enrollment comprised 10.5% of the total study population, all of whom had AF and at least one other stroke risk factor. The recent-onset subgroup was the same age as the 16,241 subjects in this analysis who had longer-standing AF, but the recent-onset group included a higher proportion of women, had a lower prevalence of CAD, and their cardiovascular risk factor profile differed from that of the remote-onset AF group.

The composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, or all-cause mortality occurred at a rate of 8.69%/year in the recent-onset AF group, compared with 6.43%/year in the remote-onset group. However, in a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the only significant differences in outcome between the two groups were in all-cause mortality – 5.15%/year in the recent-onset group, 3.15% in the remote-onset AF patients – and in the composite of stroke, systemic embolism, or all-cause mortality, which had an incidence of 6.46%/year in the recent-onset group, compared with 4.57%/year in remote-onset patients.

Turning to the impact of apixaban, Dr. Guimaraes noted that, as previously reported in the overall study, the primary endpoint of stroke or systemic embolism occurred in the apixaban group at a rate of 1.27%/year, compared with 1.6%/year with warfarin, for a 21% relative risk reduction in favor of the newer agent. She and her coinvestigators determined that in the remote-onset AF subgroup the relative risk reduction was 20%, while in the recent-onset subgroup the size of the effect was similar at 22%.

The composite safety endpoint of major or clinically relevant bleeding occurred in the remote-onset patients at a rate of 3.97%/year with apixaban versus 5.97%/year with warfarin, for a 33% relative risk reduction favoring the novel agent. In the recent-onset group, the rates were 5.04%/year with apixaban, compared with 6.4%/year with warfarin, for a 22% relative risk reduction.

Dr. Guimaraes observed an important limitation of this post hoc analysis is that the remote-onset AF group may have been selected for improved survival, since they didn’t die in the first 30 days after diagnosis.

Session co-chair Dr. Brian Olshansky commented that this analysis, which highlights the risks of recent-onset AF, argues for a strategy whereby a patient who presents to the ED with new-onset AF should get sent home on apixaban rather than being hospitalized for several days in order to be stabilized on warfarin.

“With recent-onset atrial fibrillation it’s going to take you several days to get anticoagulated with warfarin, whereas you’re immediately anticoagulated with apixaban,” said Dr. Olshansky, emeritus professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The ARISTOTLE trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Guimaraes reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT ACC 16

Stroke risk rises quickly in recent-onset atrial fib

CHICAGO – The stroke risk in patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation is similar to that of patients with longer-standing atrial fibrillation, according to a new secondary analysis of the landmark ARISTOTLE trial.

“Our key message is that patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation had a similar risk of stroke but higher mortality than patients with remotely diagnosed atrial fibrillation, suggesting that patients with recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation are not at low risk and therefore warrant stroke prevention strategies,” Dr. Patricia O. Guimaraes said in presenting the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Sometimes we as physicians hesitate in beginning oral anticoagulation therapy for patients that we just diagnosed. And of course patients are often afraid of anticoagulation therapy. But once they present with atrial fibrillation they are already at risk, and that’s why we need to anticoagulate them promptly,” added Dr. Guimaraes of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C.

The benefits of apixaban (Eliquis) over warfarin seen in the overall randomized ARISTOTLE trial (N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:981-92) were preserved in the recent-onset subset of the atrial fibrillation (AF) study population, she noted.

The rationale for this new post hoc analysis of ARISTOTLE is that virtually all of the evidence supporting anticoagulation for stroke prevention in AF is based on studies conducted in patients with permanent, persistent, or long-standing paroxysmal AF. Much less is known about stroke risk and the benefits of anticoagulation in patients with recent-onset AF, Dr. Guimaraes explained.

The 1,899 ARISTOTLE participants with AF onset within 30 days prior to enrollment comprised 10.5% of the total study population, all of whom had AF and at least one other stroke risk factor. The recent-onset subgroup was the same age as the 16,241 subjects in this analysis who had longer-standing AF, but the recent-onset group included a higher proportion of women, had a lower prevalence of CAD, and their cardiovascular risk factor profile differed from that of the remote-onset AF group.

The composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, or all-cause mortality occurred at a rate of 8.69%/year in the recent-onset AF group, compared with 6.43%/year in the remote-onset group. However, in a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the only significant differences in outcome between the two groups were in all-cause mortality – 5.15%/year in the recent-onset group, 3.15% in the remote-onset AF patients – and in the composite of stroke, systemic embolism, or all-cause mortality, which had an incidence of 6.46%/year in the recent-onset group, compared with 4.57%/year in remote-onset patients.

Turning to the impact of apixaban, Dr. Guimaraes noted that, as previously reported in the overall study, the primary endpoint of stroke or systemic embolism occurred in the apixaban group at a rate of 1.27%/year, compared with 1.6%/year with warfarin, for a 21% relative risk reduction in favor of the newer agent. She and her coinvestigators determined that in the remote-onset AF subgroup the relative risk reduction was 20%, while in the recent-onset subgroup the size of the effect was similar at 22%.

