To the Editor:

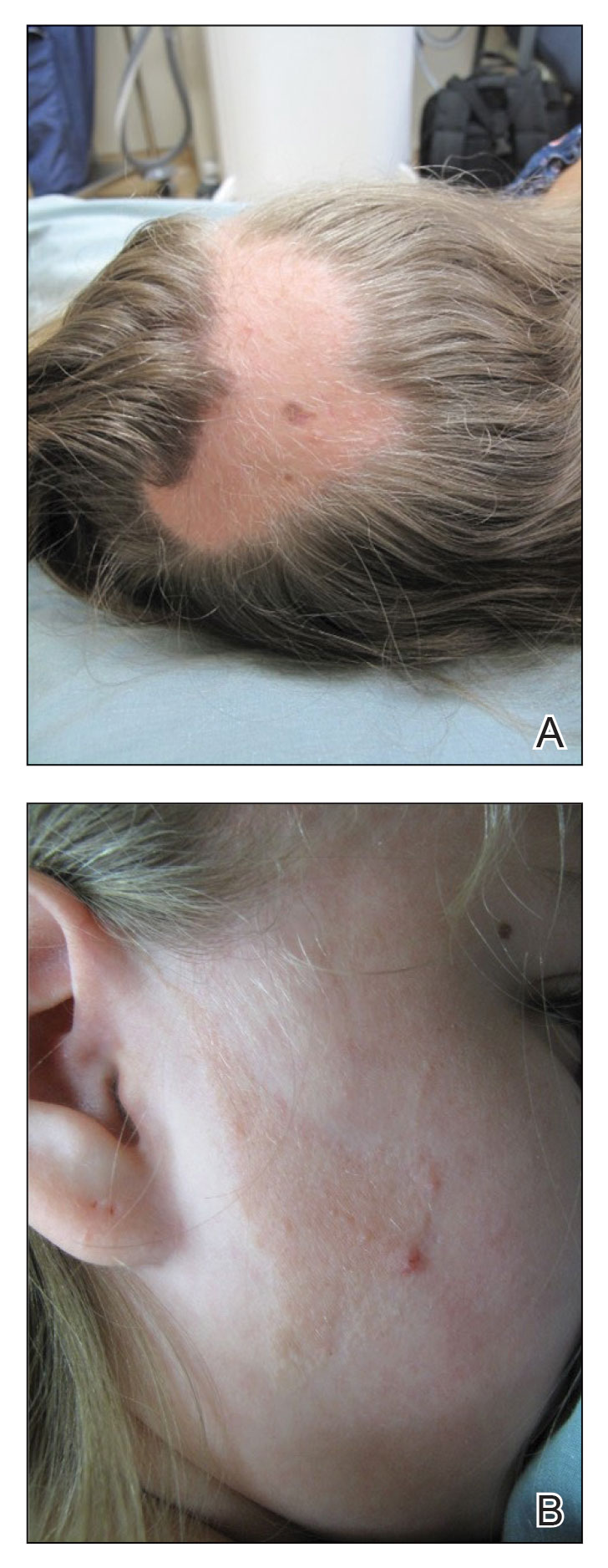

A 12-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a congenital scalp lesion. The patient was diagnosed with alopecia areata by a dermatologist at 4 years of age, and she was treated with topical corticosteroids and minoxidil, which failed to resolve her condition. Physical examination revealed an 8×10-cm, well-demarcated, yellowish-pink plaque located over the vertex and right parietal scalp (Figure 1A), extending down to the right preauricular cheek (Figure 1B) in a linear configuration with blaschkoid features. The scalp plaque appeared bald and completely lacking in terminal hairs but contained numerous fine vellus hairs (Figure 1A). A 6-mm, oval-appearing, pigmented papule was present in the plaque, and a few smaller, scattered, pigmented papules were noted in the vertex region (Figure 1A).

The cutaneous examination was otherwise unremarkable. A review of systems was negative, except for a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. There was no history of seizures or other neurocognitive developmental abnormalities.

