User login

EEG burst suppression pattern prognosis not always grim post cardiac arrest

WASHINGTON – , according to findings from a retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Traditionally, burst suppression patterns (BSP) in post–cardiac arrest patients, especially without anesthesia or cooling, has been considered strongly associated with poor network-level recovery, but findings reported by Krithiga Sekar, MD, PhD, and her colleagues in a poster at the meeting show that patients with BSP on EEG recover consciousness with the same frequency as do those who recover without BSP.

In fact, Dr. Sekar, an epilepsy fellow at Columbia University, New York, and her colleagues asserted that prognoses of poor outcomes are more accurately associated with characteristics of the signals themselves, with some cases of BSP acting as a neuroprotective mechanism during metabolic stress.

Dr. Sekar and her coinvestigators retrospectively studied 73 cardiac arrest patients who underwent therapeutic hypothermia with continuous video EEG monitoring at Cornell. Of those studied, 45 (62%) had BSP on EEG, a common occurrence after cardiac arrest, according to Dr. Sekar.

Of those with BSP on EEG, 14 (31%) recovered consciousness within the first 72 hours of arrest, as did 10 (36%) who recovered without BSP.

For those who did not recover, the median number of days hooked up was around 9, much longer than in other studies, which could be why more patients recovered compared with those in older literature, according to Dr. Sekar and her fellow investigators.

“The length of time for withdrawal of care was around 9 or 10 days, while much of the literature I had read had withdrawal of care within the first 4 or 5 days,” Dr. Sekar said. “If people think [BSP] is a poor prognosticator, they will withdraw care more often, and then that accumulates more data that this is a poor prognosticator.”

Of the 49 who did not recover, 12 patients in the BSP group and 10 patients in the non-BSP group had care withdrawn.

During the study, Dr. Sekar and her colleagues found two patients with spontaneous BSP, both of whom were taken off anesthetics and remained in burst suppression: one for 72 hours and one for 4 days. Both patients fully recovered consciousness.

When first induced, the patients with spontaneous BSP started with bursts that had more of a delta feature. However, once spontaneous BSP kicked in, a prominent theta feature emerged and grew increasingly more evident.

The investigators found similar theta features in patients who recovered with only induced and reduced BSP. But those who did not do well either had a flat spectra, similar to type A EEG that is correlated with poor outcomes, or had some signs of theta features within 72 hours and then lost them.

“This suggests this theta frequency activity within the bursts, maybe it signals underlying networks that are potentially recoverable and are necessary for consciousness,” Dr. Sekar explained. “In these cases, maybe they were early on available but as energy dynamics lagged behind recovery of the brain, maybe they just never got those networks to function again.”

Going forward, Dr. Sekar and her colleagues plan to do a prospective study with a longer period of observation to see the effects of these theta frequency features.

The study was supported by individual grants from the National Institutes of Health, a Leon Levy Neuroscience Fellowship Award, and several foundations. The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Sekar K et al., AES Abstract 1.097

WASHINGTON – , according to findings from a retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Traditionally, burst suppression patterns (BSP) in post–cardiac arrest patients, especially without anesthesia or cooling, has been considered strongly associated with poor network-level recovery, but findings reported by Krithiga Sekar, MD, PhD, and her colleagues in a poster at the meeting show that patients with BSP on EEG recover consciousness with the same frequency as do those who recover without BSP.

In fact, Dr. Sekar, an epilepsy fellow at Columbia University, New York, and her colleagues asserted that prognoses of poor outcomes are more accurately associated with characteristics of the signals themselves, with some cases of BSP acting as a neuroprotective mechanism during metabolic stress.

Dr. Sekar and her coinvestigators retrospectively studied 73 cardiac arrest patients who underwent therapeutic hypothermia with continuous video EEG monitoring at Cornell. Of those studied, 45 (62%) had BSP on EEG, a common occurrence after cardiac arrest, according to Dr. Sekar.

Of those with BSP on EEG, 14 (31%) recovered consciousness within the first 72 hours of arrest, as did 10 (36%) who recovered without BSP.

For those who did not recover, the median number of days hooked up was around 9, much longer than in other studies, which could be why more patients recovered compared with those in older literature, according to Dr. Sekar and her fellow investigators.

“The length of time for withdrawal of care was around 9 or 10 days, while much of the literature I had read had withdrawal of care within the first 4 or 5 days,” Dr. Sekar said. “If people think [BSP] is a poor prognosticator, they will withdraw care more often, and then that accumulates more data that this is a poor prognosticator.”

Of the 49 who did not recover, 12 patients in the BSP group and 10 patients in the non-BSP group had care withdrawn.

During the study, Dr. Sekar and her colleagues found two patients with spontaneous BSP, both of whom were taken off anesthetics and remained in burst suppression: one for 72 hours and one for 4 days. Both patients fully recovered consciousness.

When first induced, the patients with spontaneous BSP started with bursts that had more of a delta feature. However, once spontaneous BSP kicked in, a prominent theta feature emerged and grew increasingly more evident.

The investigators found similar theta features in patients who recovered with only induced and reduced BSP. But those who did not do well either had a flat spectra, similar to type A EEG that is correlated with poor outcomes, or had some signs of theta features within 72 hours and then lost them.

“This suggests this theta frequency activity within the bursts, maybe it signals underlying networks that are potentially recoverable and are necessary for consciousness,” Dr. Sekar explained. “In these cases, maybe they were early on available but as energy dynamics lagged behind recovery of the brain, maybe they just never got those networks to function again.”

Going forward, Dr. Sekar and her colleagues plan to do a prospective study with a longer period of observation to see the effects of these theta frequency features.

The study was supported by individual grants from the National Institutes of Health, a Leon Levy Neuroscience Fellowship Award, and several foundations. The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Sekar K et al., AES Abstract 1.097

WASHINGTON – , according to findings from a retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Traditionally, burst suppression patterns (BSP) in post–cardiac arrest patients, especially without anesthesia or cooling, has been considered strongly associated with poor network-level recovery, but findings reported by Krithiga Sekar, MD, PhD, and her colleagues in a poster at the meeting show that patients with BSP on EEG recover consciousness with the same frequency as do those who recover without BSP.

In fact, Dr. Sekar, an epilepsy fellow at Columbia University, New York, and her colleagues asserted that prognoses of poor outcomes are more accurately associated with characteristics of the signals themselves, with some cases of BSP acting as a neuroprotective mechanism during metabolic stress.

Dr. Sekar and her coinvestigators retrospectively studied 73 cardiac arrest patients who underwent therapeutic hypothermia with continuous video EEG monitoring at Cornell. Of those studied, 45 (62%) had BSP on EEG, a common occurrence after cardiac arrest, according to Dr. Sekar.

Of those with BSP on EEG, 14 (31%) recovered consciousness within the first 72 hours of arrest, as did 10 (36%) who recovered without BSP.

For those who did not recover, the median number of days hooked up was around 9, much longer than in other studies, which could be why more patients recovered compared with those in older literature, according to Dr. Sekar and her fellow investigators.

“The length of time for withdrawal of care was around 9 or 10 days, while much of the literature I had read had withdrawal of care within the first 4 or 5 days,” Dr. Sekar said. “If people think [BSP] is a poor prognosticator, they will withdraw care more often, and then that accumulates more data that this is a poor prognosticator.”

Of the 49 who did not recover, 12 patients in the BSP group and 10 patients in the non-BSP group had care withdrawn.

During the study, Dr. Sekar and her colleagues found two patients with spontaneous BSP, both of whom were taken off anesthetics and remained in burst suppression: one for 72 hours and one for 4 days. Both patients fully recovered consciousness.

When first induced, the patients with spontaneous BSP started with bursts that had more of a delta feature. However, once spontaneous BSP kicked in, a prominent theta feature emerged and grew increasingly more evident.

The investigators found similar theta features in patients who recovered with only induced and reduced BSP. But those who did not do well either had a flat spectra, similar to type A EEG that is correlated with poor outcomes, or had some signs of theta features within 72 hours and then lost them.

“This suggests this theta frequency activity within the bursts, maybe it signals underlying networks that are potentially recoverable and are necessary for consciousness,” Dr. Sekar explained. “In these cases, maybe they were early on available but as energy dynamics lagged behind recovery of the brain, maybe they just never got those networks to function again.”

Going forward, Dr. Sekar and her colleagues plan to do a prospective study with a longer period of observation to see the effects of these theta frequency features.