The composite safety endpoint of major or clinically relevant bleeding occurred in the remote-onset patients at a rate of 3.97%/year with apixaban versus 5.97%/year with warfarin, for a 33% relative risk reduction favoring the novel agent. In the recent-onset group, the rates were 5.04%/year with apixaban, compared with 6.4%/year with warfarin, for a 22% relative risk reduction.

Dr. Guimaraes observed an important limitation of this post hoc analysis is that the remote-onset AF group may have been selected for improved survival, since they didn’t die in the first 30 days after diagnosis.

Session co-chair Dr. Brian Olshansky commented that this analysis, which highlights the risks of recent-onset AF, argues for a strategy whereby a patient who presents to the ED with new-onset AF should get sent home on apixaban rather than being hospitalized for several days in order to be stabilized on warfarin.

“With recent-onset atrial fibrillation it’s going to take you several days to get anticoagulated with warfarin, whereas you’re immediately anticoagulated with apixaban,” said Dr. Olshansky, emeritus professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The ARISTOTLE trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Guimaraes reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – The stroke risk in patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation is similar to that of patients with longer-standing atrial fibrillation, according to a new secondary analysis of the landmark ARISTOTLE trial.

“Our key message is that patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation had a similar risk of stroke but higher mortality than patients with remotely diagnosed atrial fibrillation, suggesting that patients with recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation are not at low risk and therefore warrant stroke prevention strategies,” Dr. Patricia O. Guimaraes said in presenting the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Sometimes we as physicians hesitate in beginning oral anticoagulation therapy for patients that we just diagnosed. And of course patients are often afraid of anticoagulation therapy. But once they present with atrial fibrillation they are already at risk, and that’s why we need to anticoagulate them promptly,” added Dr. Guimaraes of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C.

The benefits of apixaban (Eliquis) over warfarin seen in the overall randomized ARISTOTLE trial (N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:981-92) were preserved in the recent-onset subset of the atrial fibrillation (AF) study population, she noted.

The rationale for this new post hoc analysis of ARISTOTLE is that virtually all of the evidence supporting anticoagulation for stroke prevention in AF is based on studies conducted in patients with permanent, persistent, or long-standing paroxysmal AF. Much less is known about stroke risk and the benefits of anticoagulation in patients with recent-onset AF, Dr. Guimaraes explained.

The 1,899 ARISTOTLE participants with AF onset within 30 days prior to enrollment comprised 10.5% of the total study population, all of whom had AF and at least one other stroke risk factor. The recent-onset subgroup was the same age as the 16,241 subjects in this analysis who had longer-standing AF, but the recent-onset group included a higher proportion of women, had a lower prevalence of CAD, and their cardiovascular risk factor profile differed from that of the remote-onset AF group.

The composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, or all-cause mortality occurred at a rate of 8.69%/year in the recent-onset AF group, compared with 6.43%/year in the remote-onset group. However, in a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the only significant differences in outcome between the two groups were in all-cause mortality – 5.15%/year in the recent-onset group, 3.15% in the remote-onset AF patients – and in the composite of stroke, systemic embolism, or all-cause mortality, which had an incidence of 6.46%/year in the recent-onset group, compared with 4.57%/year in remote-onset patients.

Turning to the impact of apixaban, Dr. Guimaraes noted that, as previously reported in the overall study, the primary endpoint of stroke or systemic embolism occurred in the apixaban group at a rate of 1.27%/year, compared with 1.6%/year with warfarin, for a 21% relative risk reduction in favor of the newer agent. She and her coinvestigators determined that in the remote-onset AF subgroup the relative risk reduction was 20%, while in the recent-onset subgroup the size of the effect was similar at 22%.

The composite safety endpoint of major or clinically relevant bleeding occurred in the remote-onset patients at a rate of 3.97%/year with apixaban versus 5.97%/year with warfarin, for a 33% relative risk reduction favoring the novel agent. In the recent-onset group, the rates were 5.04%/year with apixaban, compared with 6.4%/year with warfarin, for a 22% relative risk reduction.

Dr. Guimaraes observed an important limitation of this post hoc analysis is that the remote-onset AF group may have been selected for improved survival, since they didn’t die in the first 30 days after diagnosis.

Session co-chair Dr. Brian Olshansky commented that this analysis, which highlights the risks of recent-onset AF, argues for a strategy whereby a patient who presents to the ED with new-onset AF should get sent home on apixaban rather than being hospitalized for several days in order to be stabilized on warfarin.

“With recent-onset atrial fibrillation it’s going to take you several days to get anticoagulated with warfarin, whereas you’re immediately anticoagulated with apixaban,” said Dr. Olshansky, emeritus professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The ARISTOTLE trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Guimaraes reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – The stroke risk in patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation is similar to that of patients with longer-standing atrial fibrillation, according to a new secondary analysis of the landmark ARISTOTLE trial.