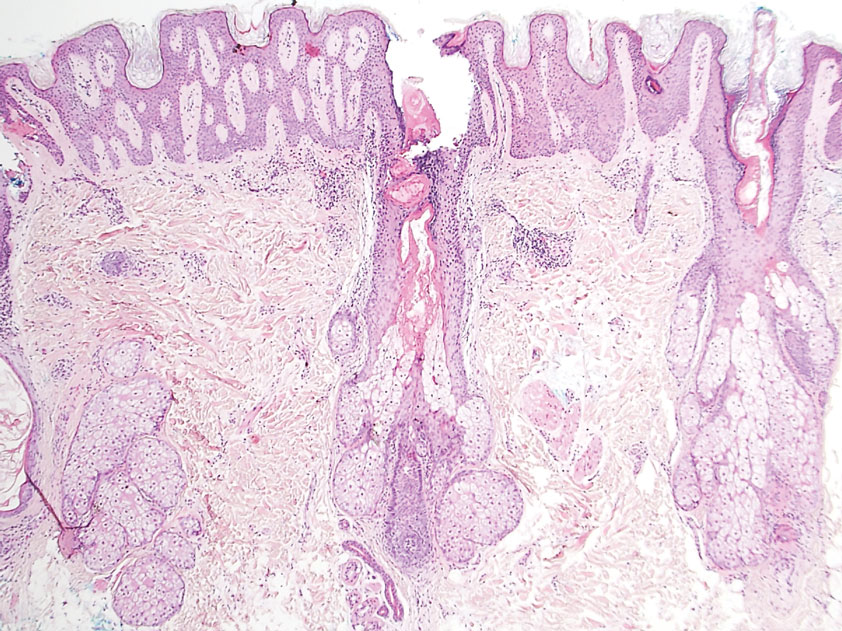

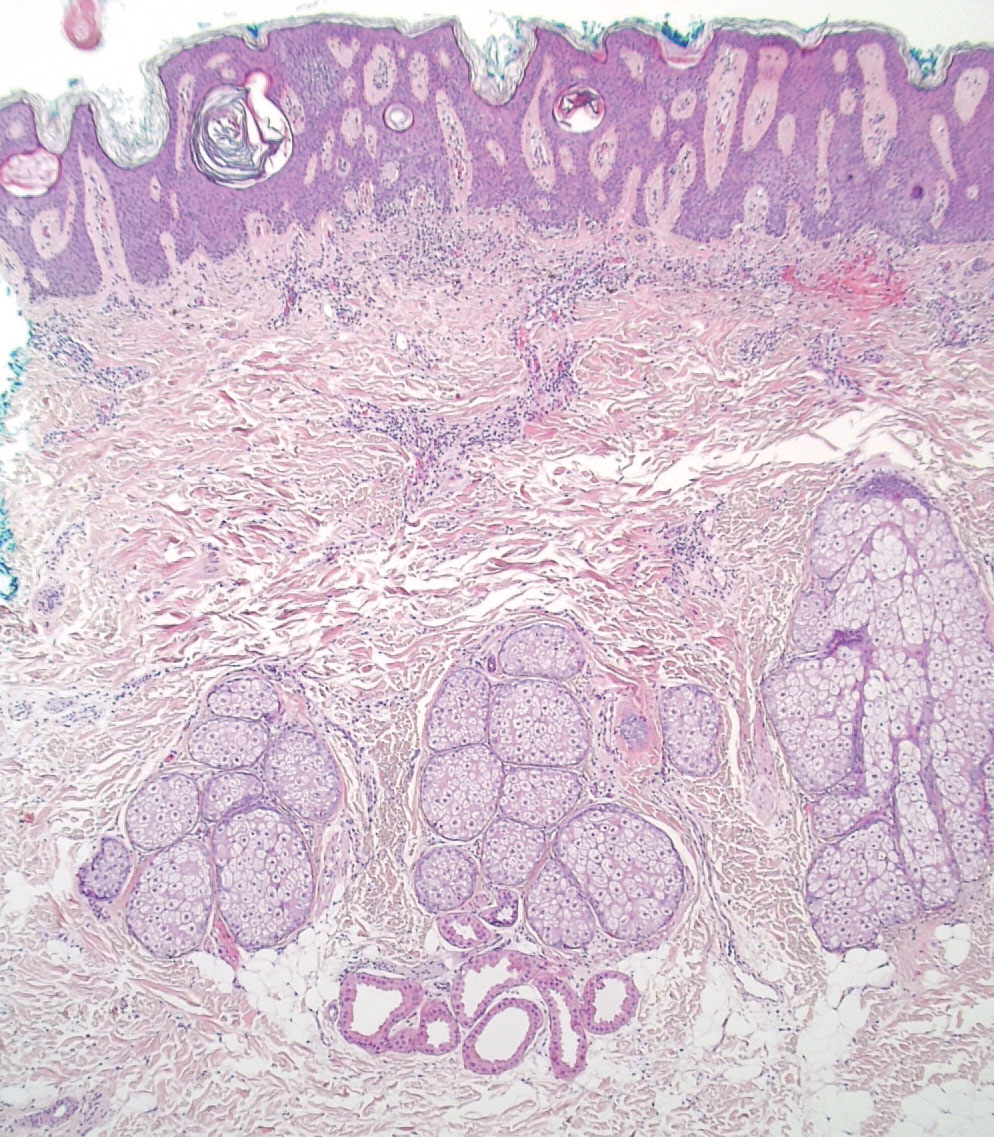

A 4-mm punch biopsy of the vertex scalp included the pigmented lesion but excluded an adnexal neoplasm. Epidermal acanthosis and mild papillomatosis were reported on microscopic examination. Multiple prominent sebaceous glands without associated hair follicles, which emptied directly onto the epidermal surface, were noted in the dermis (Figure 2). Several apocrine glands were observed (Figure 3). Epidermal and dermal melanocytic nests were highlighted with SOX-10 and Melan-A immunohistochemical stains, confirming the presence of a benign compound nevus. The punch biopsy analysis confirmed the diagnosis of a nevus sebaceus (NS) of Jadassohn (organoid nevus) with incidental compound nevus. Additional 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained for genetic testing, performed by the Genomics and Pathology Services at Washington University (St. Louis, Missouri). A missense HRAS p.G12V variant was observed in the tissue. A negative blood test result ruled out a germline mutation. The patient was managed with active observation of the lesion to evaluate for potential formation of neoplasms, as well as continuity of care with the dermatology clinic, considering the extent of the lesions, to monitor the development of any new medical conditions that would be concerning for syndromes associated with NS.

Nevus sebaceus is a benign skin hamartoma caused by a congenital defect in the pilosebaceous follicular unit and consists of epidermal, sebaceous, and apocrine elements.1,2 In dermatology patients, the prevalence of NS ranges from 0.05% to 1%.1 In 90% of cases, NS presents at birth as a 1- to 10-cm, round or linear, yellowish-orange, hairless plaque located on the scalp. It also may appear on the face, neck, trunk, oral mucosa, or labia minora.1,3 Although NS is a benign condition, secondary tumors may form within the lesion.3