The study was supported by individual grants from the National Institutes of Health, a Leon Levy Neuroscience Fellowship Award, and several foundations. The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Sekar K et al., AES Abstract 1.097

REPORTING FROM AES 2017

Key clinical point: A better understanding of BSP in comatose patients will assist improvement for those with potential to recover.

Major finding: Fourteen patients with BSP recovered consciousness, compared with 10 patients without BSP.

Data source: Retrospective study of 73 patients who were comatose after cardiac arrest.

Disclosures: The study was supported by individual grants from the National Institutes of Health, a Leon Levy Neuroscience Fellowship Award, and several foundations. The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Sekar K et al. AES Abstract 1.097

Efficacy of neurostimulation for epilepsy underestimated with patient reports

WASHINGTON – The benefit of implanting a responsive brain stimulator for the control of refractory epilepsy may be grossly underestimated without relying on an objective measure of baseline seizure activity rather than patient reports, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

In a retrospective evaluation at one center, the efficacy of the Responsive Neurostimulation System (RNS) came nowhere near that observed in the pivotal clinical trial until objective measures of seizure activity were analyzed, reported Michael Young, DO, a neurophysiology fellow in the department of neurology at the University of California, Irvine (UCI).

In this study, investigators evaluated seizure frequency in the first 2 months after RNS implantation with the ECoG component of the RNS device. They assessed change in seizure frequency relative to this baseline at 3, 6, and 12 months, and also compared the reduction in seizures against the patient self-report of baseline seizure activity.

The differences were large. On patient report, the reduction in seizure activity at month 3 was just 10%, compared with 85% when measured on ECoG.

“Our results with the RNS compare favorably to the pivotal trial only when using the ECoG seizure frequency baseline. The reason for this discrepancy is due to underreporting of seizures by patients and consequently a falsely low seizure frequency,” Dr. Young explained at the meeting.

The RNS system has been implanted for refractory focal or partial seizures in adult patients at UCI since 2015. The device is indicated for adjunctive use in patients not adequately controlled on at least two antiepileptic medications. Twelve patients have been treated, but two were excluded from this analysis because they had surgical resection at the time of the RNS implantation and one because of an infection related to the implantation.

In general, patients treated at UCI had characteristics similar to those in the pivotal trial, which was published more than 3 years ago (Epilepsia. 2014;55[3]:432-41). In that 191-patient trial, the reduction in seizure frequency at the end of 5 months of blinded analysis with RNS was 37.9% versus 17.3% for a sham procedure. Progressive further reductions in seizure activity were observed during an extended open-label follow-up.

In the UCI analysis, the mean reduction in seizure frequency at 12 months was 56% relative to the patient-reported baseline but 78% on the basis of the ECoG analysis. Although only four of the nine patients have 12 or more months of follow-up, three were considered to be responders to RNS whether evaluated in relation to the patient-reported baseline seizure activity or in relation to ECoG. The responder rate at 3 months on the basis of patient-reported baseline activity, however, was only 56%, compared with 100% based on ECoG.

“The big issue is underreporting of seizures by patients,” Dr. Young explained. He cited numerous other studies demonstrating the same phenomenon. He noted that noncompliance is only one reason patients underreport. In many cases, patients are simply unaware of seizure activity.

Based on these data, “we think ECoG may be a more objective way to track patient response to RNS,” Dr. Young said. He acknowledged that the number of patients limits this study and suggested that larger studies are needed to confirm the findings.

Dr. Young reported having no potential conflicts of interest related to this topic.

SOURCE: Young M et al. AES abstract 3.109.

WASHINGTON – The benefit of implanting a responsive brain stimulator for the control of refractory epilepsy may be grossly underestimated without relying on an objective measure of baseline seizure activity rather than patient reports, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

In a retrospective evaluation at one center, the efficacy of the Responsive Neurostimulation System (RNS) came nowhere near that observed in the pivotal clinical trial until objective measures of seizure activity were analyzed, reported Michael Young, DO, a neurophysiology fellow in the department of neurology at the University of California, Irvine (UCI).

In this study, investigators evaluated seizure frequency in the first 2 months after RNS implantation with the ECoG component of the RNS device. They assessed change in seizure frequency relative to this baseline at 3, 6, and 12 months, and also compared the reduction in seizures against the patient self-report of baseline seizure activity.

The differences were large. On patient report, the reduction in seizure activity at month 3 was just 10%, compared with 85% when measured on ECoG.

“Our results with the RNS compare favorably to the pivotal trial only when using the ECoG seizure frequency baseline. The reason for this discrepancy is due to underreporting of seizures by patients and consequently a falsely low seizure frequency,” Dr. Young explained at the meeting.

The RNS system has been implanted for refractory focal or partial seizures in adult patients at UCI since 2015. The device is indicated for adjunctive use in patients not adequately controlled on at least two antiepileptic medications. Twelve patients have been treated, but two were excluded from this analysis because they had surgical resection at the time of the RNS implantation and one because of an infection related to the implantation.

In general, patients treated at UCI had characteristics similar to those in the pivotal trial, which was published more than 3 years ago (Epilepsia. 2014;55[3]:432-41). In that 191-patient trial, the reduction in seizure frequency at the end of 5 months of blinded analysis with RNS was 37.9% versus 17.3% for a sham procedure. Progressive further reductions in seizure activity were observed during an extended open-label follow-up.

In the UCI analysis, the mean reduction in seizure frequency at 12 months was 56% relative to the patient-reported baseline but 78% on the basis of the ECoG analysis. Although only four of the nine patients have 12 or more months of follow-up, three were considered to be responders to RNS whether evaluated in relation to the patient-reported baseline seizure activity or in relation to ECoG. The responder rate at 3 months on the basis of patient-reported baseline activity, however, was only 56%, compared with 100% based on ECoG.

“The big issue is underreporting of seizures by patients,” Dr. Young explained. He cited numerous other studies demonstrating the same phenomenon. He noted that noncompliance is only one reason patients underreport. In many cases, patients are simply unaware of seizure activity.

Based on these data, “we think ECoG may be a more objective way to track patient response to RNS,” Dr. Young said. He acknowledged that the number of patients limits this study and suggested that larger studies are needed to confirm the findings.

Dr. Young reported having no potential conflicts of interest related to this topic.

SOURCE: Young M et al. AES abstract 3.109.

WASHINGTON – The benefit of implanting a responsive brain stimulator for the control of refractory epilepsy may be grossly underestimated without relying on an objective measure of baseline seizure activity rather than patient reports, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

In a retrospective evaluation at one center, the efficacy of the Responsive Neurostimulation System (RNS) came nowhere near that observed in the pivotal clinical trial until objective measures of seizure activity were analyzed, reported Michael Young, DO, a neurophysiology fellow in the department of neurology at the University of California, Irvine (UCI).

In this study, investigators evaluated seizure frequency in the first 2 months after RNS implantation with the ECoG component of the RNS device. They assessed change in seizure frequency relative to this baseline at 3, 6, and 12 months, and also compared the reduction in seizures against the patient self-report of baseline seizure activity.

The differences were large. On patient report, the reduction in seizure activity at month 3 was just 10%, compared with 85% when measured on ECoG.

“Our results with the RNS compare favorably to the pivotal trial only when using the ECoG seizure frequency baseline. The reason for this discrepancy is due to underreporting of seizures by patients and consequently a falsely low seizure frequency,” Dr. Young explained at the meeting.

The RNS system has been implanted for refractory focal or partial seizures in adult patients at UCI since 2015. The device is indicated for adjunctive use in patients not adequately controlled on at least two antiepileptic medications. Twelve patients have been treated, but two were excluded from this analysis because they had surgical resection at the time of the RNS implantation and one because of an infection related to the implantation.

In general, patients treated at UCI had characteristics similar to those in the pivotal trial, which was published more than 3 years ago (Epilepsia. 2014;55[3]:432-41). In that 191-patient trial, the reduction in seizure frequency at the end of 5 months of blinded analysis with RNS was 37.9% versus 17.3% for a sham procedure. Progressive further reductions in seizure activity were observed during an extended open-label follow-up.

In the UCI analysis, the mean reduction in seizure frequency at 12 months was 56% relative to the patient-reported baseline but 78% on the basis of the ECoG analysis. Although only four of the nine patients have 12 or more months of follow-up, three were considered to be responders to RNS whether evaluated in relation to the patient-reported baseline seizure activity or in relation to ECoG. The responder rate at 3 months on the basis of patient-reported baseline activity, however, was only 56%, compared with 100% based on ECoG.

“The big issue is underreporting of seizures by patients,” Dr. Young explained. He cited numerous other studies demonstrating the same phenomenon. He noted that noncompliance is only one reason patients underreport. In many cases, patients are simply unaware of seizure activity.

