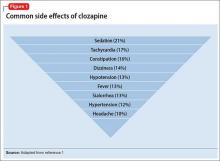

Clozapine is a highly effective antipsychotic with superior efficacy in treatment-resistant schizophrenia, but its side effect profile is daunting (Figure 1).1 Adverse reactions lead to approximately 17% of patients who take clozapine eventually discontinuing the medication.1 As we noted in Part 1 of this 3-part series,2 clozapine remains the most efficacious, but most tedious, antipsychotic available to psychiatrists because of its monitoring requirements and potential side effects.

A powerful rationale for prescribing clozapine, despite its drawbacks, is its association with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality.3,4 People with serious mental illness, including schizophrenia, have a median 10-year shorter life expectancy than the general population.5

A recent cohort study6 examined electronic health records to test whether intensive monitoring or lower suicide risk might account for the reduced mortality with clozapine. The authors found that the reduced mortality rate was not directly related to clozapine’s clinical monitoring or other confounding factors. They did find an association between clozapine use and reduced risk of death from both natural and unnatural causes.

This second article in our series examines clozapine’s adverse effects from a systems perspective. Severe neutropenia, myocarditis, sedation, weight gain, orthostatic hypotension, and sialorrhea appear to be the most studied adverse effects, but myriad others can occur.7 We offer guidance to help the astute clinician continue this effective antipsychotic by monitoring carefully, treating side effects early, and managing potential drug interactions (Table 1).8

Hematologic eventsSevere neutropenia, defined as absolute neutrophil count (ANC) <500/µL, is a well-known adverse effect of clozapine that requires specific clinical monitoring, a requirement that was updated by the FDA in 2015.2 The incidence of severe neutropenia peaks in the first 2 months of clozapine therapy and tapers after 6 months, but some risk always remains.

Older efficacy studies in the United States gauged the 1-year cumulative incidence of severe clozapine-induced neutropenia to be 2%.9 A 1998 study of the effects of using a clozapine registry reported a lower incidence—0.38%—than the 2% noted above.10 Early recognition and recommended interventions can improve clinical outcomes.2

Drug interactions and neutropenia. A retrospective study of mental health inpatients taking clozapine concurrently with oseltamivir during an influenza outbreak found a statistically significant—but not clinically significant—change in ANC values.11 The authors noted that viral infection might lead to blood dyscrasia early in illness, and that oseltamivir has been associated with a small incidence of blood dyscrasia.11-13 This information might be useful when treating influenza in patients taking clozapine, although no specific change in management is recommended.

Similarly, concomitant treatment with clozapine and lithium can affect both white blood cell and ANC values.14,15 Lithium-treated patients often demonstrate increased circulating neutrophils via enhancement of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor.16 Case studies describe how initiating lithium treatment enabled some patients to continue clozapine after developing neutropenia.14,17 Leukocytosis can affect blood monitoring, possibly masking other blood dyscrasias, when lithium is used concurrently with clozapine.

Eosinophilia (blood eosinophil count >700/µL) occurs in approximately 1% of clozapine users, usually in the first 4 weeks of treatment.18 It can be benign and transient or a harbinger of a more rare adverse reaction such as myocarditis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, colitis, or nephritis.19 If a patient taking clozapine develops eosinophilia, clozapine’s package insert recommends that you:

- evaluate promptly for other systemic involvement (rash, other evidence of allergic reaction, myocarditis, other organ-specific disease)

- stop clozapine immediately if any of these are found.

If other causes of eosinophilia are identified (asthma, allergies, collagen vascular disease, parasitic infection, neoplasm), treat these and continue clozapine.

The manufacturer also mentions the occurrence of clozapine-related eosinophilia without organ involvement that can resolve without intervention, with careful monitoring over several weeks.8 In this scenario, there is flexibility to judge whether clozapine should be stopped or re-challenged, or if close monitoring is adequate. Consulting with an internal medicine or hematology specialist might be helpful.

Cardiovascular side effectsMost common events. Three of the 10 most common clozapine side effects are cardiac: tachycardia, hypotension, and hypertension (Figure 1).1 Orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, and syncope also can occur, especially with rapid clozapine titration. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) can help differentiate whether abnormalities are clozapine-induced or related to a preexisting condition.

Reducing the dosage of clozapine or slowing titration could reverse cardiac side effects.8 If dosage reduction is not an option or is ineffective, first consider treating the side effect rather than discontinuing clozapine.20

Sinus tachycardia is one of the most common side effects of clozapine. First, rule out serious conditions—myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)—then consider waiting and monitoring for the first few months of clozapine treatment. If tachycardia continues, consider dosage reduction. Slower titration, or treatment with a cardio-selective beta blocker such as atenolol.21,22 Note that a recent Cochrane Review concluded that there is not enough randomized evidence to support any particular treatment for clozapine-induced tachycardia; the prescriber must therefore make a case-by-case clinical judgment.22