THE CASE

A 75-year-old man with a history of osteoarthritis presented to our clinic with worsening weakness over the previous month. His signs and symptoms included profound fatigue, subjective fevers, a 10-pound weight loss, ankle swelling, myalgias in his legs and back, shortness of breath, and a persistent cough. The patient was otherwise previously healthy.

The patient’s heart and lung exams were normal. Initial outpatient labs showed significantly elevated inflammatory markers, with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 102 mm/h (normal range for men ≥ 50 years, 0-20 mm/h) and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 11.1 mg/L (normal range, < 3 mg/L). The patient also had an elevated white blood cell count of 12,000/mcL (normal range, 4500-11,000/mcL). His hemoglobin was low (11 g/dL; normal range, 13.5-17.5 g/dL) and so was his albumin level (2.9 g/dL; normal range, 3.4-5.4 g/dL). The results of his prostate-specific antigen and brain natriuretic peptide tests were both normal. The results of a computed tomography scan of his thorax, abdomen, and pelvis were negative for malignancy.

The patient returned to our clinic 3 days later with severe weakness, which inhibited him from walking. He complained of a severe spasmodic pain between his shoulder blades. He denied joint stiffness, headaches, vision changes, or jaw claudication. The patient’s son had noted an overall increase in his father’s baseline heart rate, with readings increasing from the 50 beats/min range to the 70 beats/min range; this raised concern for a catecholamine-secreting tumor. There was also concern for occult infection and malignancy, or an autoimmune process, such as polymyalgia rheumatica. Due to his extreme weakness, the patient was directly admitted to the hospital for further work-up.