“Our key message is that patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation had a similar risk of stroke but higher mortality than patients with remotely diagnosed atrial fibrillation, suggesting that patients with recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation are not at low risk and therefore warrant stroke prevention strategies,” Dr. Patricia O. Guimaraes said in presenting the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Sometimes we as physicians hesitate in beginning oral anticoagulation therapy for patients that we just diagnosed. And of course patients are often afraid of anticoagulation therapy. But once they present with atrial fibrillation they are already at risk, and that’s why we need to anticoagulate them promptly,” added Dr. Guimaraes of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C.

The benefits of apixaban (Eliquis) over warfarin seen in the overall randomized ARISTOTLE trial (N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:981-92) were preserved in the recent-onset subset of the atrial fibrillation (AF) study population, she noted.

The rationale for this new post hoc analysis of ARISTOTLE is that virtually all of the evidence supporting anticoagulation for stroke prevention in AF is based on studies conducted in patients with permanent, persistent, or long-standing paroxysmal AF. Much less is known about stroke risk and the benefits of anticoagulation in patients with recent-onset AF, Dr. Guimaraes explained.

The 1,899 ARISTOTLE participants with AF onset within 30 days prior to enrollment comprised 10.5% of the total study population, all of whom had AF and at least one other stroke risk factor. The recent-onset subgroup was the same age as the 16,241 subjects in this analysis who had longer-standing AF, but the recent-onset group included a higher proportion of women, had a lower prevalence of CAD, and their cardiovascular risk factor profile differed from that of the remote-onset AF group.

The composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, or all-cause mortality occurred at a rate of 8.69%/year in the recent-onset AF group, compared with 6.43%/year in the remote-onset group. However, in a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the only significant differences in outcome between the two groups were in all-cause mortality – 5.15%/year in the recent-onset group, 3.15% in the remote-onset AF patients – and in the composite of stroke, systemic embolism, or all-cause mortality, which had an incidence of 6.46%/year in the recent-onset group, compared with 4.57%/year in remote-onset patients.

Turning to the impact of apixaban, Dr. Guimaraes noted that, as previously reported in the overall study, the primary endpoint of stroke or systemic embolism occurred in the apixaban group at a rate of 1.27%/year, compared with 1.6%/year with warfarin, for a 21% relative risk reduction in favor of the newer agent. She and her coinvestigators determined that in the remote-onset AF subgroup the relative risk reduction was 20%, while in the recent-onset subgroup the size of the effect was similar at 22%.

The composite safety endpoint of major or clinically relevant bleeding occurred in the remote-onset patients at a rate of 3.97%/year with apixaban versus 5.97%/year with warfarin, for a 33% relative risk reduction favoring the novel agent. In the recent-onset group, the rates were 5.04%/year with apixaban, compared with 6.4%/year with warfarin, for a 22% relative risk reduction.

Dr. Guimaraes observed an important limitation of this post hoc analysis is that the remote-onset AF group may have been selected for improved survival, since they didn’t die in the first 30 days after diagnosis.

Session co-chair Dr. Brian Olshansky commented that this analysis, which highlights the risks of recent-onset AF, argues for a strategy whereby a patient who presents to the ED with new-onset AF should get sent home on apixaban rather than being hospitalized for several days in order to be stabilized on warfarin.

“With recent-onset atrial fibrillation it’s going to take you several days to get anticoagulated with warfarin, whereas you’re immediately anticoagulated with apixaban,” said Dr. Olshansky, emeritus professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

The ARISTOTLE trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Guimaraes reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Don’t delay starting oral anticoagulation in patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation.

Major finding: All-cause mortality occurred at a rate of 5.15%/year in patients started on apixaban or warfarin within 30 days following diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, compared with 3.15%/year in those with longer-duration atrial fibrillation.

Data source: This was a secondary post hoc analysis of 18,140 participants in the randomized, double-blind, prospective ARISTOTLE trial of apixaban versus warfarin for stroke prevention.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Rhythm control may be best for atrial fib in HFpEF

CHICAGO – Atrial fibrillation with good heart rate control in patients who have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is independently associated with exercise intolerance, impaired contractile reserve, and a sharply higher mortality rate than in matched HFpEF patients without the arrhythmia, a retrospective analysis showed.

“Our study, the largest of its kind, provides mechanistic evidence from cardiopulmonary testing that a rhythm control strategy may potentially improve peak exercise capacity and survival in this patient population, a finding that of course requires future prospective appraisal in randomized trials comparing rate and rhythm control of atrial fibrillation in HFpEF,” Dr. Mohamed Badreldin Elshazly reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In the meantime, his study also shows the useful role cardiopulmonary stress testing can play in the setting of atrial fibrillation (AF) in HFpEF, he added.

“Cardiopulmonary stress tests are cheap and easy to do. They’re a big asset for personalized medicine. Using an objective measure like cardiopulmonary stress testing to define the physiologic and hemodynamic consequences of atrial fibrillation in individual patients may help identify those in whom rhythm control may improve exercise tolerance and quality of life, and those who may be okay with rate control,” according to Dr. Elshazly of the Cleveland Clinic.

