My wife and I have traveled a number of times as far east as Kyrgyzstan and as far south as Paraguay to participate in short 1- to 2-week medical clinics. When I participated in a week-long medical clinic in Haiti in early 2017, the CEO of the hosting U.S. organization asked, “I wonder if we are doing any good here?” His organization had been to Onaville, Haiti for the last 4-5 years.

So my wife Stacy, a retired licensed practical nurse, and I, a general pediatrician with an interest in severe acute malnutrition, went on a 3-month medical sabbatical to Onaville. We were self-funded, with the exception of our home church in Senoia, Ga., paying the cost of our lodging during that time.

Prior to the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the government planned Onaville to be a retirement community area, with a population of only about 1,500, I was told. After the devastating temblor, it became one of several areas where the government sent people displaced from Port-au-Prince. The population today is possibly 250,000 or more.

The poverty in this area has “newer” flavor than areas such as Cité Soleil, which has been there for decades. What we found in Onaville – and probably all of Haiti – is an appalling lack of understanding and appreciation about the nature of malnutrition.

Methods and materials for study

The 1981 World Health Organization’s last printed monograph about severe acute nutrition remains essentially today’s cookbook recipe for treatment. Little seems to have changed since then in the literature I’ve reviewed. It didn’t take long after we started seeing the children in Onaville to shift that interest to something much more serious and widespread.

I wanted to start with basic health assessments in the Onaville children around 5 years and under. These children rarely see a physician, and only about half or so get any vaccine. Most parents do not have any immunization records in their possession to even review.

We decided to measure head size, mid-upper arm circumference, height, weight, and hemoglobin levels. Date of birth was recorded, if known or could at best be closely estimated. Vaccination was recorded as a yes or no response. All children also were examined for evidence of things like swelling, marasmic appearance (wasting, loss of body fat and muscle), yellowed hair, eye findings of vitamin A deficiency, etc. I wanted to get some impression about the health of these children in the same way that most mobile medical clinics do in Haiti.

Being a database programmer since I bought my first computer in 1985, and having written and deployed my office’s current EMR system in 2000, I decided before ever arriving in Haiti to write the software needed for this task. Unlike regular office EMRs, there were some special considerations.