Based on these data, “we think ECoG may be a more objective way to track patient response to RNS,” Dr. Young said. He acknowledged that the number of patients limits this study and suggested that larger studies are needed to confirm the findings.

Dr. Young reported having no potential conflicts of interest related to this topic.

SOURCE: Young M et al. AES abstract 3.109.

REPORTING FROM AES 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 3 months after implantation, seizure activity was reduced 10% by patient report but 85% by objective measurement.

Data source: Retrospective study of nine patients implanted with the Responsive Neurostimulation System.

Disclosures: Dr. Young reported having no potential conflicts of interest related to this topic.

Source: Young M et al. AES abstract 3.109.

MRI-guided focused ultrasound shows promise for subcortical epilepsy

WASHINGTON – MRI-guided focused ultrasound (FUS) is now being employed on an experimental basis to treat deep subcortical lesions, such as hypothalamic hamartoma, to control intractable epilepsy, according to an expert summary of a “hot topic” presented at the American Epilepsy Society annual meeting.

“If the risk of FUS is as low as we expect, it could change our paradigm,” reported Nathan B. Fountain, MD, director of the F.E. Dreifuss Comprehensive Epilepsy Program at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

FUS has been used clinically for the treatment of uterine fibroids since 2004, according to an overview provided by Dr. Fountain. Clinical studies of MRI-guided FUS for lesions in the brain began in 2009. The approval of MRI-guided FUS thalamotomy for essential tumor in 2016 was based on a pivotal trial led by Jeffrey Elias, MD, a colleague of Dr. Fountain’s at the University of Virginia (N Engl J Med. 2016;375:730-9). Many of the principles for treating subcortical lesions causing epilepsy are the same as those for treating essential tremor.

Under MRI guidance, FUS is delivered via a helmet with 1,024 transducers. These focus sound waves to a highly targeted area of the brain, resulting in thermal ablation. The treatment is noninvasive in the sense that no craniotomy is involved. It can be delivered without anesthesia. When used to treat essential tremor in awake patients, MRI-guided FUS confirms the target when the tremor resolves.

“There is no injury to the brain as far as we can tell,” reported Dr. Fountain, referring to the tremor studies.

Because the thermal ablation is delivered by sound waves, this approach appears to be safer to structures surrounding the lesion than would be anticipated with energy delivered by radiation. For treatment of lesions in the hypothalamus, where surrounding tissue is responsible for important brain functions, the apparent low risk of collateral damage is a major potential advantage, according to Dr. Fountain.

Although Dr. Fountain conceded that the term “subcortical” is not commonly used to describe epilepsy lesions, he considers it appropriate to explain the role of MRI-guided FUS. Without technical advancements, this tool is not appropriate for the cortical lesions that are responsible for the majority of epileptic seizures. Rather, lesions must be positioned deep in the skull to be in the “envelope” where energy can be concentrated. Lesions in the temporal or hippocampal areas of the brain, for example, will not be suitable without technical advances.

Due to its position in the brain, “hypothalamic hamartoma is the prototype lesion,” Dr. Fountain reported. Importantly, these and other lesions within the envelope where energy can be targeted are the most difficult to treat with other options. Due to the need to transverse much of the brain to reach these areas, open surgery is often not practical. Even though Dr. Fountain acknowledged that MRI-guided stereotactic laser has been proposed for these types of lesions, the laser must also transverse vulnerable structures of the brain that can be avoided with MR-guided FUS.

Results on the first patient in a planned pediatric treatment series with MRI-guided FUS were presented at the AES annual meeting by Travis Tierney, MD, PhD, a neurosurgeon associated with Nicklaus Children’s Hospital in Miami. According to the data presented by Dr. Tierney, the 21-year-old patient was treated for a hypothalamic hamartoma. She was rendered seizure free and had no complications.

An adult series is now recruiting candidates, according to Dr. Fountain. He reported that adults of at least 18 years of age with intractable epilepsy due to subcortical lesions in the central envelope suitable for MRI-guided FUS are eligible if they have at least three seizures per month while taking at least two antiepileptic drugs. He encouraged referrals.

“The primary outcome will be just to demonstrate that a lesion can be created,” Dr. Fountain said. He reported that the planned enrollment of 15 subjects would not be sufficient to draw conclusions about efficacy “unless, of course, we eliminate everyone’s seizures – and that would be useful – but that is still a secondary outcome,”

There are a number of applications in neurology beyond treatment of tremors and epilepsy that are also being considered for MRI-guided FUS, Dr. Fountain reported. This could include, for example, clot lysis in stroke, but he indicated that there are a number of reasons to be particularly optimistic about its potential role in the treatment intractable epilepsy due to subcortical lesions. This strategy seems feasible in a condition with limited treatment options.

WASHINGTON – MRI-guided focused ultrasound (FUS) is now being employed on an experimental basis to treat deep subcortical lesions, such as hypothalamic hamartoma, to control intractable epilepsy, according to an expert summary of a “hot topic” presented at the American Epilepsy Society annual meeting.

“If the risk of FUS is as low as we expect, it could change our paradigm,” reported Nathan B. Fountain, MD, director of the F.E. Dreifuss Comprehensive Epilepsy Program at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

FUS has been used clinically for the treatment of uterine fibroids since 2004, according to an overview provided by Dr. Fountain. Clinical studies of MRI-guided FUS for lesions in the brain began in 2009. The approval of MRI-guided FUS thalamotomy for essential tumor in 2016 was based on a pivotal trial led by Jeffrey Elias, MD, a colleague of Dr. Fountain’s at the University of Virginia (N Engl J Med. 2016;375:730-9). Many of the principles for treating subcortical lesions causing epilepsy are the same as those for treating essential tremor.

Under MRI guidance, FUS is delivered via a helmet with 1,024 transducers. These focus sound waves to a highly targeted area of the brain, resulting in thermal ablation. The treatment is noninvasive in the sense that no craniotomy is involved. It can be delivered without anesthesia. When used to treat essential tremor in awake patients, MRI-guided FUS confirms the target when the tremor resolves.

“There is no injury to the brain as far as we can tell,” reported Dr. Fountain, referring to the tremor studies.

Because the thermal ablation is delivered by sound waves, this approach appears to be safer to structures surrounding the lesion than would be anticipated with energy delivered by radiation. For treatment of lesions in the hypothalamus, where surrounding tissue is responsible for important brain functions, the apparent low risk of collateral damage is a major potential advantage, according to Dr. Fountain.

Although Dr. Fountain conceded that the term “subcortical” is not commonly used to describe epilepsy lesions, he considers it appropriate to explain the role of MRI-guided FUS. Without technical advancements, this tool is not appropriate for the cortical lesions that are responsible for the majority of epileptic seizures. Rather, lesions must be positioned deep in the skull to be in the “envelope” where energy can be concentrated. Lesions in the temporal or hippocampal areas of the brain, for example, will not be suitable without technical advances.

Due to its position in the brain, “hypothalamic hamartoma is the prototype lesion,” Dr. Fountain reported. Importantly, these and other lesions within the envelope where energy can be targeted are the most difficult to treat with other options. Due to the need to transverse much of the brain to reach these areas, open surgery is often not practical. Even though Dr. Fountain acknowledged that MRI-guided stereotactic laser has been proposed for these types of lesions, the laser must also transverse vulnerable structures of the brain that can be avoided with MR-guided FUS.

Results on the first patient in a planned pediatric treatment series with MRI-guided FUS were presented at the AES annual meeting by Travis Tierney, MD, PhD, a neurosurgeon associated with Nicklaus Children’s Hospital in Miami. According to the data presented by Dr. Tierney, the 21-year-old patient was treated for a hypothalamic hamartoma. She was rendered seizure free and had no complications.

An adult series is now recruiting candidates, according to Dr. Fountain. He reported that adults of at least 18 years of age with intractable epilepsy due to subcortical lesions in the central envelope suitable for MRI-guided FUS are eligible if they have at least three seizures per month while taking at least two antiepileptic drugs. He encouraged referrals.

“The primary outcome will be just to demonstrate that a lesion can be created,” Dr. Fountain said. He reported that the planned enrollment of 15 subjects would not be sufficient to draw conclusions about efficacy “unless, of course, we eliminate everyone’s seizures – and that would be useful – but that is still a secondary outcome,”

There are a number of applications in neurology beyond treatment of tremors and epilepsy that are also being considered for MRI-guided FUS, Dr. Fountain reported. This could include, for example, clot lysis in stroke, but he indicated that there are a number of reasons to be particularly optimistic about its potential role in the treatment intractable epilepsy due to subcortical lesions. This strategy seems feasible in a condition with limited treatment options.