He noted that while it’s well established that atrial fibrillation is associated with exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and that restoration of sinus rhythm in such patients has a positive impact on exercise hemodynamics, symptom severity, and quality of life, the situation is murkier regarding AF in patients with HFpEF. Prior studies were generally small and unable to establish whether AF was independently associated with exercise intolerance or if HFpEF patients who developed AF were sicker and higher risk.

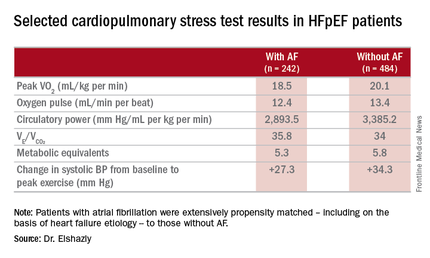

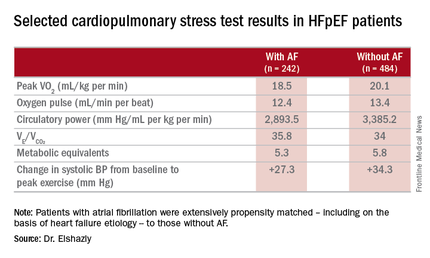

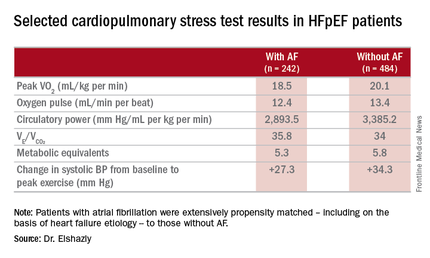

He presented a retrospective, case-control study in a cohort of 1,825 patients with HFpEF referred for maximal, symptom-limited cardiopulmonary stress testing at the Cleveland Clinic. Among these were 242 patients with AF. They were extensively propensity matched – including on the basis of heart failure etiology – to 484 HFpEF patients without AF.

“That’s what makes our study strong. We were the first to be able to do propensity matching and therefore account for other risk factors in our analysis,” Dr. Elshazly explained.

The investigators measured peak oxygen uptake (VO2), the minute ventilation–carbon dioxide production relationship (VE/VCO2) as an indicator of ventilatory efficiency, metabolic equivalents (METS), ventilatory anaerobic threshold, circulatory power as a proxy for cardiac power, peak oxygen pulse as a surrogate for stroke volume, and resting and peak heart rate and systolic blood pressure. The patients with AF were in fibrillation at the time of their cardiopulmonary stress testing.

The HFpEF patients with AF had a mean resting heart rate of 70 beats per minute and a peak rate of 130 bpm. This group showed evidence of impaired peak exercise tolerance as reflected in lower peak VO2, oxygen pulse, and circulatory power at peak exercise. Their VE/VCO2 was higher, indicating impaired ventilatory efficiency. Notably, however, their submaximal exercise capacity was similar to the non-AF controls.

“Atrial fibrillation in these patients is really more of a disease that shows itself in patients when you take them to their peak exercise capacity,” he observed.

All-cause mortality was significantly higher in the AF as compared with no-AF patients with HFpEF. The mortality curves separated early and the divergence grew larger over the course of 8 years of follow-up.

One audience member pointed out that the large mortality difference between the two groups seems disproportionate to the rather modest differences in exercise capacity.

“It brings up an interesting point,” Dr. Elshazly replied. “Maybe the increase in total mortality that we see is being driven by other things besides cardiovascular mortality. Our data doesn’t capture the specific cause of death, be it cancer, for example, but it does raise the idea that this mortality difference is not all driven by cardiovascular mortality, but by atrial fibrillation.”

Dr. Elshazly reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his institutionally supported study.

CHICAGO – Atrial fibrillation with good heart rate control in patients who have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is independently associated with exercise intolerance, impaired contractile reserve, and a sharply higher mortality rate than in matched HFpEF patients without the arrhythmia, a retrospective analysis showed.

“Our study, the largest of its kind, provides mechanistic evidence from cardiopulmonary testing that a rhythm control strategy may potentially improve peak exercise capacity and survival in this patient population, a finding that of course requires future prospective appraisal in randomized trials comparing rate and rhythm control of atrial fibrillation in HFpEF,” Dr. Mohamed Badreldin Elshazly reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In the meantime, his study also shows the useful role cardiopulmonary stress testing can play in the setting of atrial fibrillation (AF) in HFpEF, he added.

“Cardiopulmonary stress tests are cheap and easy to do. They’re a big asset for personalized medicine. Using an objective measure like cardiopulmonary stress testing to define the physiologic and hemodynamic consequences of atrial fibrillation in individual patients may help identify those in whom rhythm control may improve exercise tolerance and quality of life, and those who may be okay with rate control,” according to Dr. Elshazly of the Cleveland Clinic.

He noted that while it’s well established that atrial fibrillation is associated with exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and that restoration of sinus rhythm in such patients has a positive impact on exercise hemodynamics, symptom severity, and quality of life, the situation is murkier regarding AF in patients with HFpEF. Prior studies were generally small and unable to establish whether AF was independently associated with exercise intolerance or if HFpEF patients who developed AF were sicker and higher risk.

