As the population of older adults rises, primary osteoporosis has become a problem of public health significance, resulting in more than 2 million fractures and $19 billion in related costs annually in the United States.1 Despite the availability of effective primary and secondary preventive measures, many older adults do not receive adequate information on bone health from their primary care provider.2 Initiation of osteoporosis treatment is low even among patients who have had an osteoporotic fracture: Fewer than one-quarter of older adults with hip fracture have begun taking osteoporosis medication within 12 months of hospital discharge.3

In this overview of osteoporosis care, we provide information on how to evaluate and manage older adults in primary care settings who are at risk of, or have been given a diagnosis of, primary osteoporosis. The guidance that we offer reflects the most recent updates and recommendations by relevant professional societies.1,4-7

The nature and scope of an urgent problem

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mass and deterioration of bone structure that causes bone fragility and increases the risk of fracture.8 Operationally, it is defined by the World Health Organization as a bone mineral density (BMD) score below 2.5 SD from the mean value for a young White woman (ie, T-score ≤ –2.5).9 Primary osteoporosis is age related and occurs mostly in postmenopausal women and older men, affecting 25% of women and 5% of men ≥ 65 years.10

An osteoporotic fracture is particularly devastating in an older adult because it can cause pain, reduced mobility, depression, and social isolation and can increase the risk of related mortality.1 The National Osteoporosis Foundation estimates that 20% of older adults who sustain a hip fracture die within 1 year due to complications of the fracture itself or surgical repair.1 Therefore, it is of paramount importance to identify patients who are at increased risk of fracture and intervene early.

Clinical manifestations

Osteoporosis does not have a primary presentation; rather, disease manifests clinically when a patient develops complications. Often, a fragility fracture is the first sign in an older person.11

A fracture is the most important complication of osteoporosis and can result from low-trauma injury or a fall from standing height—thus, the term “fragility fracture.” Osteoporotic fractures commonly involve the vertebra, hip, and wrist. Hip and extremity fractures can result in limited or lost mobility and depression. Vertebral fractures can be asymptomatic or result in kyphosis and loss of height. Fractures can give rise to pain.

Age and female sexare risk factors

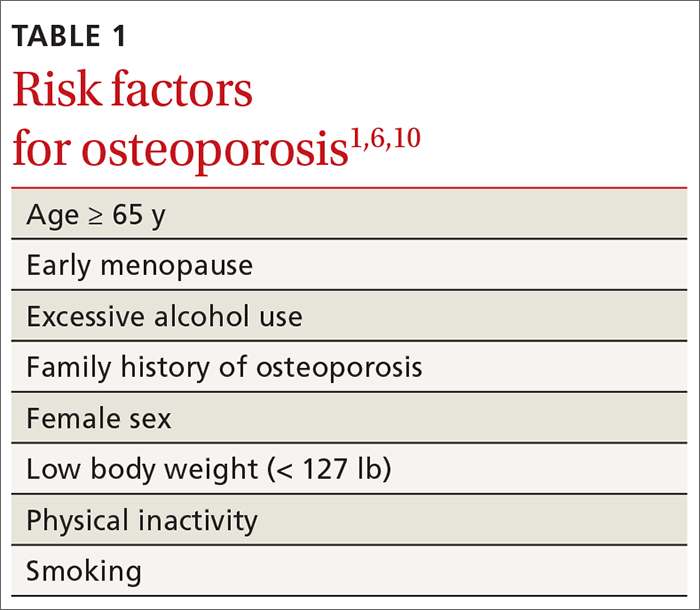

TABLE 11,6,10 lists risk factors associated with osteoporosis. Age is the most important; prevalence of osteoporosis increases with age. Other nonmodifiable risk factors include female sex (the disease appears earlier in women who enter menopause prematurely), family history of osteoporosis, and race and ethnicity. Twenty percent of Asian and non-Hispanic White women > 50 years have osteoporosis.1 A study showed that Mexican Americans are at higher risk of osteoporosis than non-Hispanic Whites; non-Hispanic Blacks are least affected.10

Other risk factors include low body weight (< 127 lb) and a history of fractures after age 50. Behavioral risk factors include smoking, excessive alcohol intake (> 3 drinks/d), poor nutrition, and a sedentary lifestyle.1,6

Continue to: Who should be screened?...