WASHINGTON – MRI-guided focused ultrasound (FUS) is now being employed on an experimental basis to treat deep subcortical lesions, such as hypothalamic hamartoma, to control intractable epilepsy, according to an expert summary of a “hot topic” presented at the American Epilepsy Society annual meeting.

“If the risk of FUS is as low as we expect, it could change our paradigm,” reported Nathan B. Fountain, MD, director of the F.E. Dreifuss Comprehensive Epilepsy Program at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

FUS has been used clinically for the treatment of uterine fibroids since 2004, according to an overview provided by Dr. Fountain. Clinical studies of MRI-guided FUS for lesions in the brain began in 2009. The approval of MRI-guided FUS thalamotomy for essential tumor in 2016 was based on a pivotal trial led by Jeffrey Elias, MD, a colleague of Dr. Fountain’s at the University of Virginia (N Engl J Med. 2016;375:730-9). Many of the principles for treating subcortical lesions causing epilepsy are the same as those for treating essential tremor.

Under MRI guidance, FUS is delivered via a helmet with 1,024 transducers. These focus sound waves to a highly targeted area of the brain, resulting in thermal ablation. The treatment is noninvasive in the sense that no craniotomy is involved. It can be delivered without anesthesia. When used to treat essential tremor in awake patients, MRI-guided FUS confirms the target when the tremor resolves.

“There is no injury to the brain as far as we can tell,” reported Dr. Fountain, referring to the tremor studies.

Because the thermal ablation is delivered by sound waves, this approach appears to be safer to structures surrounding the lesion than would be anticipated with energy delivered by radiation. For treatment of lesions in the hypothalamus, where surrounding tissue is responsible for important brain functions, the apparent low risk of collateral damage is a major potential advantage, according to Dr. Fountain.

Although Dr. Fountain conceded that the term “subcortical” is not commonly used to describe epilepsy lesions, he considers it appropriate to explain the role of MRI-guided FUS. Without technical advancements, this tool is not appropriate for the cortical lesions that are responsible for the majority of epileptic seizures. Rather, lesions must be positioned deep in the skull to be in the “envelope” where energy can be concentrated. Lesions in the temporal or hippocampal areas of the brain, for example, will not be suitable without technical advances.

Due to its position in the brain, “hypothalamic hamartoma is the prototype lesion,” Dr. Fountain reported. Importantly, these and other lesions within the envelope where energy can be targeted are the most difficult to treat with other options. Due to the need to transverse much of the brain to reach these areas, open surgery is often not practical. Even though Dr. Fountain acknowledged that MRI-guided stereotactic laser has been proposed for these types of lesions, the laser must also transverse vulnerable structures of the brain that can be avoided with MR-guided FUS.

Results on the first patient in a planned pediatric treatment series with MRI-guided FUS were presented at the AES annual meeting by Travis Tierney, MD, PhD, a neurosurgeon associated with Nicklaus Children’s Hospital in Miami. According to the data presented by Dr. Tierney, the 21-year-old patient was treated for a hypothalamic hamartoma. She was rendered seizure free and had no complications.

An adult series is now recruiting candidates, according to Dr. Fountain. He reported that adults of at least 18 years of age with intractable epilepsy due to subcortical lesions in the central envelope suitable for MRI-guided FUS are eligible if they have at least three seizures per month while taking at least two antiepileptic drugs. He encouraged referrals.

“The primary outcome will be just to demonstrate that a lesion can be created,” Dr. Fountain said. He reported that the planned enrollment of 15 subjects would not be sufficient to draw conclusions about efficacy “unless, of course, we eliminate everyone’s seizures – and that would be useful – but that is still a secondary outcome,”

There are a number of applications in neurology beyond treatment of tremors and epilepsy that are also being considered for MRI-guided FUS, Dr. Fountain reported. This could include, for example, clot lysis in stroke, but he indicated that there are a number of reasons to be particularly optimistic about its potential role in the treatment intractable epilepsy due to subcortical lesions. This strategy seems feasible in a condition with limited treatment options.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AES 2017

Promising add-on therapy for neonatal seizures found active in safety study

WASHINGTON – presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“This is an early-phase trial, but it did associate bumetanide with an additional reduction in seizure burden relative to phenobarbital alone,” reported Janet S. Soul, MD, director of the fetal-neonatal neurology program at Boston Children’s Hospital. She added, “The adverse events observed were not substantially different in the group that received the experimental agent.”

Of the 111 neonates with documented seizures enrolled at four participating hospitals, 43 proceeded to randomization if their seizures proved to be refractory to standard doses of phenobarbital. After randomization, the next dose of phenobarbital was administered either with placebo or with 0.1, 0.2, or 0.3 mg/kg of bumetanide. Seizure burden was evaluated at 0-2, 2-4, and 0-4 hours after study-drug administration and compared with the burden during the 2 hours before treatment.

All three doses were active, reducing the seizure burden by a median of 41%-75% in a dose-dependent manner. Whether assessed in the first 2 hours or the first 4 hours, the efficacy of bumetanide was significantly greater in those with the greatest, relative to the least, baseline seizure burden (P = .01 for hours 0-2; P = .04 for hours 0-4). The median seizure burden during the baseline period was higher in the 27 children randomized to bumetanide (114 minutes) relative to those randomized to placebo (33 minutes), although researchers attributed this to random effects in a small study.

The evidence of antiseizure activity from bumetanide as an add-on to phenobarbital is consistent with its mechanism of action, which is blockading the chloride transporter NKCC1. In the immature neurons of neonates, NKCC1 is highly expressed, and there is basic scientific evidence that this impairs the efficacy of gamma-aminobutyric acid–receptor agonists like phenobarbital, according to Dr. Soul. The hypothesis driving the study of bumetanide is that blockading NKCC1 would improve the efficacy of phenobarbital while adding its own antiseizure effects, which together could potentially provide synergistic benefit.

The efficacy and the safety of this study are somewhat discordant with a previously published study evaluating bumetanide in 14 neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) seizures (Lancet Neurol 2015;14:469-77). Even though there were seizure reductions in five children in this other series, which did not include a control arm, there were three cases of hearing loss considered potentially related to bumetanide. The authors of that study concluded that efficacy was not shown.

There were also three cases of hearing loss in the randomized trial presented by Dr. Soul, but one occurred in the placebo group. Although the potential for ototoxicity “still needs to be addressed” in the next set of studies, Dr. Soul noted that hearing loss in children with epilepsy is common and has numerous potential etiologies. Based on these data, she concluded, “All serious adverse events were related to severe HIE with multiorgan dysfunction and/or withdrawal of care for poor prognosis.”

Among nonserious adverse events, diuresis was the only one found significantly more common in the bumetanide group (P = .02).

Phenobarbital has been a standard in the treatment of neonatal seizures for several decades despite the substantial proportion of children who do not achieve an adequate response, according to Dr. Soul. She noted that bumetanide is one of several agents being evaluated as an adjunctive agent. For example, a phase 2 crossover trial with levetiracetam is now underway. She suggested that there is reason for optimism about gaining new treatments for neonates in an area in which she believes there are unmet needs.

“I think we may see a phase 2 trial with bumetanide within a year or 2,” Dr. Soul said. If bumetanide moves forward, she expects its role to be primarily for the treatment of acute seizures caused by HIE, stroke, or hemorrhage. She is less optimistic about its benefit for seizures caused by other etiologies, such as brain malformations.

SOURCE: Soul J Abstract 2.426

WASHINGTON – presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“This is an early-phase trial, but it did associate bumetanide with an additional reduction in seizure burden relative to phenobarbital alone,” reported Janet S. Soul, MD, director of the fetal-neonatal neurology program at Boston Children’s Hospital. She added, “The adverse events observed were not substantially different in the group that received the experimental agent.”

Of the 111 neonates with documented seizures enrolled at four participating hospitals, 43 proceeded to randomization if their seizures proved to be refractory to standard doses of phenobarbital. After randomization, the next dose of phenobarbital was administered either with placebo or with 0.1, 0.2, or 0.3 mg/kg of bumetanide. Seizure burden was evaluated at 0-2, 2-4, and 0-4 hours after study-drug administration and compared with the burden during the 2 hours before treatment.

