(CVD). More severe TBI is associated with higher risk of CVD, new research shows.

Given the relatively young age of post-9/11–era veterans with TBI, there may be an increased burden of heart disease in the future as these veterans age and develop traditional risk factors for CVD, the investigators, led by Ian J. Stewart, MD, with Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Md., wrote.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

Novel data

Since Sept. 11, 2001, 4.5 million people have served in the U.S. military, with their time in service defined by the long-running wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Estimates suggest that up to 20% of post-9/11 veterans sustained a TBI.

While some evidence suggests that TBI increases the risk of CVD, prior reports have focused mainly on cerebrovascular outcomes. Until now, the potential association of TBI with CVD has not been comprehensively examined in post-9/11–era veterans.

The retrospective cohort study included 1,559,928 predominantly male post-9/11 veterans, including 301,169 (19.3%) with a history of TBI and 1,258,759 (81%) with no TBI history.

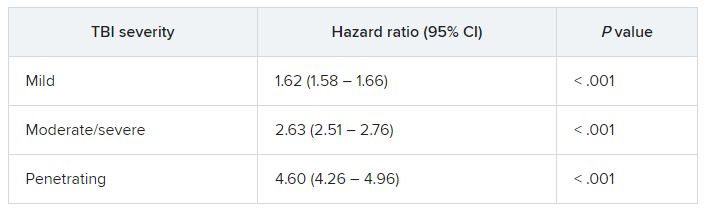

In fully adjusted models, compared with veterans with no TBI history, a history of mild, moderate/severe, or penetrating TBI was associated with increased risk of developing the composite CVD endpoint (coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, and CVD death).

TBIs of all severities were associated with the individual components of the composite outcome, except penetrating TBI and CVD death.

“The association of TBI with subsequent CVD was not attenuated in multivariable models, suggesting that TBI may be accounting for risk that is independent from the other variables,” Dr. Stewart and colleagues wrote.

They noted that the risk was highest shortly after injury, but TBI remained significantly associated with CVD for years after the initial insult.

Why TBI may raise the risk of subsequent CVD remains unclear.

It’s possible that patients with TBI develop more traditional risk factors for CVD through time than do patients without TBI. A study in mice found that TBI led to increased rates of atherosclerosis, the researchers said.

An additional mechanism may be disruption of autonomic regulation, which has been known to occur after TBI.

Another potential pathway is through mental health diagnoses, such as posttraumatic stress disorder; a large body of work has identified associations between PTSD and CVD, including among post-9/11 veterans.

Further work is needed to determine how this risk can be modified to improve outcomes for post-9/11–era veterans, the researchers write.

Unrecognized CVD risk factor?

Reached for comment, Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist and researcher from Boston who wasn’t involved in the study, said the effects of TBI on heart health are “very underreported, and most clinicians would not make the link.”

“When the brain suffers a traumatic injury, it activates a cascade of neuro-inflammation that goes haywire in an attempt to protect further brain damage. Oftentimes, these inflammatory by-products leak into the body, especially in trauma, when the barriers are broken between brain and body, and can cause systemic body inflammation, which is well associated with heart disease,” Dr. Lakhan said.

In addition, Dr. Lakhan said, “TBI itself localized to just the brain can negatively affect good health habits, leading to worsening heart health, too.”

“Research like this brings light where not much exists and underscores the importance of protecting our brains from physical trauma,” he said.

The study was supported by the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs, endorsed by the Department of Defense through the Psychological Health/Traumatic Brain Injury Research Program Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium, and by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Stewart and Dr. Lakhan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.