He presented a retrospective, case-control study in a cohort of 1,825 patients with HFpEF referred for maximal, symptom-limited cardiopulmonary stress testing at the Cleveland Clinic. Among these were 242 patients with AF. They were extensively propensity matched – including on the basis of heart failure etiology – to 484 HFpEF patients without AF.

“That’s what makes our study strong. We were the first to be able to do propensity matching and therefore account for other risk factors in our analysis,” Dr. Elshazly explained.

The investigators measured peak oxygen uptake (VO2), the minute ventilation–carbon dioxide production relationship (VE/VCO2) as an indicator of ventilatory efficiency, metabolic equivalents (METS), ventilatory anaerobic threshold, circulatory power as a proxy for cardiac power, peak oxygen pulse as a surrogate for stroke volume, and resting and peak heart rate and systolic blood pressure. The patients with AF were in fibrillation at the time of their cardiopulmonary stress testing.

The HFpEF patients with AF had a mean resting heart rate of 70 beats per minute and a peak rate of 130 bpm. This group showed evidence of impaired peak exercise tolerance as reflected in lower peak VO2, oxygen pulse, and circulatory power at peak exercise. Their VE/VCO2 was higher, indicating impaired ventilatory efficiency. Notably, however, their submaximal exercise capacity was similar to the non-AF controls.

“Atrial fibrillation in these patients is really more of a disease that shows itself in patients when you take them to their peak exercise capacity,” he observed.

All-cause mortality was significantly higher in the AF as compared with no-AF patients with HFpEF. The mortality curves separated early and the divergence grew larger over the course of 8 years of follow-up.

One audience member pointed out that the large mortality difference between the two groups seems disproportionate to the rather modest differences in exercise capacity.

“It brings up an interesting point,” Dr. Elshazly replied. “Maybe the increase in total mortality that we see is being driven by other things besides cardiovascular mortality. Our data doesn’t capture the specific cause of death, be it cancer, for example, but it does raise the idea that this mortality difference is not all driven by cardiovascular mortality, but by atrial fibrillation.”

Dr. Elshazly reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his institutionally supported study.

CHICAGO – Atrial fibrillation with good heart rate control in patients who have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is independently associated with exercise intolerance, impaired contractile reserve, and a sharply higher mortality rate than in matched HFpEF patients without the arrhythmia, a retrospective analysis showed.

“Our study, the largest of its kind, provides mechanistic evidence from cardiopulmonary testing that a rhythm control strategy may potentially improve peak exercise capacity and survival in this patient population, a finding that of course requires future prospective appraisal in randomized trials comparing rate and rhythm control of atrial fibrillation in HFpEF,” Dr. Mohamed Badreldin Elshazly reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In the meantime, his study also shows the useful role cardiopulmonary stress testing can play in the setting of atrial fibrillation (AF) in HFpEF, he added.

“Cardiopulmonary stress tests are cheap and easy to do. They’re a big asset for personalized medicine. Using an objective measure like cardiopulmonary stress testing to define the physiologic and hemodynamic consequences of atrial fibrillation in individual patients may help identify those in whom rhythm control may improve exercise tolerance and quality of life, and those who may be okay with rate control,” according to Dr. Elshazly of the Cleveland Clinic.

He noted that while it’s well established that atrial fibrillation is associated with exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and that restoration of sinus rhythm in such patients has a positive impact on exercise hemodynamics, symptom severity, and quality of life, the situation is murkier regarding AF in patients with HFpEF. Prior studies were generally small and unable to establish whether AF was independently associated with exercise intolerance or if HFpEF patients who developed AF were sicker and higher risk.

He presented a retrospective, case-control study in a cohort of 1,825 patients with HFpEF referred for maximal, symptom-limited cardiopulmonary stress testing at the Cleveland Clinic. Among these were 242 patients with AF. They were extensively propensity matched – including on the basis of heart failure etiology – to 484 HFpEF patients without AF.

“That’s what makes our study strong. We were the first to be able to do propensity matching and therefore account for other risk factors in our analysis,” Dr. Elshazly explained.

The investigators measured peak oxygen uptake (VO2), the minute ventilation–carbon dioxide production relationship (VE/VCO2) as an indicator of ventilatory efficiency, metabolic equivalents (METS), ventilatory anaerobic threshold, circulatory power as a proxy for cardiac power, peak oxygen pulse as a surrogate for stroke volume, and resting and peak heart rate and systolic blood pressure. The patients with AF were in fibrillation at the time of their cardiopulmonary stress testing.

The HFpEF patients with AF had a mean resting heart rate of 70 beats per minute and a peak rate of 130 bpm. This group showed evidence of impaired peak exercise tolerance as reflected in lower peak VO2, oxygen pulse, and circulatory power at peak exercise. Their VE/VCO2 was higher, indicating impaired ventilatory efficiency. Notably, however, their submaximal exercise capacity was similar to the non-AF controls.

“Atrial fibrillation in these patients is really more of a disease that shows itself in patients when you take them to their peak exercise capacity,” he observed.