All three doses were active, reducing the seizure burden by a median of 41%-75% in a dose-dependent manner. Whether assessed in the first 2 hours or the first 4 hours, the efficacy of bumetanide was significantly greater in those with the greatest, relative to the least, baseline seizure burden (P = .01 for hours 0-2; P = .04 for hours 0-4). The median seizure burden during the baseline period was higher in the 27 children randomized to bumetanide (114 minutes) relative to those randomized to placebo (33 minutes), although researchers attributed this to random effects in a small study.

The evidence of antiseizure activity from bumetanide as an add-on to phenobarbital is consistent with its mechanism of action, which is blockading the chloride transporter NKCC1. In the immature neurons of neonates, NKCC1 is highly expressed, and there is basic scientific evidence that this impairs the efficacy of gamma-aminobutyric acid–receptor agonists like phenobarbital, according to Dr. Soul. The hypothesis driving the study of bumetanide is that blockading NKCC1 would improve the efficacy of phenobarbital while adding its own antiseizure effects, which together could potentially provide synergistic benefit.

The efficacy and the safety of this study are somewhat discordant with a previously published study evaluating bumetanide in 14 neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) seizures (Lancet Neurol 2015;14:469-77). Even though there were seizure reductions in five children in this other series, which did not include a control arm, there were three cases of hearing loss considered potentially related to bumetanide. The authors of that study concluded that efficacy was not shown.

There were also three cases of hearing loss in the randomized trial presented by Dr. Soul, but one occurred in the placebo group. Although the potential for ototoxicity “still needs to be addressed” in the next set of studies, Dr. Soul noted that hearing loss in children with epilepsy is common and has numerous potential etiologies. Based on these data, she concluded, “All serious adverse events were related to severe HIE with multiorgan dysfunction and/or withdrawal of care for poor prognosis.”

Among nonserious adverse events, diuresis was the only one found significantly more common in the bumetanide group (P = .02).

Phenobarbital has been a standard in the treatment of neonatal seizures for several decades despite the substantial proportion of children who do not achieve an adequate response, according to Dr. Soul. She noted that bumetanide is one of several agents being evaluated as an adjunctive agent. For example, a phase 2 crossover trial with levetiracetam is now underway. She suggested that there is reason for optimism about gaining new treatments for neonates in an area in which she believes there are unmet needs.

“I think we may see a phase 2 trial with bumetanide within a year or 2,” Dr. Soul said. If bumetanide moves forward, she expects its role to be primarily for the treatment of acute seizures caused by HIE, stroke, or hemorrhage. She is less optimistic about its benefit for seizures caused by other etiologies, such as brain malformations.

SOURCE: Soul J Abstract 2.426

WASHINGTON – presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“This is an early-phase trial, but it did associate bumetanide with an additional reduction in seizure burden relative to phenobarbital alone,” reported Janet S. Soul, MD, director of the fetal-neonatal neurology program at Boston Children’s Hospital. She added, “The adverse events observed were not substantially different in the group that received the experimental agent.”

Of the 111 neonates with documented seizures enrolled at four participating hospitals, 43 proceeded to randomization if their seizures proved to be refractory to standard doses of phenobarbital. After randomization, the next dose of phenobarbital was administered either with placebo or with 0.1, 0.2, or 0.3 mg/kg of bumetanide. Seizure burden was evaluated at 0-2, 2-4, and 0-4 hours after study-drug administration and compared with the burden during the 2 hours before treatment.

All three doses were active, reducing the seizure burden by a median of 41%-75% in a dose-dependent manner. Whether assessed in the first 2 hours or the first 4 hours, the efficacy of bumetanide was significantly greater in those with the greatest, relative to the least, baseline seizure burden (P = .01 for hours 0-2; P = .04 for hours 0-4). The median seizure burden during the baseline period was higher in the 27 children randomized to bumetanide (114 minutes) relative to those randomized to placebo (33 minutes), although researchers attributed this to random effects in a small study.

The evidence of antiseizure activity from bumetanide as an add-on to phenobarbital is consistent with its mechanism of action, which is blockading the chloride transporter NKCC1. In the immature neurons of neonates, NKCC1 is highly expressed, and there is basic scientific evidence that this impairs the efficacy of gamma-aminobutyric acid–receptor agonists like phenobarbital, according to Dr. Soul. The hypothesis driving the study of bumetanide is that blockading NKCC1 would improve the efficacy of phenobarbital while adding its own antiseizure effects, which together could potentially provide synergistic benefit.

The efficacy and the safety of this study are somewhat discordant with a previously published study evaluating bumetanide in 14 neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) seizures (Lancet Neurol 2015;14:469-77). Even though there were seizure reductions in five children in this other series, which did not include a control arm, there were three cases of hearing loss considered potentially related to bumetanide. The authors of that study concluded that efficacy was not shown.

There were also three cases of hearing loss in the randomized trial presented by Dr. Soul, but one occurred in the placebo group. Although the potential for ototoxicity “still needs to be addressed” in the next set of studies, Dr. Soul noted that hearing loss in children with epilepsy is common and has numerous potential etiologies. Based on these data, she concluded, “All serious adverse events were related to severe HIE with multiorgan dysfunction and/or withdrawal of care for poor prognosis.”

Among nonserious adverse events, diuresis was the only one found significantly more common in the bumetanide group (P = .02).

Phenobarbital has been a standard in the treatment of neonatal seizures for several decades despite the substantial proportion of children who do not achieve an adequate response, according to Dr. Soul. She noted that bumetanide is one of several agents being evaluated as an adjunctive agent. For example, a phase 2 crossover trial with levetiracetam is now underway. She suggested that there is reason for optimism about gaining new treatments for neonates in an area in which she believes there are unmet needs.

“I think we may see a phase 2 trial with bumetanide within a year or 2,” Dr. Soul said. If bumetanide moves forward, she expects its role to be primarily for the treatment of acute seizures caused by HIE, stroke, or hemorrhage. She is less optimistic about its benefit for seizures caused by other etiologies, such as brain malformations.

SOURCE: Soul J Abstract 2.426

REPORTING FROM AES 2017

Key clinical point: Bumetanide is associated with antiseizure activity as add-on therapy to phenobarbital for neonatal seizures.

Major finding: Relative to pretreatment, there was greater reduction in seizure burden (P = .01) at 4 hours in those with the highest seizure burden.

Data source: Randomized, double-blind phase 1/2 trial.

Disclosures: Dr. Soul reports no potential conflicts of interest related to this topic.

Source: Soul J et al. Abstract 2.426

ACTH and other standard treatments prove best for infantile spasms

WASHINGTON – Standard infantile spasm therapies such as adrenocorticotropic hormone appear to be significantly more effective than nonstandard therapies, according to a prospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

If infants currently treated with nonstandard therapies switched to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), there would be an increase of “one additional responder for every four infants with infantile spasms,” according to Renee Shellhaas, MD, a pediatric neurologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Shellhaas and her colleagues conducted a prospective study of 352 infants recorded to have spasms in the National Infantile Spasms Consortium from 2012 to 2016 and compared successful responses with the use of ACTH and other standard therapies against those with nonstandard therapies. They defined a successful response as a patient who did not take any other medication for infantile spasms for 60 days and had no infantile spasms for 30 days after finishing 30 days of treatment. Infants were split into four treatment arms: ACTH (n = 150), vigabatrin (68), oral steroids (90), and nonstandard therapies (44). Nonstandard therapies included topiramate, levetiracetam, clobazam, zonisamide, ketogenic diet, oxcarbazepine, and phenobarbital.

The proportion of male infants across all arms was 50%-64%, with an average age of 6.2 months in the ACTH group, 5.5 months in the vigabatrin group, 6.7 months in the oral steroids group, and 5.5 months in the nonstandard group. A majority of infants across all arms had hypsarrhythmia on EEG, ranging from 57% to 84%.

Dr. Shellhaas and her colleagues sought to answer the question, “What would happen if this infant had been treated with ACTH instead of the given medication?” They controlled these comparisons for selection bias by weighting them for various factors that may have increased the odds of using the comparison treatment. They also controlled for potential medical center effects, but did not adjust for dosing regimen.

If the infants who had received nonstandard therapies had instead received ACTH, their response rate would have improved from 5% to 32%, according to this analysis (P less than .01).

In comparisons against other standard treatments, response rates would not have been significantly better if patients had instead received ACTH: 29% for vigabatrin vs. an estimated 37% for ACTH and 46% for oral steroids vs. an estimated 44% for ACTH.

If there was one thing to take away from this, it is that nonstandard therapies do not work nearly as well as ACTH or other standard treatments,” Dr. Shellhaas said. “It is crucial to treat these infants with treatments that are effective.”

