CASE › A 68-year-old woman with hypertension and hyperlipidemia comes into your office for evaluation of a 30-minute episode of sudden-onset right-hand weakness and difficulty speaking that occurred 4 days earlier. The patient, who is also a smoker, has come in at the insistence of her daughter. On examination, her blood pressure (BP) is 145/88 mm Hg and her heart rate is 76 beats/minute and regular. She appears well and her language function is normal. The rest of her examination is normal. How would you proceed?

Stroke—the death of nerve cells due to a lack of blood supply from either infarction or hemorrhage—strikes nearly 800,000 people in the United States every year.1,2 Of these events, 130,000 are fatal, making stroke the fifth leading cause of death.3 Effective, early evaluation and cause-specific treatment are crucial parts of stroke care.

Research has helped to clarify the critical role primary care physicians play in recognizing, triaging, and managing stroke and transient ischemic attacks (TIA). This article reviews what we know about the different ways that a stroke and a TIA can present, the appropriate diagnostic work-up for patients presenting with symptoms of either event, and management strategies for subacute care (24 hours to up to 14 days after a stroke has occurred).4,5 Unless otherwise specified, this review will focus on ischemic stroke because 87% of strokes are attributable to ischemia.1

A follow-up to this article on secondary stroke prevention will appear in the journal next month.

Look to onset more than type of symptoms for clues

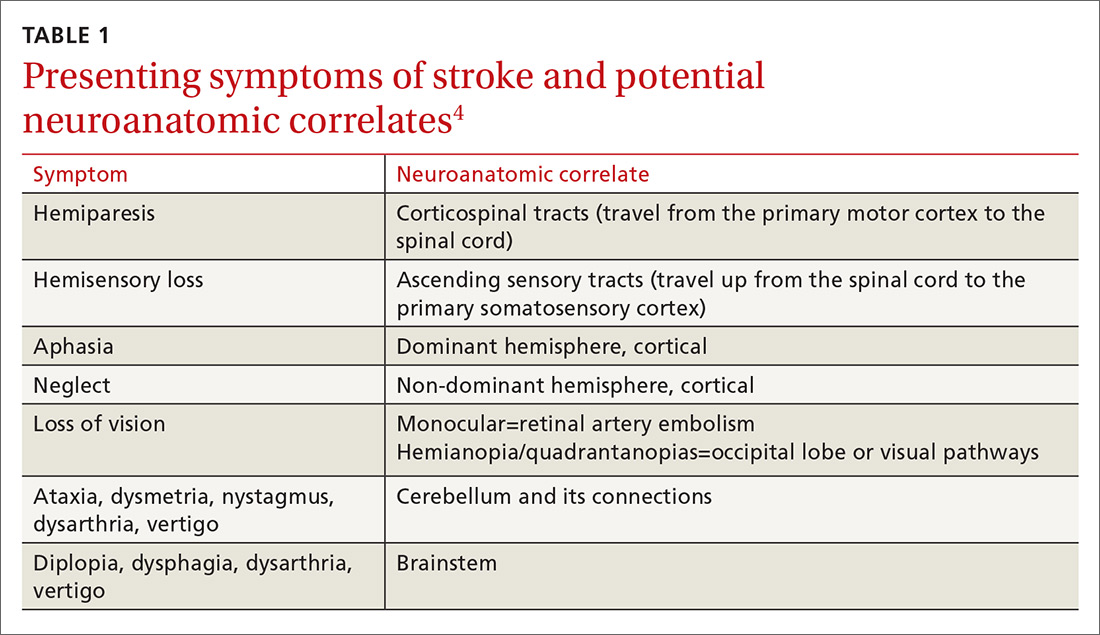

Stroke presents as a sudden onset of neurologic deficits (language, motor, sensory, cerebellar, or brainstem functions) (TABLE 14). Because presenting symptoms can vary widely, sudden onset, rather than particular symptoms, should raise a red flag for potential stroke.

The differential diagnosis includes: seizure, complex migraine, medication effect (eg, slurred speech or confusion after taking a central nervous system [CNS] depressant), toxin exposure, electrolyte abnormalities (especially hypoglycemia), concussion/trauma, infection of the CNS, peripheral vertigo, demyelination, intracranial mass, Bell’s palsy, and psychogenic disorders. The history and physical, along with laboratory findings and brain imaging (detailed later in this article), will guide the FP toward (or away from) these various etiologies.

Optimal triage is a subject of ongoing interest and research

If stroke or TIA remains a possibility after an initial assessment, it’s time to stratify patients by risk.