All-cause mortality was significantly higher in the AF as compared with no-AF patients with HFpEF. The mortality curves separated early and the divergence grew larger over the course of 8 years of follow-up.

One audience member pointed out that the large mortality difference between the two groups seems disproportionate to the rather modest differences in exercise capacity.

“It brings up an interesting point,” Dr. Elshazly replied. “Maybe the increase in total mortality that we see is being driven by other things besides cardiovascular mortality. Our data doesn’t capture the specific cause of death, be it cancer, for example, but it does raise the idea that this mortality difference is not all driven by cardiovascular mortality, but by atrial fibrillation.”

Dr. Elshazly reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his institutionally supported study.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: Atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is associated with exercise intolerance and increased mortality.

Major finding: Mean peak VO2 was 18.5 mL/kg per minute in patients with HFpEF and atrial fibrillation, significantly less than the 20.1 mL/kg per minute in controls.

Data source: A retrospective, single-institution study of cardiopulmonary stress test findings and 8-year mortality in 242 patients with HFpEF and atrial fibrillation and 484 propensity-matched controls with HFpEF and no arrhythmia.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his institutionally supported study.

Prompt antidepressant treatment swiftly chops cardiovascular risk

CHICAGO – Prompt, effective treatment for depression in the primary care setting appears to swiftly reduce the elevated cardiovascular risk known to be tied to the mood disorder, Heidi Thomas May, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“We know that depression is a risk factor for long-term adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Our study shows that it can also have immediate effects on someone’s cardiovascular health. I think our study highlights the importance of screening for depression in the primary care setting – and if someone’s depressed, they need to be treated,” said Dr. May, a cardiovascular and genetic epidemiologist at Intermountain Medical Center in Murray, Utah.

She presented an observational study of the electronic medical records of 7,559 Intermountain Healthcare patients over age 40 years who completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression screening tool during a visit to an Intermountain primary care clinic for any reason. They completed another PHQ-9 a median of 2.7 years later. Under the Intermountain system, a PHQ-9 score of 10 or more triggers implementation of a depression treatment pathway, the specifics of which vary depending upon the severity of symptoms.

On the basis of their two PHQ-9 scores, all patients were classified into one of four groups: The “nondepressed” group of 3,286 patients had a score of 9 or less on both occasions; the “remained depressed” cohort of 1,987 patients scored 10 or more on both PHQ-9s; the “no longer depressed” group of 1,542 patients scored at least 10 but subsequently improved by at least 5 points to a score of 9 or less; and the 735 patients in the “became depressed” group first scored 9 or less on the PHQ-9 but subsequently had at least a 5-point increase to a score of 10 or more.

The subjects were then followed for major adverse cardiovascular events, or MACE – defined as a composite of death, diagnosis of coronary artery disease, acute MI, stroke, and heart failure hospitalization – for a median of 208 days after completing their second PHQ-9.

The MACE rate was 4.8% in the nondepressed group and similar at 4.6% in the “no longer depressed” group, Dr. May reported. Both groups fared significantly better than the “remained depressed” and “became depressed” groups, which had MACE rates of 6% and 6.4%, respectively.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, prior disease diagnoses, medications, and other potential confounders, the “remained depressed” group was 33% more likely to experience a cardiovascular event than was the nondepressed group, she said. The “became depressed” group had a 44% increase in risk, compared with the nondepressed individuals. In contrast, the MACE risk in patients in the “no longer depressed” group was not significantly different from that of patients who weren’t depressed at either time point. And the MACE risk of patients who became depressed during the course of the study was no different from that of patients who remained depressed at both time points.

This is the first study of its kind, Dr. May said. Hence, the results require confirmation, ideally in a randomized clinical trial.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by Intermountain Healthcare.

CHICAGO – Prompt, effective treatment for depression in the primary care setting appears to swiftly reduce the elevated cardiovascular risk known to be tied to the mood disorder, Heidi Thomas May, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“We know that depression is a risk factor for long-term adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Our study shows that it can also have immediate effects on someone’s cardiovascular health. I think our study highlights the importance of screening for depression in the primary care setting – and if someone’s depressed, they need to be treated,” said Dr. May, a cardiovascular and genetic epidemiologist at Intermountain Medical Center in Murray, Utah.

She presented an observational study of the electronic medical records of 7,559 Intermountain Healthcare patients over age 40 years who completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression screening tool during a visit to an Intermountain primary care clinic for any reason. They completed another PHQ-9 a median of 2.7 years later. Under the Intermountain system, a PHQ-9 score of 10 or more triggers implementation of a depression treatment pathway, the specifics of which vary depending upon the severity of symptoms.

On the basis of their two PHQ-9 scores, all patients were classified into one of four groups: The “nondepressed” group of 3,286 patients had a score of 9 or less on both occasions; the “remained depressed” cohort of 1,987 patients scored 10 or more on both PHQ-9s; the “no longer depressed” group of 1,542 patients scored at least 10 but subsequently improved by at least 5 points to a score of 9 or less; and the 735 patients in the “became depressed” group first scored 9 or less on the PHQ-9 but subsequently had at least a 5-point increase to a score of 10 or more.

