› Consider long-acting reversible contraception, such as an intrauterine device or an implant, as a first-line option for women who have mild or no symptoms of perimenopause. A

› Unless contraindicated, prescribe combination hormonal contraceptives for women in their 40s who desire them, as they are generally safe and effective in treating perimenopausal symptoms. A

› Use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s evidence-based recommendations to guide your choice of contraceptive for perimenopausal patients based on individual medical history. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

It is no secret that about half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended, and that teens have the highest rate of unplanned pregnancy. What’s not so well known is that women in their 40s have the second highest rate.1

Optimal use of contraception throughout perimenopause is crucial, but finding the right method of birth control for this patient population can be a bit of a balancing act. Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), such as an intrauterine device or progestin-only implant, are preferred first-line contraceptive options when preventing pregnancy is the primary goal, given their increased efficacy and limited number of contraindications.2,3 However, women experiencing perimenopausal symptoms often need a combination hormonal contraceptive (CHC)—typically an estrogen-containing pill, a patch, or a vaginal ring—for relief of vasomotor symptoms and cycle control.

Women in their 40s should have access to a full array of options to help improve adherence. However, physicians may be reluctant to prescribe estrogen-containing products for patients who often have a more complex medical history than their younger counterparts, including increased risks for breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

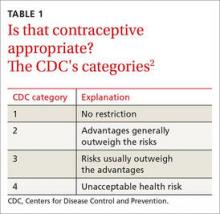

With this in mind, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified medical conditions that may affect the use of the various types of contraceptives by perimenopausal women and issued evidence-based recommendations on the appropriateness of each method using a one-to-4 rating system (TABLE 1).2 To help you address the contraceptive needs of such patients, we review the key risk factors, CDC guidelines, and optimal choices in the 4 case studies that follow.

CASE 1 › Sara G: VTE risk

Sara G, a healthy 45-year-old, recently started dating again following her divorce. She wants to avoid pregnancy. She has no personal or family history of clotting disorders and does not smoke. However, she is obese (body mass index [BMI]=32 kg/m2), and her job as a visiting nurse requires her to spend most of the day in her car. Ms. G also has acne and wants an estrogen-containing contraceptive to help treat it.

If Ms. G were your patient, what would you offer her?

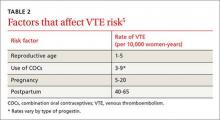

The risk for VTE increases substantially for women older than 40 years. In a recent cohort study, those ages 45 to 49 faced approximately twice the risk of women ages 25 to 29. However, the absolute risk for the older women was still low (4.7-5.3 per 10,000 woman-years).4 What’s more, the risk of VTE from the use of a CHC is substantially less than the risk associated with pregnancy and the postpartum period (TABLE 2).5

Obesity increases the risk. Women like Ms. G who are obese (BMI >30) have an increased risk for VTE associated with CHCs, but the CDC rates them as a Category 2 risk, even for obese women in their 40s—a determination that the advantages outweigh the risks.2

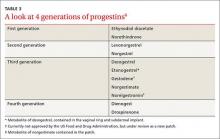

Progestin choice and estrogen dose matter. Combination oral contraceptives (COCs) that contain certain third-generation progestins (gestodene and desogestrel) may be more thrombophilic than those containing first- or second-generation progestins (TABLE 3).6 The relative risk (RR) for VTE with third-generation vs second-generation progestins is 1.3 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0-1.8).7 Formulations containing higher doses of estrogen are also more likely to be associated with VTE.7

Drospirenone is a newer progestin. Found in several COCs, drospirenone has antimineralocorticoid properties that help to minimize bloating and fluid retention but may also lead to a hypercoagulable state.5 Numerous studies have investigated the association between drospirenone and VTE risk, with conflicting results.8 Most recently, a large international prospective observational study involving more than 85,000 women showed no increased risk for VTE among women taking COCs with drospirenone compared with pills that do not contain this progestin.9

Non-oral CHCs, including the vaginal ring and the patch, offer the convenience of weekly or monthly use while providing similar benefits to COCs. Some fear that the continuous exposure to hormones associated with these methods may increase the risk for VTE, but evidence is mixed.