CASE Patient inquires about new technology to detect cancer

A 51-year-old woman (para 2) presents to your clinic for a routine gynecology exam. She is up to date on her screening mammogram and Pap testing. She has her first colonoscopy scheduled for next month. She has a 10-year remote smoking history, but she stopped smoking in her late twenties. Her cousin was recently diagnosed with skin cancer, her father had prostate cancer and is now in remission, and her paternal grandmother died of ovarian cancer. She knows ovarian cancer does not have an effective screening test, and she recently heard on the news about a new blood test that can detect cancer before symptoms start. She would like to know more about this test. Could it replace her next Pap, mammogram, and future colonoscopies? She also wants to know—How can a simple blood test detect cancer?

The power of genomics in cancer care

Since the first human genome was sequenced in 2000, the power of genomics has been evident across many aspects of medicine, including cancer care.1 Whereas the first human genome to be sequenced took more than 10 years to sequence and cost over $1 billion, sequencing of your entire genome can now be obtained for less than $400—with results in a week.2

Genomics is now an integral part of cancer care, with results having implications for both cancer risk and prevention as well as more individualized treatment. For example, a healthy 42-year-old patient with a strong family history of breast cancer may undergo genetic testing and discover she has a mutation in the tumor suppression gene BRCA1, which carries a 39% to 58% lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.3 By undergoing a risk-reducing bilateral salpingooophorectomy she will lower her ovarian cancer risk by up to 96%.4,5 A 67-year-old with a new diagnosis of stage III ovarian cancer and a BRCA2 mutation may be in remission for 5+ years due to her BRCA2 mutation, which makes her eligible for the use of the poly(ADPribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib.6 Genetic testing as illustrated above has led to decreased cancer-related mortality and prolonged survival.7 However, many women with such germline mutations are faced with difficult choices about surgical risk reduction, with the potential harms of early menopause and quality of life concerns. Having a test that does not just predict cancer risk but in fact quantifies that risk for the individual would greatly help in these decisions. Furthermore, more than 75% of ovarian cancers occur without a germline mutation.

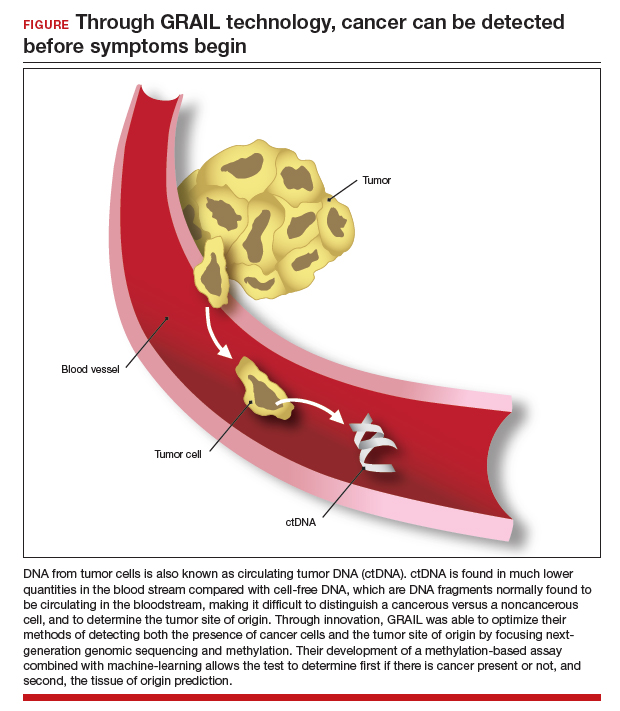

Advances in genetic testing technology also have led to the ability to obtain genetic information from a simple blood test. For example, cell-free DNA (cfDNA), which is DNA fragments that are normally found to be circulating in the bloodstream, is routinely used as a screening tool for prenatal genetic testing to detect chromosomal abnormalities in the fetus.8 This technology relies on analyzing fetal free (non-cellular) DNA that is naturally found circulating in maternal blood. More recently, similar technology using cfDNA has been applied for the screening and characterization of certain cancers.9 This powerful technology can detect cancer before symptoms begin—all from a simple blood test, often referred to as a “liquid biopsy.” However, understanding the utility, supporting data, and target population for these tests is important before employing them as part of routine clinical practice.

Continue to: Current methods of cancer screening are limited...