Rectosigmoid endometriosis has been estimated to affect between 4% and 37% of patients with endometriosis and is one of the most advanced and complex forms of the disease. Bowel endometriosis can be asymptomatic but often involves severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and a spectrum of bowel symptoms such as dyschezia, diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and rectal bleeding. Deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis causes persistent or recurrent pain and is best treated by surgical removal of nodular lesions.

I have found that laparoscopic full-thickness disc resection (anterior discoid resection) with primary two-layer closure is often feasible and avoids the need for a complete bowel reanastomosis. It may not be an option in cases of multifocal rectal involvement (which may affect between one-quarter and one-third of patients with bowel endometriosis) or in cases involving large rectal nodules or luminal stenosis secondary to advanced fibrosis. In these cases, segmental bowel resection (low anterior resection) is often necessary. When anterior discoid resection is feasible, however, patients face significantly less morbidity with comparable outcomes.

Patients suspected of having invasive bowel disease are generally prepared through presurgical consultations with myself and my general surgeon colleague for the possibility of segmental resection; they understand that anterior discoid resection is often the goal but that the decision is ultimately determined intraoperatively.Less morbidity

Preoperative evaluation is far from straightforward, and practices vary. Transvaginal ultrasonography is used for diagnosing rectal endometriosis in select centers in certain regions of the world, but there are important limitations; not only is it highly operator dependent, but its limited range does not allow for the detection of endometriosis higher in the sigmoid colon. Endorectal ultrasonography can be an excellent tool for more fully evaluating rectal wall involvement, but it does not usually allow for the evaluation of disease elsewhere in the pelvis.

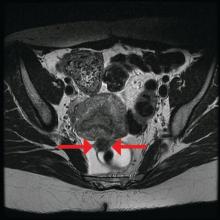

The preoperative tool we utilize most often along with clinical examination is MRI with vaginal and rectal contrast. MRI provides us with a superior anatomic perspective on the disease. Not only can we assess the depth of bowel wall infiltration and the distribution of the affected areas of the bowel, but we can see the bladder, the uterosacral ligaments, and how the uterus is situated relative to areas of disease. However, there are individualized limits to how high the contrast will travel, even with bowel preparation; disease that occurs significantly above the uterus often cannot be visualized as well as disease that occurs lower.

My general surgeon colleague and I have been working together for years, and we both are involved in counseling the patient suspected of having deep infiltrating disease. I typically talk with the patient about the probability of segmental resection based on my exam and preoperative MRI, and my colleague expands on this discussion with further explanation of the risks of bowel surgery.