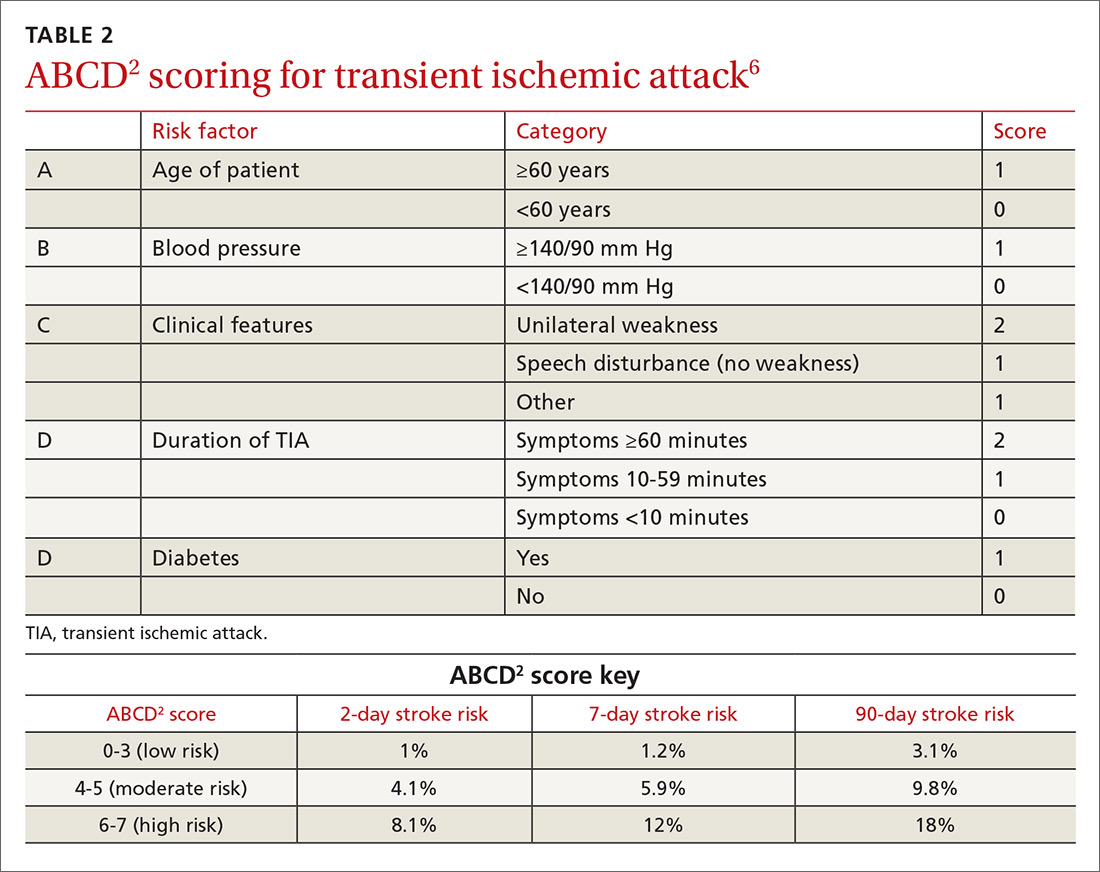

One of the most widely accepted tools is the ABCD2 score (see TABLE 26). Clinicians can employ the ABCD2 risk stratification tool when trying to determine whether it is reasonable to pursue an expedited work-up (ie, <1 day) in the outpatient setting or recommend that the patient be evaluated in an emergency department (ED). The 90-day stroke rate following a TIA ranges from 3% with an ABCD2 score of 0 to 3 to 18% with a score of 6 or 7. A score of 0 to 3 is considered relatively low risk; in the absence of other compelling factors, rapid outpatient evaluation is appropriate. For patients with an ABCD2 score ≥4, referral to the ED or direct admission to the hospital is advised.

The validity of the ABCD2 score for risk stratification has been studied extensively with conflicting results.7-10 As with any assessment tool, it should be used as a guide, and should not supplant a full assessment of the patient or the judgment of the examining physician. In making the decision regarding inpatient or outpatient evaluation, it’s also important to consider available resources, access to specialists, and patient preference.

In a 2016 population-based study, the 30-day recurrent stroke/TIA rate for patients hospitalized for TIA was 3% compared with 10.7% for those discharged from the ED with referral to a stroke clinic and 10.6% for those discharged from the ED without a referral to a stroke clinic.11 These data suggest that only patients for whom you have a low clinical suspicion of stroke/TIA should be worked up as outpatients, and that hospital admission is advised in moderate- and high-risk cases. The findings also highlight the critical role that primary care physicians can play in triaging and managing these patients for secondary prevention.

CASE › This patient’s recent history of sudden-onset right-sided weakness and expressive language dysfunction is suspicious for left hemispheric ischemia. She has several risk factors for stroke, and her ABCD2 score is 5 (hypertension, age ≥60 years, unilateral weakness, and duration 10-59 min), which places her at moderate risk. Thus, the recommendation would be to have her go directly to an ED for rapid evaluation.