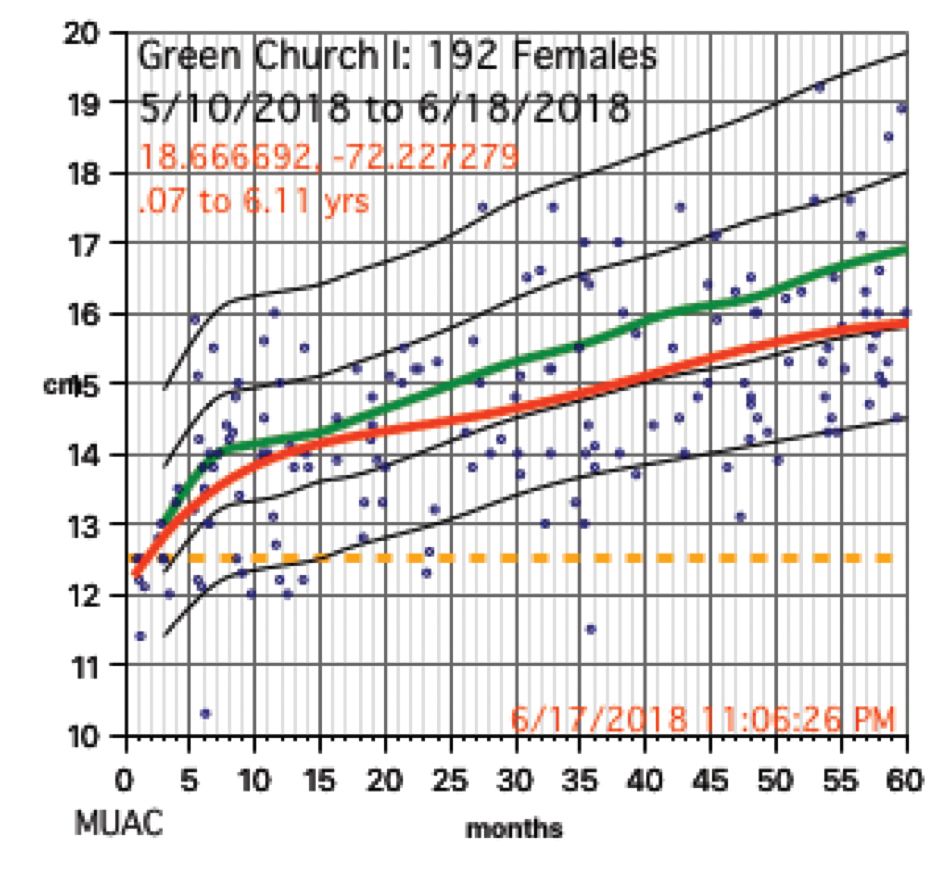

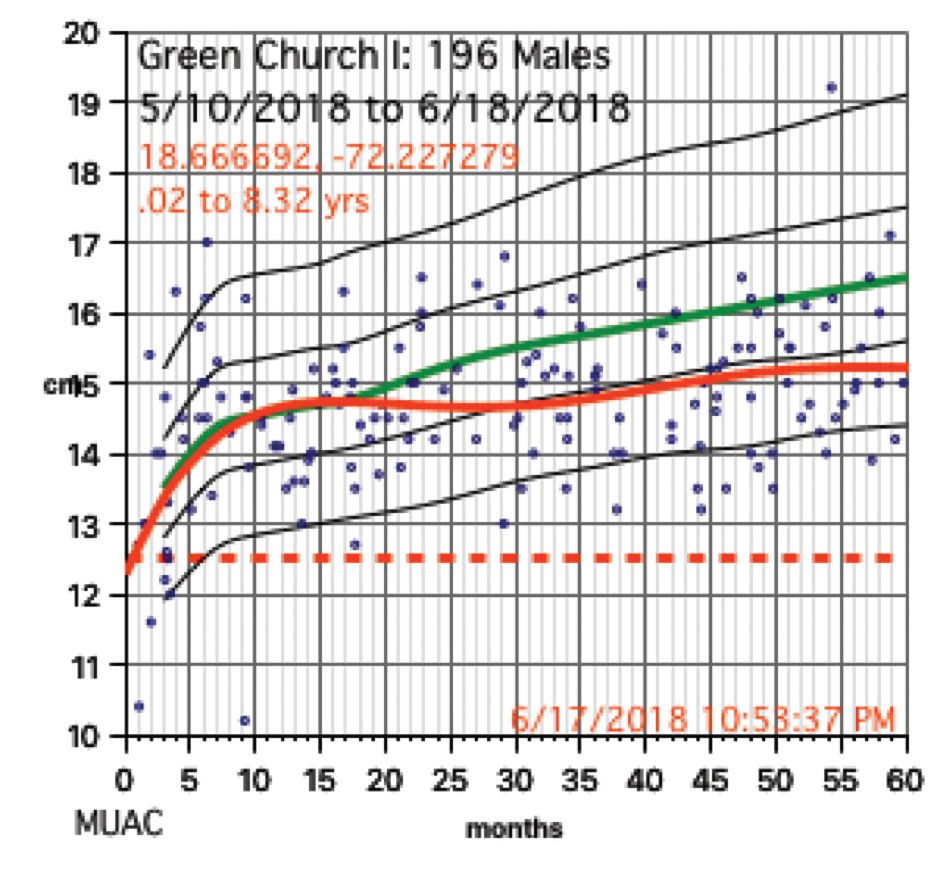

Growth charts needed not only to be generated for individuals, but in aggregate. Hemoglobins levels, too, needed charting. While in the United States, I use Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth chart data, but for Haiti I used WHO growth data. I was able to procure hemoglobin charting data as well. Aggregate data turned out to be key to our conclusions.

We used a regular consumer quality digital bathroom scale for weights. A sewing tape attached with duct tape to a wall or pillar was used to measure height. Standard head circumference tapes were use to measure heads and arms.

The hemoglobin was measured with a HemoCue Hb 201+ instrument. Size, ruggedness, and cost dictated all our choices because, except for food, we had to carry everything with us. The cost of a new HemoCue was under $400 and each microcuvette test was about $1.50.