Dr. Shellhaas and her associates uncovered certain clinical factors associated with treatment selections. Among infants with unknown infantile spasm etiology, 30% were given nonstandard treatment, whereas 47% received ACTH. Infants who were not already on antiepileptic drugs more often received nonstandard therapies than ACTH (45% vs. 17%).

However, ACTH was still more likely to be given over nonstandard therapies to infants who had hypsarrhythmia (84% vs. 57%) or a normal head circumference (77% vs. 57%).

Dr. Shellhaas reported no relevant financial disclosures. The Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation funded the study.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: AES 2017 abstract 1.303

WASHINGTON – Standard infantile spasm therapies such as adrenocorticotropic hormone appear to be significantly more effective than nonstandard therapies, according to a prospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

If infants currently treated with nonstandard therapies switched to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), there would be an increase of “one additional responder for every four infants with infantile spasms,” according to Renee Shellhaas, MD, a pediatric neurologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Shellhaas and her colleagues conducted a prospective study of 352 infants recorded to have spasms in the National Infantile Spasms Consortium from 2012 to 2016 and compared successful responses with the use of ACTH and other standard therapies against those with nonstandard therapies. They defined a successful response as a patient who did not take any other medication for infantile spasms for 60 days and had no infantile spasms for 30 days after finishing 30 days of treatment. Infants were split into four treatment arms: ACTH (n = 150), vigabatrin (68), oral steroids (90), and nonstandard therapies (44). Nonstandard therapies included topiramate, levetiracetam, clobazam, zonisamide, ketogenic diet, oxcarbazepine, and phenobarbital.

The proportion of male infants across all arms was 50%-64%, with an average age of 6.2 months in the ACTH group, 5.5 months in the vigabatrin group, 6.7 months in the oral steroids group, and 5.5 months in the nonstandard group. A majority of infants across all arms had hypsarrhythmia on EEG, ranging from 57% to 84%.

Dr. Shellhaas and her colleagues sought to answer the question, “What would happen if this infant had been treated with ACTH instead of the given medication?” They controlled these comparisons for selection bias by weighting them for various factors that may have increased the odds of using the comparison treatment. They also controlled for potential medical center effects, but did not adjust for dosing regimen.

If the infants who had received nonstandard therapies had instead received ACTH, their response rate would have improved from 5% to 32%, according to this analysis (P less than .01).

In comparisons against other standard treatments, response rates would not have been significantly better if patients had instead received ACTH: 29% for vigabatrin vs. an estimated 37% for ACTH and 46% for oral steroids vs. an estimated 44% for ACTH.

If there was one thing to take away from this, it is that nonstandard therapies do not work nearly as well as ACTH or other standard treatments,” Dr. Shellhaas said. “It is crucial to treat these infants with treatments that are effective.”

Dr. Shellhaas and her associates uncovered certain clinical factors associated with treatment selections. Among infants with unknown infantile spasm etiology, 30% were given nonstandard treatment, whereas 47% received ACTH. Infants who were not already on antiepileptic drugs more often received nonstandard therapies than ACTH (45% vs. 17%).

However, ACTH was still more likely to be given over nonstandard therapies to infants who had hypsarrhythmia (84% vs. 57%) or a normal head circumference (77% vs. 57%).

Dr. Shellhaas reported no relevant financial disclosures. The Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation funded the study.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: AES 2017 abstract 1.303

WASHINGTON – Standard infantile spasm therapies such as adrenocorticotropic hormone appear to be significantly more effective than nonstandard therapies, according to a prospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

If infants currently treated with nonstandard therapies switched to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), there would be an increase of “one additional responder for every four infants with infantile spasms,” according to Renee Shellhaas, MD, a pediatric neurologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Shellhaas and her colleagues conducted a prospective study of 352 infants recorded to have spasms in the National Infantile Spasms Consortium from 2012 to 2016 and compared successful responses with the use of ACTH and other standard therapies against those with nonstandard therapies. They defined a successful response as a patient who did not take any other medication for infantile spasms for 60 days and had no infantile spasms for 30 days after finishing 30 days of treatment. Infants were split into four treatment arms: ACTH (n = 150), vigabatrin (68), oral steroids (90), and nonstandard therapies (44). Nonstandard therapies included topiramate, levetiracetam, clobazam, zonisamide, ketogenic diet, oxcarbazepine, and phenobarbital.

The proportion of male infants across all arms was 50%-64%, with an average age of 6.2 months in the ACTH group, 5.5 months in the vigabatrin group, 6.7 months in the oral steroids group, and 5.5 months in the nonstandard group. A majority of infants across all arms had hypsarrhythmia on EEG, ranging from 57% to 84%.

Dr. Shellhaas and her colleagues sought to answer the question, “What would happen if this infant had been treated with ACTH instead of the given medication?” They controlled these comparisons for selection bias by weighting them for various factors that may have increased the odds of using the comparison treatment. They also controlled for potential medical center effects, but did not adjust for dosing regimen.

If the infants who had received nonstandard therapies had instead received ACTH, their response rate would have improved from 5% to 32%, according to this analysis (P less than .01).

In comparisons against other standard treatments, response rates would not have been significantly better if patients had instead received ACTH: 29% for vigabatrin vs. an estimated 37% for ACTH and 46% for oral steroids vs. an estimated 44% for ACTH.

If there was one thing to take away from this, it is that nonstandard therapies do not work nearly as well as ACTH or other standard treatments,” Dr. Shellhaas said. “It is crucial to treat these infants with treatments that are effective.”

Dr. Shellhaas and her associates uncovered certain clinical factors associated with treatment selections. Among infants with unknown infantile spasm etiology, 30% were given nonstandard treatment, whereas 47% received ACTH. Infants who were not already on antiepileptic drugs more often received nonstandard therapies than ACTH (45% vs. 17%).

However, ACTH was still more likely to be given over nonstandard therapies to infants who had hypsarrhythmia (84% vs. 57%) or a normal head circumference (77% vs. 57%).

Dr. Shellhaas reported no relevant financial disclosures. The Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation funded the study.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: AES 2017 abstract 1.303

REPORTING FROM AES 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: If the infants who had received nonstandard therapies had instead received ACTH, their response rate would have improved from 5% to 32% (P less than .01).

Data source: Prospective study of 352 infants gathered from the National Infantile Spasms Consortium database from 2012-2016.

Disclosures: The presenter reported no relevant financial disclosures. The Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation funded the study.

Source: R. Shellhaas, et al. AES 2017 abstract 1.303

Fenfluramine trials in Dravet syndrome yield highly positive results

WASHINGTON – The oral experimental agent fenfluramine, also known as ZX008, has been associated with a high degree of efficacy and good tolerability for the adjunctive treatment of Dravet syndrome, according to combined results of the first patients enrolled in two phase III trials.

“For me, a highlight of this study is the finding that 45% of patients on the higher dose achieved at least a 75% reduction from baseline in monthly convulsive seizures. This is a life-changing improvement,” reported Joseph Sullivan, MD, director of the pediatric epilepsy center at the University of California, San Francisco. He presented the results at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“If fenfluramine is approved as an adjunctive agent, it is likely to be introduced as the second or third medication in an effort to gain adequate symptom control,” Dr. Sullivan speculated.

Three phase 3 trials with fenfluramine are underway. The data presented at the American Epilepsy Society meeting were based on the first 119 patients who had participated in either of the two identical trials conducted in Europe and North America. The data from these two trials has now been combined, and the outcomes in the remaining patients in these two trials will be presented at a later time along with results from a third phase 3 study.

Patients between the ages of 2 and 18 years with a clinical diagnosis of Dravet syndrome were eligible for the European and North American trials if they were not controlled on current therapy, which could include multiple agents. However, patients had to be on stable therapies prior to enrollment for at least 4 weeks. Once enrolled, they were observed for 6 weeks prior to randomization.

After randomization to placebo, 0.2 mg/kg fenfluramine, or 0.8 mg/kg fenfluramine, patients completed a 2-week titration before they reached their maintenance dose. They were then evaluated over an additional 12-week treatment period. There were three withdrawals over the course of treatment in the placebo group, none in the lower-dose fenfluramine group, and six in the higher-dose fenfluramine group.

The primary endpoint was change in mean monthly convulsive seizure frequency from the observation period. When compared with placebo, these reductions were 63.9% (P less than .001) in the 0.8-mg/kg group and 33.7% (P = .019) in the 0.2-mg/kg group. When expressed as the median percent reduction in convulsive seizures from the observation period per 28 days, the reductions were 72.4% for the 0.8-mg/kg dose (P less than .001 vs. placebo), 37.6% for the 0.2-mg/kg group (P = .185 vs. placebo), and 17.4% for placebo.

