Case Reports

A platoon of 24 US Marines participated in a 1-week outdoor training exercise (February 4–8) at the Marine Corps Training Area Bellows in Oahu, Hawaii. During the last 3 days of training, 15 (62.5%) marines presented to the same primary care provider with what appeared to be diffuse scattered lesions on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands. All 15 patients reported that they noticed the lesions upon waking up the morning after their second night at the training area. The patients were unable to recollect specific direct arthropod interactions, but they reported the presence of “bugs” in the training area and denied use of any insect repellents, insect nets, or sunscreen. Sleeping arrangements varied from covered vehicles and cots to sleeping bags on the ground, which were laundered independently by each marine and thereby were ruled out as a commonality. The patients denied working with any chemicals or cleansers while in the field. Further questioning of all 15 patients revealed a history of extended contact with live foliage as branches were broken off to build camouflaged sites.

The following week, a second platoon of 20 marines occupied a separate undisturbed portion of the same training area for a similar 1-week training evolution. Manifestation of similar symptoms among members of the second group, who had no contact with the initial 15 patients, supported the likely environmental etiology of the eruptions.

| Figure 1. Numerous well-circumscribed, discrete, pink-red papules diffusely scattered across the face. |

| Figure 2. Papules with classic anemic halos. |

Referral

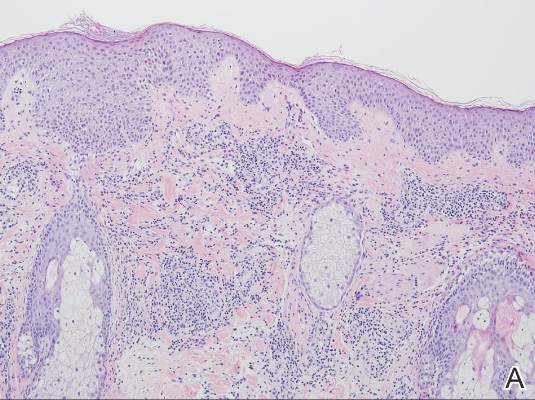

Two patients from the first group were evaluated at the dermatology clinic at Tripler Army Medical Center (Honolulu, Hawaii) on day 10 of the initial outbreak. Cutaneous examination revealed numerous discrete, pink-red, well-circumscribed, 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped papules exclusive to exposed areas on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands (Figures 1 and 2). Anemic halos surrounding the hand papules were noted (Figure 2). A punch biopsy in both patients revealed spongiotic dermatitis with superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic inflammation with eosinophils, suggestive of an arthropod bite (Figure 3). No retained arthropod parts wereidentified. Both patients were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily for 7 days with total resolution of the lesions.

Site Survey Results

Five days following the initial presentation of the first outbreak, a daytime site survey of the training area was conducted by a medical entomologist, an environmental health scientist, and a wildlife biologist. Records indicated that prior to the current utilization, the training area had not been used for 9 months. Approximately half of the training area was covered with mixed scrub vegetation and the remainder was clear pavement or sand (clear of vegetation). Feral hogs (Sus scrofa), cats (Felis domesticus), and mongooses (Herpestes javanicus) were observed at the site. Patient interviews and site survey ruled out a number of potential environmental irritants, including contact with fresh or salt water and chemical contaminants in the air or soil.

Because biting insects were suspected as the cause of the eruptions, an overnight entomological survey was conducted 3 weeks after the first outbreak under similar weather conditions and was centered in the area of an Australian pine (Casuarina equisetifolia) forest where most of the marines had slept during training. Mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus) were observed in the area, with an estimated biting rate of 1 to 2 bites per hour. Centipedes (Scolopendra subspinipes) were commonly observed after dark. There was no sign of heavy bird roosting or nesting, which would be a possible source of biting ectoparasites. Other than the Australian pine, notable vegetation present included Christmasberry (Schinus terebinthifolius), koa haole (Leucaena leucocephala), and Chinese banyan (Ficus microcarpa). A survey of the vegetation uncovered no notable insects, and no damage to the leaves of the Chinese banyans, which is typical of thrip infestation, was noted.

| Figure 3. Superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) with lymphocytic predominance (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). | |

After completion of a resource-intensive investigation that included site survey, literature review, detailed patient history including thrips-associated skin manifestations, and thorough consultation with local dermatologists and entomologists, the findings seemingly pointed to thrips as the most likely etiology of the eruption seen in our patients and a diagnosis of Thysanoptera dermatitis was made.

Comment

Thrips are small winged insects in the order Thysanoptera, which comprises more than 5000 identified species ranging in size from 0.5 to 15 mm, though most are approximately 1 mm.1 The insects typically are phytophagous (feeding on plants) and are attracted to humidity and seemingly the sweat of animals and humans.2 Although largely a phytophagous organism, a few published cases of thrips exposure reported papular skin eruptions known as Thysanoptera dermatitis.3-8 Several species of thrips across the globe have been associated with incidental attacks on humans to include “Heliothrips indicus Bagnall, a cotton pest of the Sudan; Thrips imagines Bagnall, reported in Australia; Limothrips cerealium (Haliday), in Germany; Gynaitkothrips uzeli Zimmerman, in Algeria; and other species.”7 In Hawaii, Gynaikothrips ficorum (Cuban laurel thrips) is a common pest of the Chinese banyan tree (F microcarpa) tree.9