Human trafficking (HT) is a secretive, multibillion dollar criminal industry involving the use of coercion, threats, and fraud to force individuals to engage in labor or commercial sex acts. In 2017, the International Labour Organization estimated that 24.9 million people worldwide were victims of forced labor (ie, working under threat or coercion).1 Risk factors for individuals who are vulnerable to HT include recent migration, substance use, housing insecurity, runaway youth, and mental illness. Traffickers continue the cycle of HT through isolation and emotional, physical, financial, and verbal abuse.

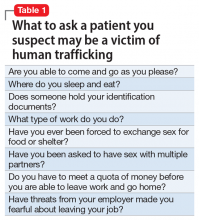

Survivors of HT may avoid seeking health care due to cultural reasons or feelings of guilt, isolation, distrust, or fear of criminal sanctions. There can be missed opportunities for victims to obtain help through health care services, law enforcement, child welfare services, or even family or friends. In a study of 173 survivors of HT in the United States, 68% of those who were currently trafficked visited with a health care professional at least once and were not identified as being trafficked.2 Psychiatrists rarely receive education on HT, which can lead to missed opportunities for identifying victims. Table 1 lists screening questions psychiatrists can ask patients they suspect may be trafficked.

The psychiatric sequelae of trafficking

Survivors of HT commonly experience psychiatric illness, substance use, pain, sexually transmitted diseases, and unplanned pregnancies.3 Here we discuss some of the psychiatric conditions that are common among HT survivors, and outline a multidisciplinary approach to their care.

PTSD, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Studies suggest survivors of HT who seek care have a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3 Survivors may have experienced multiple repetitive trauma, such as physical and sexual abuse.3 Compared with survivors of forced labor trafficking, survivors of sex trafficking have higher rates of childhood abuse, violence during trafficking, severe symptoms of PTSD, and comorbid depression and PTSD.4 For survivors with PTSD, consider psychosocial interventions that address social support, coping strategies, and community reintegration.5 Survivors can also benefit from trauma-informed care that focuses on the cognitive aspect of the trauma, such as cognitive processing therapy, which involves cognitive restructuring without a written account of the trauma.6

Substance use disorders. Some individuals who are trafficked may be forced to use drugs of abuse or alcohol, while others may use substances to help cope while they are being trafficked or afterwards.3 For these patients, motivational interviewing may be beneficial. Also, consider referring them to detoxification or rehabilitation programs.

Suicide and self-harm. In a study of 98 HT survivors in England, 33% reported a history of self-harm before receiving care and 25% engaged in self-harm during care.7 After engaging in self-harm, survivors of HT were more likely to be admitted to psychiatric inpatient units than were patients who had not been trafficked.7 It is crucial to conduct a suicide risk assessment as part of the trauma-informed care of these patients.

Other conditions. In addition to psychiatric illness, survivors of HT may experience physical symptoms such as headache, back pain, stomach pain, fatigue, dizziness, memory problems, and weight loss.3 Referral to other specialties may be necessary for addressing any of the patient’s other conditions.

Continue to: Use a multidisciplinary approach