Other efficacy measures supported the relative advantage of fenfluramine. For example, 70% and 41% of the patients in the 0.8-mg/kg and 0.2-mg/kg groups, respectively, versus 8% of placebo patients, had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency. Median seizure-free intervals for the three groups were 20.5, 14, and 9 days, respectively. Seizure activity was reduced to one or no seizures over the treatment period in 25% of the 0.8-mg/kg group, 12.8% of the 0.2-mg/kg group, and 0% of the placebo group.

The most common adverse events on the 0.8-mg/kg dose of fenfluramine, compared with placebo, were decreased appetite (37.5% vs. 5%) and lethargy (17.5% vs. 5%). The proportion of patients with weight loss was also greater on 0.8 mg/kg (5%) and 0.2 mg/kg (12.8%) versus placebo (0%). Diarrhea was more common in the 0.2-mg/kg group (30.8%) than in the 0.8-mg/kg group (17.5%) or in the placebo group (7.5%).

Although monitored closely, cardiotoxicity was not observed in this study. Concern about potential cardiotoxic effects was generated by the increased risk of valvular disease observed in patients taking fenfluramine with phentermine (fen-phen) for weight loss in the 1990s. This combination was withdrawn from the market in 1997.

“The potential for cardiotoxicity will continue to be monitored closely, but these initial results were reassuring,” reported Dr. Sullivan, who noted that a history of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease were exclusion criteria from this study.

Application for regulatory approval is not anticipated until all the phase 3 trial data are available, but Dr. Sullivan said that the results so far suggest that fenfluramine as an adjunctive agent “may represent a significant advance over existing treatment options for Dravet syndrome.”

The studies are funded by Zogenix. Dr. Sullivan reported financial relationships with Epygenix and Zogenix.

WASHINGTON – The oral experimental agent fenfluramine, also known as ZX008, has been associated with a high degree of efficacy and good tolerability for the adjunctive treatment of Dravet syndrome, according to combined results of the first patients enrolled in two phase III trials.

“For me, a highlight of this study is the finding that 45% of patients on the higher dose achieved at least a 75% reduction from baseline in monthly convulsive seizures. This is a life-changing improvement,” reported Joseph Sullivan, MD, director of the pediatric epilepsy center at the University of California, San Francisco. He presented the results at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“If fenfluramine is approved as an adjunctive agent, it is likely to be introduced as the second or third medication in an effort to gain adequate symptom control,” Dr. Sullivan speculated.

Three phase 3 trials with fenfluramine are underway. The data presented at the American Epilepsy Society meeting were based on the first 119 patients who had participated in either of the two identical trials conducted in Europe and North America. The data from these two trials has now been combined, and the outcomes in the remaining patients in these two trials will be presented at a later time along with results from a third phase 3 study.

Patients between the ages of 2 and 18 years with a clinical diagnosis of Dravet syndrome were eligible for the European and North American trials if they were not controlled on current therapy, which could include multiple agents. However, patients had to be on stable therapies prior to enrollment for at least 4 weeks. Once enrolled, they were observed for 6 weeks prior to randomization.

After randomization to placebo, 0.2 mg/kg fenfluramine, or 0.8 mg/kg fenfluramine, patients completed a 2-week titration before they reached their maintenance dose. They were then evaluated over an additional 12-week treatment period. There were three withdrawals over the course of treatment in the placebo group, none in the lower-dose fenfluramine group, and six in the higher-dose fenfluramine group.

The primary endpoint was change in mean monthly convulsive seizure frequency from the observation period. When compared with placebo, these reductions were 63.9% (P less than .001) in the 0.8-mg/kg group and 33.7% (P = .019) in the 0.2-mg/kg group. When expressed as the median percent reduction in convulsive seizures from the observation period per 28 days, the reductions were 72.4% for the 0.8-mg/kg dose (P less than .001 vs. placebo), 37.6% for the 0.2-mg/kg group (P = .185 vs. placebo), and 17.4% for placebo.

Other efficacy measures supported the relative advantage of fenfluramine. For example, 70% and 41% of the patients in the 0.8-mg/kg and 0.2-mg/kg groups, respectively, versus 8% of placebo patients, had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency. Median seizure-free intervals for the three groups were 20.5, 14, and 9 days, respectively. Seizure activity was reduced to one or no seizures over the treatment period in 25% of the 0.8-mg/kg group, 12.8% of the 0.2-mg/kg group, and 0% of the placebo group.

The most common adverse events on the 0.8-mg/kg dose of fenfluramine, compared with placebo, were decreased appetite (37.5% vs. 5%) and lethargy (17.5% vs. 5%). The proportion of patients with weight loss was also greater on 0.8 mg/kg (5%) and 0.2 mg/kg (12.8%) versus placebo (0%). Diarrhea was more common in the 0.2-mg/kg group (30.8%) than in the 0.8-mg/kg group (17.5%) or in the placebo group (7.5%).

Although monitored closely, cardiotoxicity was not observed in this study. Concern about potential cardiotoxic effects was generated by the increased risk of valvular disease observed in patients taking fenfluramine with phentermine (fen-phen) for weight loss in the 1990s. This combination was withdrawn from the market in 1997.

“The potential for cardiotoxicity will continue to be monitored closely, but these initial results were reassuring,” reported Dr. Sullivan, who noted that a history of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease were exclusion criteria from this study.

Application for regulatory approval is not anticipated until all the phase 3 trial data are available, but Dr. Sullivan said that the results so far suggest that fenfluramine as an adjunctive agent “may represent a significant advance over existing treatment options for Dravet syndrome.”

The studies are funded by Zogenix. Dr. Sullivan reported financial relationships with Epygenix and Zogenix.

WASHINGTON – The oral experimental agent fenfluramine, also known as ZX008, has been associated with a high degree of efficacy and good tolerability for the adjunctive treatment of Dravet syndrome, according to combined results of the first patients enrolled in two phase III trials.

“For me, a highlight of this study is the finding that 45% of patients on the higher dose achieved at least a 75% reduction from baseline in monthly convulsive seizures. This is a life-changing improvement,” reported Joseph Sullivan, MD, director of the pediatric epilepsy center at the University of California, San Francisco. He presented the results at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“If fenfluramine is approved as an adjunctive agent, it is likely to be introduced as the second or third medication in an effort to gain adequate symptom control,” Dr. Sullivan speculated.

Three phase 3 trials with fenfluramine are underway. The data presented at the American Epilepsy Society meeting were based on the first 119 patients who had participated in either of the two identical trials conducted in Europe and North America. The data from these two trials has now been combined, and the outcomes in the remaining patients in these two trials will be presented at a later time along with results from a third phase 3 study.

Patients between the ages of 2 and 18 years with a clinical diagnosis of Dravet syndrome were eligible for the European and North American trials if they were not controlled on current therapy, which could include multiple agents. However, patients had to be on stable therapies prior to enrollment for at least 4 weeks. Once enrolled, they were observed for 6 weeks prior to randomization.

After randomization to placebo, 0.2 mg/kg fenfluramine, or 0.8 mg/kg fenfluramine, patients completed a 2-week titration before they reached their maintenance dose. They were then evaluated over an additional 12-week treatment period. There were three withdrawals over the course of treatment in the placebo group, none in the lower-dose fenfluramine group, and six in the higher-dose fenfluramine group.

The primary endpoint was change in mean monthly convulsive seizure frequency from the observation period. When compared with placebo, these reductions were 63.9% (P less than .001) in the 0.8-mg/kg group and 33.7% (P = .019) in the 0.2-mg/kg group. When expressed as the median percent reduction in convulsive seizures from the observation period per 28 days, the reductions were 72.4% for the 0.8-mg/kg dose (P less than .001 vs. placebo), 37.6% for the 0.2-mg/kg group (P = .185 vs. placebo), and 17.4% for placebo.

Other efficacy measures supported the relative advantage of fenfluramine. For example, 70% and 41% of the patients in the 0.8-mg/kg and 0.2-mg/kg groups, respectively, versus 8% of placebo patients, had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency. Median seizure-free intervals for the three groups were 20.5, 14, and 9 days, respectively. Seizure activity was reduced to one or no seizures over the treatment period in 25% of the 0.8-mg/kg group, 12.8% of the 0.2-mg/kg group, and 0% of the placebo group.