THE DIAGNOSIS

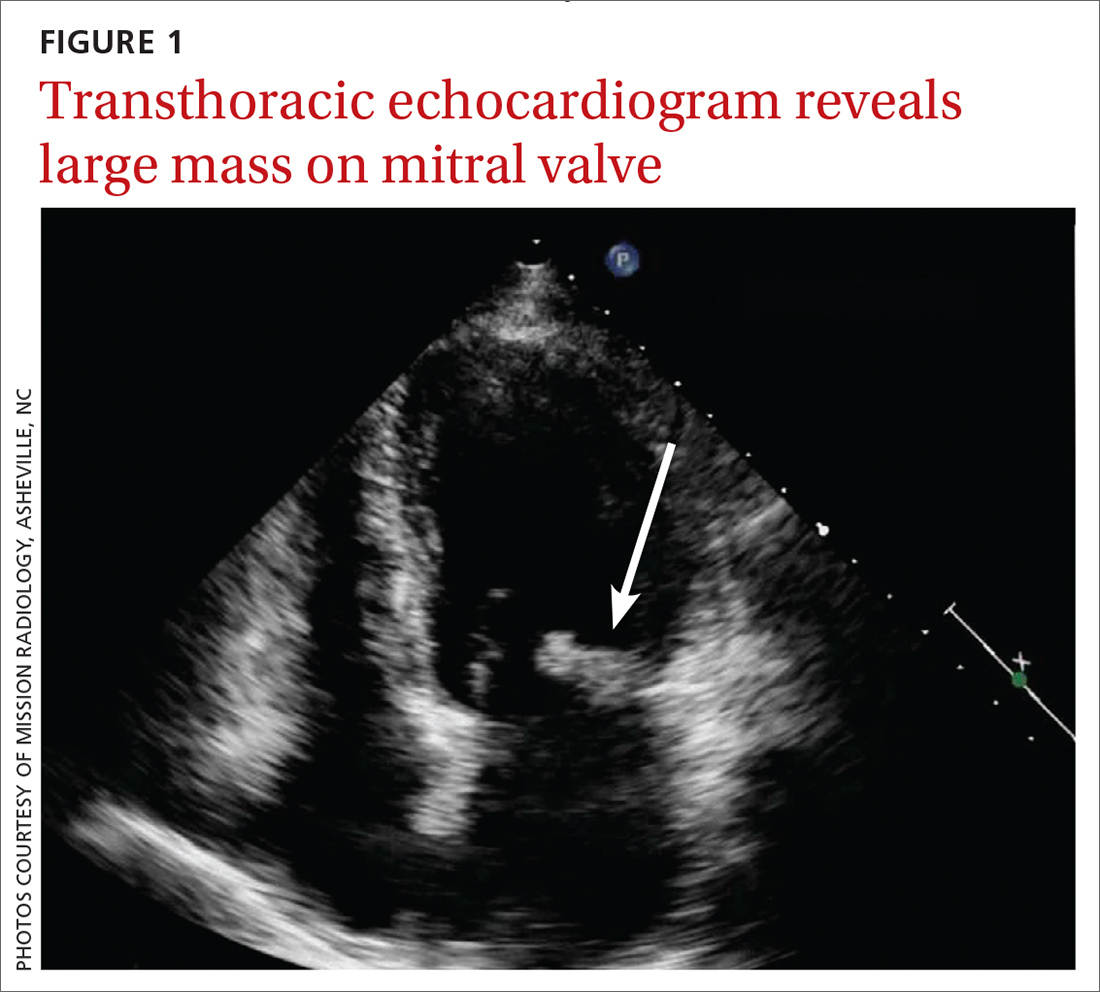

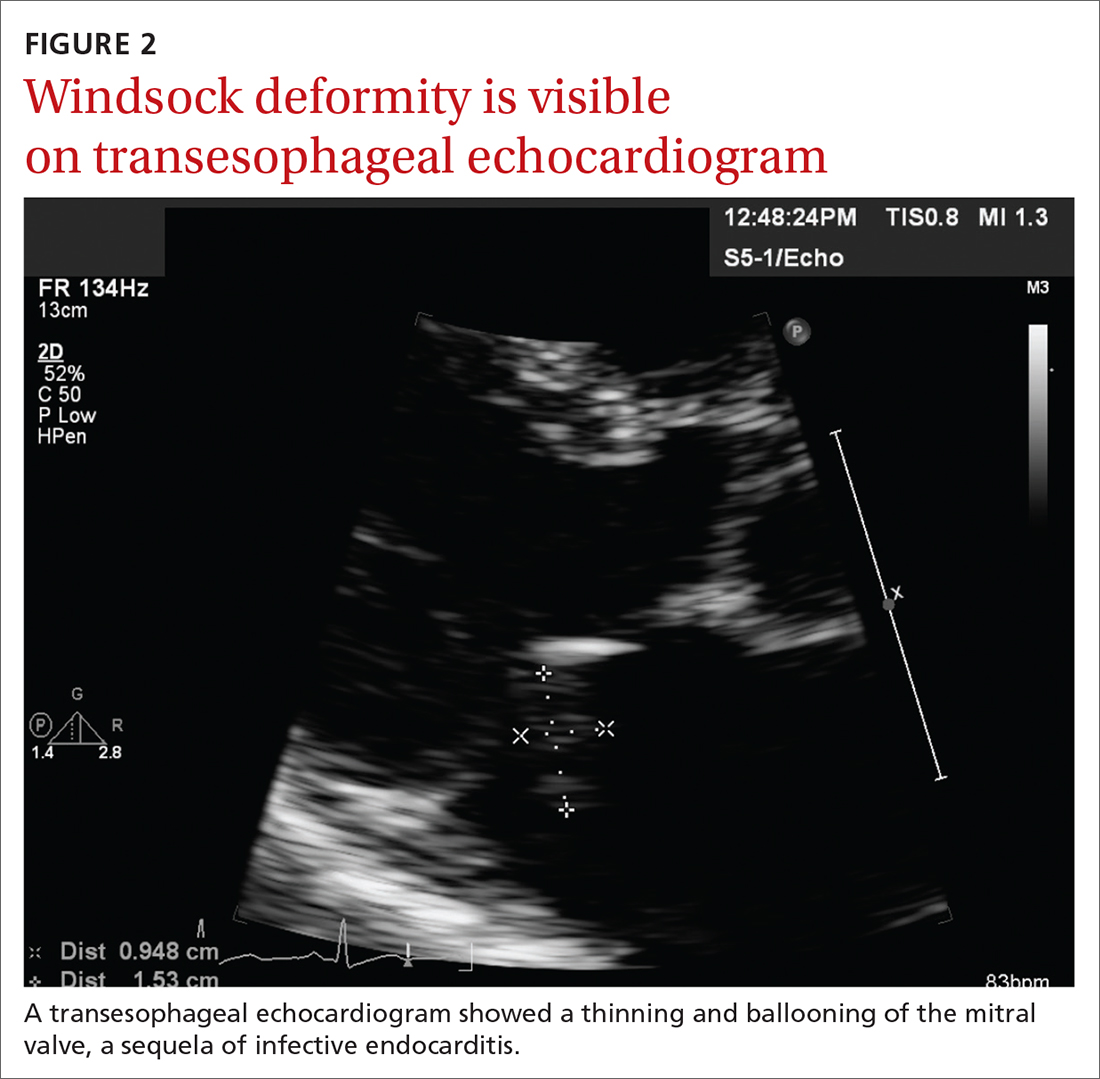

Concern for a smoldering infection prompted an order for a transthoracic echocardiogram. Images revealed a large mass on the mitral valve (FIGURE 1). Blood cultures quickly grew Streptococcus sanguinis. Additional work-up with a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) showed a “windsock” deformity (thinning and ballooning of the mitral valve), a known sequela of infective endocarditis (FIGURE 2).1 Further history obtained after the TEE revealed the patient had had a routine dental cleaning the month before his symptoms began. A murmur was then also detected.

DISCUSSION

Infective endocarditis (IE) is uncommon and difficult to diagnose; it has a high early-mortality rate of 30%.2 TEE is the recommended imaging study for IE, because it is more sensitive than a transthoracic echocardiogram for identifying vegetations on the valves and it is more cost effective.3

The modified Duke Criteria provide guidance for diagnosis of endocarditis. Major criteria focus on positive blood cultures and evidence of endocardial involvement. Minor criteria include predisposing heart conditions, intravenous drug use (IVDU), fever, and vascular and immunologic phenomena. As many as 90% of patients have a fever and often experience weight loss.4 Murmurs are auscultated in up to 85% of patients, and embolic features are present in up to 25% of patients at the time of diagnosis.4 In the developed world, Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, and splinter hemorrhages are increasingly rare, as patients usually present earlier in the disease course.4 While ESR and CRP are generally elevated in cases of IE, they are not part of the Duke Criteria.4

A closer look at risk factors

In 2007, guidelines for the prevention, treatment, and management of endocarditis were given significant categorical revision by the American Heart Association for the first time in 50 years.5 Recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures became more restrictive, to include only 4 groups of high-risk patients: those with prosthetic cardiac valves, those with a history of IE, those with congenital heart disease, and cardiac transplant recipients.4 The rationale for these restrictions included the small risk for anaphylaxis and potential increase in risk for bacterial resistance associated with antibiotic prophylaxis.4 A review published in 2021 noted no increase in the frequency of, nor the morbidity and mortality from, viridans group streptococcal IE since the guideline updates.5

Continue to: There is an emerging consensus...