The subjects were then followed for major adverse cardiovascular events, or MACE – defined as a composite of death, diagnosis of coronary artery disease, acute MI, stroke, and heart failure hospitalization – for a median of 208 days after completing their second PHQ-9.

The MACE rate was 4.8% in the nondepressed group and similar at 4.6% in the “no longer depressed” group, Dr. May reported. Both groups fared significantly better than the “remained depressed” and “became depressed” groups, which had MACE rates of 6% and 6.4%, respectively.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, prior disease diagnoses, medications, and other potential confounders, the “remained depressed” group was 33% more likely to experience a cardiovascular event than was the nondepressed group, she said. The “became depressed” group had a 44% increase in risk, compared with the nondepressed individuals. In contrast, the MACE risk in patients in the “no longer depressed” group was not significantly different from that of patients who weren’t depressed at either time point. And the MACE risk of patients who became depressed during the course of the study was no different from that of patients who remained depressed at both time points.

This is the first study of its kind, Dr. May said. Hence, the results require confirmation, ideally in a randomized clinical trial.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by Intermountain Healthcare.

CHICAGO – Prompt, effective treatment for depression in the primary care setting appears to swiftly reduce the elevated cardiovascular risk known to be tied to the mood disorder, Heidi Thomas May, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“We know that depression is a risk factor for long-term adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Our study shows that it can also have immediate effects on someone’s cardiovascular health. I think our study highlights the importance of screening for depression in the primary care setting – and if someone’s depressed, they need to be treated,” said Dr. May, a cardiovascular and genetic epidemiologist at Intermountain Medical Center in Murray, Utah.

She presented an observational study of the electronic medical records of 7,559 Intermountain Healthcare patients over age 40 years who completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression screening tool during a visit to an Intermountain primary care clinic for any reason. They completed another PHQ-9 a median of 2.7 years later. Under the Intermountain system, a PHQ-9 score of 10 or more triggers implementation of a depression treatment pathway, the specifics of which vary depending upon the severity of symptoms.

On the basis of their two PHQ-9 scores, all patients were classified into one of four groups: The “nondepressed” group of 3,286 patients had a score of 9 or less on both occasions; the “remained depressed” cohort of 1,987 patients scored 10 or more on both PHQ-9s; the “no longer depressed” group of 1,542 patients scored at least 10 but subsequently improved by at least 5 points to a score of 9 or less; and the 735 patients in the “became depressed” group first scored 9 or less on the PHQ-9 but subsequently had at least a 5-point increase to a score of 10 or more.

The subjects were then followed for major adverse cardiovascular events, or MACE – defined as a composite of death, diagnosis of coronary artery disease, acute MI, stroke, and heart failure hospitalization – for a median of 208 days after completing their second PHQ-9.

The MACE rate was 4.8% in the nondepressed group and similar at 4.6% in the “no longer depressed” group, Dr. May reported. Both groups fared significantly better than the “remained depressed” and “became depressed” groups, which had MACE rates of 6% and 6.4%, respectively.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, prior disease diagnoses, medications, and other potential confounders, the “remained depressed” group was 33% more likely to experience a cardiovascular event than was the nondepressed group, she said. The “became depressed” group had a 44% increase in risk, compared with the nondepressed individuals. In contrast, the MACE risk in patients in the “no longer depressed” group was not significantly different from that of patients who weren’t depressed at either time point. And the MACE risk of patients who became depressed during the course of the study was no different from that of patients who remained depressed at both time points.

This is the first study of its kind, Dr. May said. Hence, the results require confirmation, ideally in a randomized clinical trial.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by Intermountain Healthcare.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: Event rate was no different in “no longer depressed” group than in “never depressed.”

Major finding: Major adverse cardiovascular events were 44% more likely in primary care patients who became depressed during a median 2.7-year period, compared with those who weren’t depressed at either time point.

Data source: An observational study of 7,550 patients screened for depression in primary care clinics.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Intermountain Healthcare. Dr. May reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Exercise Is Protective but Underutilized in Atrial Fib Patients

CHICAGO – Efforts to encourage even modest amounts of physical activity in sedentary patients with atrial fibrillation are likely to pay off in reduced risks of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, according to a report from the EurObservational Research Program Pilot Survey on Atrial Fibrillation General Registry.

“Clearly we would recommend regular physical activity for patients with atrial fibrillation on the basis of the mortality benefit we see in the registry. If we give patients with atrial fibrillation oral anticoagulation, they are protected against stroke risk, but clearly they are still dying a lot,” Dr. Marco Proietti said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

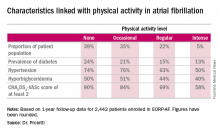

He presented 1-year follow-up data on 2,442 “real world” patients enrolled in the nine-country, observational, prospective registry, known as EORP-AF, shortly after being diagnosed with AF. One of the goals of EORP-AF is to learn whether physical exercise protects against cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in AF patients, as has been well established in the general population and in patients at high cardiovascular risk.