The most common adverse events on the 0.8-mg/kg dose of fenfluramine, compared with placebo, were decreased appetite (37.5% vs. 5%) and lethargy (17.5% vs. 5%). The proportion of patients with weight loss was also greater on 0.8 mg/kg (5%) and 0.2 mg/kg (12.8%) versus placebo (0%). Diarrhea was more common in the 0.2-mg/kg group (30.8%) than in the 0.8-mg/kg group (17.5%) or in the placebo group (7.5%).

Although monitored closely, cardiotoxicity was not observed in this study. Concern about potential cardiotoxic effects was generated by the increased risk of valvular disease observed in patients taking fenfluramine with phentermine (fen-phen) for weight loss in the 1990s. This combination was withdrawn from the market in 1997.

“The potential for cardiotoxicity will continue to be monitored closely, but these initial results were reassuring,” reported Dr. Sullivan, who noted that a history of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease were exclusion criteria from this study.

Application for regulatory approval is not anticipated until all the phase 3 trial data are available, but Dr. Sullivan said that the results so far suggest that fenfluramine as an adjunctive agent “may represent a significant advance over existing treatment options for Dravet syndrome.”

The studies are funded by Zogenix. Dr. Sullivan reported financial relationships with Epygenix and Zogenix.

REPORTING FROM AES 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: For the highest dose, the mean reduction in convulsive seizure frequency was 63.9% (P less than .001) versus placebo over a 14-week treatment period.

Data source: An analysis of the first 119 patients with Dravet syndrome enrolled in two ongoing randomized, double-blind, multicenter, phase 3 trials.

Disclosures: The studies are funded by Zogenix. The presenter reported financial relationships with Epygenix and Zogenix.

Source: L Lagae et al. AES 2017 Abstract 2.434

Continuous bedside monitoring improved safety of intracranial stereotactic EEG

WASHINGTON – After a life-threatening event prompted a trial of continuous monitoring of patients during intracranial stereotactic electroencephalogram (EEG), the rate of adverse events and missed seizures went to zero, according to a single-center analysis presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

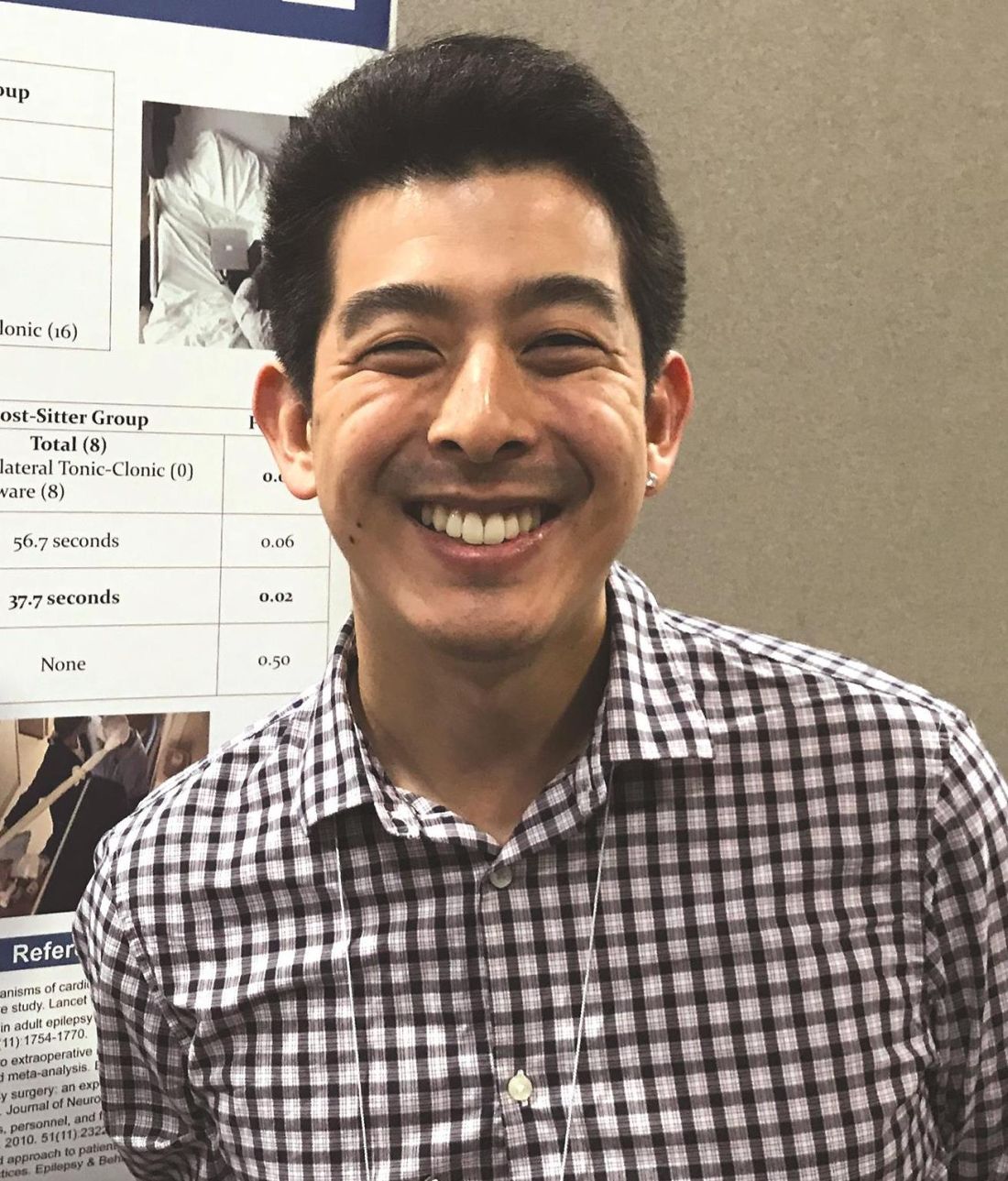

“After initiating a full-time, bedside sitter, none of the major events we saw in the presitter period, which included unrecognized tonic-clonic seizures or patient removal of electrodes, was observed,” reported Brad Kamitaki, MD, who is completing an epilepsy fellowship at Columbia University, New York.

Continuous observation of patients undergoing intracranial EEG has been described as mandatory in guidelines from the National Association of Epilepsy Centers (Epilepsia. 2010 Nov;51[11]:2322-33), but the type of monitoring, such as bedside sitter versus closed circuit video, has not been specified, according to Dr. Kamitaki. Although continuous bedside monitoring might offer the best opportunity to capture seizures and reduce the risk of adverse events, there are few comparative data.

In this study, the rate of adverse events was evaluated after a full-time, bedside sitter was initiated and compared with the rate observed prior to this step. There were 13 adult patients each in the presitter and sitter groups. All patients were admitted to an epilepsy unit for intracranial stereotactic EEG evaluation. Video monitoring by nursing staff was in place in the presitter period and continued to be active during the sitter periods.

There were 63 seizures captured in the presitter group and 53 in the sitter group. Of these, 21 were unrecognized in the presitter group versus 8 in the sitter group (P = .03). While most of the missed seizures were focal unaware in both groups (19 and 8, respectively), two focal-to-bilateral tonic-clonic seizures were missed in the presitter group versus zero in the sitter group.

In addition, there were two seizure-related adverse events in the presitter group versus none in the sitter group. Both of the adverse events, occurring in separate patients, were inappropriate electrode removals attributed to peri-ictal confusion during a focal unaware seizure. One required surgical reimplantation.

The greater mean time to nursing response after EEG onset of a seizure in the presitter group, compared with that of the sitter group, fell just short of statistical significance (77.1 vs. 56.7 seconds; P = .06), but the mean response time after clinical onset was significantly shorter in the sitter group (58.8 vs. 37.7 seconds; P = .02), according to Dr. Kamitaki.

Overall, the study “supports the likelihood that continuous bedside monitoring reduces the risk of adverse events,” Dr. Kamitaki said. “We did not look at what this costs, but concern about cost at our center was the reason that this program was not continued.”

A nursing assistant trained to recognize seizure activity performed the continuous bedside monitoring. The sitter remained beside the patient’s bed over a 24-hour period, leaving only if patient visitors obviated the need for a sitter. The monitoring was typically maintained over several days.

“Not all patients liked having a bedside sitter there at all times,” conceded Dr. Kamitaki, who acknowledged that other, less labor-intensive strategies might provide similar protection against adverse events. For example, a dedicated observer of multiple patients through video monitoring also might be effective, although formal studies are needed to evaluate how this compares with the current system of video monitors in a nursing station that do not have a dedicated observer.