One striking finding was that nearly 40% of patients in EORP-AF reported engaging in no physical activity, defined for study purposes as zero to less than 3 hours of physical activity per week for less than 2 years.

The other three categories employed by investigators were “occasional,” meaning less than 3 hours per week but for 2 years or more; “regular,” defined as at least 3 hours weekly for at least 2 years; and “intense,” which required more than 7 hours of physical activity per week for at least 2 years. Levels of cardiovascular and stroke risk factors decreased progressively with increasing levels of physical activity. Only 5% of the AF patients met the ‘intense’ standard, noted Dr. Proietti of the University of Birmingham (England).

The 1-year cardiovascular mortality rate approached 6% in the no physical activity group and hovered around 1% in the other three groups. The 1-year all-cause mortality rate exceeded 12% in the no-exercise group, was 4%% in the occasional exercisers, and 1%-2% in the groups reporting regular or intense physical activity.

The 1-year composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, any thromboembolism, or a bleeding event occurred in 12% of the sedentary patients, a rate two-to-three times higher than in the others.

Updated outcomes are to be reported from the EORP-AF pilot registry after 2 and 3 years of follow-up. Meanwhile, on the basis of the success of the pilot registry, more than 10,000 patients with AF have been enrolled in the EORP-AF main registry, according to Dr. Proietti.

A study limitation, he conceded, is that the registry includes no objective measure of physical capacity, such as METS.

Session co-chair Dr. Brian Olshansky, emeritus professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, observed that the registry data raise a classic chicken-versus-egg issue: Do the sedentary patients do worse because they’re inactive, or are they inactive because they are sicker and hence have worse outcomes?

Dr. Proietti said the registry data provide some support for the latter idea, since the no-physical-activity group had higher prevalences of coronary artery disease and heart failure.

Dr. Olshansky raised another point: “It’s interesting to me that there’s a whole bunch of literature showing that elite endurance athletes – bike racers, cross country skiers – have a very high incidence of atrial fibrillation. It seems to be either an inflammatory or an autonomic issue.”

Dr. Proietti replied that he’s familiar with that extensive literature, but the EORP-AF data through 1 year don’t provide validation. While the intense physical activity group tended to have more symptomatic AF than the other groups, they were no more likely to show progression from paroxysmal to permanent AF. The much larger main registry now underway may be able to better clarify the relationship between physical activity and incidence and progression of AF, including the possibility of a U-shaped dose-response curve.

The EORP-AF registry is supported by the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Proietti reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Efforts to encourage even modest amounts of physical activity in sedentary patients with atrial fibrillation are likely to pay off in reduced risks of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, according to a report from the EurObservational Research Program Pilot Survey on Atrial Fibrillation General Registry.

“Clearly we would recommend regular physical activity for patients with atrial fibrillation on the basis of the mortality benefit we see in the registry. If we give patients with atrial fibrillation oral anticoagulation, they are protected against stroke risk, but clearly they are still dying a lot,” Dr. Marco Proietti said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

He presented 1-year follow-up data on 2,442 “real world” patients enrolled in the nine-country, observational, prospective registry, known as EORP-AF, shortly after being diagnosed with AF. One of the goals of EORP-AF is to learn whether physical exercise protects against cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in AF patients, as has been well established in the general population and in patients at high cardiovascular risk.

One striking finding was that nearly 40% of patients in EORP-AF reported engaging in no physical activity, defined for study purposes as zero to less than 3 hours of physical activity per week for less than 2 years.

The other three categories employed by investigators were “occasional,” meaning less than 3 hours per week but for 2 years or more; “regular,” defined as at least 3 hours weekly for at least 2 years; and “intense,” which required more than 7 hours of physical activity per week for at least 2 years. Levels of cardiovascular and stroke risk factors decreased progressively with increasing levels of physical activity. Only 5% of the AF patients met the ‘intense’ standard, noted Dr. Proietti of the University of Birmingham (England).

The 1-year cardiovascular mortality rate approached 6% in the no physical activity group and hovered around 1% in the other three groups. The 1-year all-cause mortality rate exceeded 12% in the no-exercise group, was 4%% in the occasional exercisers, and 1%-2% in the groups reporting regular or intense physical activity.

The 1-year composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, any thromboembolism, or a bleeding event occurred in 12% of the sedentary patients, a rate two-to-three times higher than in the others.

Updated outcomes are to be reported from the EORP-AF pilot registry after 2 and 3 years of follow-up. Meanwhile, on the basis of the success of the pilot registry, more than 10,000 patients with AF have been enrolled in the EORP-AF main registry, according to Dr. Proietti.

A study limitation, he conceded, is that the registry includes no objective measure of physical capacity, such as METS.

Session co-chair Dr. Brian Olshansky, emeritus professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, observed that the registry data raise a classic chicken-versus-egg issue: Do the sedentary patients do worse because they’re inactive, or are they inactive because they are sicker and hence have worse outcomes?

Dr. Proietti said the registry data provide some support for the latter idea, since the no-physical-activity group had higher prevalences of coronary artery disease and heart failure.