The physical and histologic characteristics of NS evolve as the patient ages. In childhood, NS typically appears as a yellow-pink macule or patch with mild to moderate epidermal hyperplasia. Patients exhibit underdeveloped sebaceous glands, immature hair follicles, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis.1,3,4 The development of early lesions can be quite subtle and can lead to diagnostic uncertainty, as described in our patient. During puberty, lesions thicken due to papillomatous hyperplasia in the epidermis, and the number and size of sebaceous and apocrine glands increase.4 In adults, the risk for secondary tumor formation increases. These physical and histologic transformations, including secondary tumor formation, are thought to be stimulated by the action of postpubertal androgens.1

Nevus sebaceus is associated with both benign and malignant secondary tumor formation; however, fewer than 1% of tumors are malignant.1 In a retrospective analysis, Idriss and Elston5 (N=707) reported that 21.4% of patients with NS had secondary neoplasms; 18.9% of the secondary neoplasms were benign, and 2.5% were malignant. Additionally, this study showed that secondary tumor formation can occur in children, though it typically occurs in adults. Benign neoplasms were reported in 5 children in the subset aged 0 to 10 years and 10 children in the subset aged 11 to 17 years; 1 child developed a malignant neoplasm in the latter subset.5 The most common NS-associated benign neoplasms include trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Others include trichilemmoma, apocrine/eccrine adenoma, and sebaceoma.1 Nevus sebaceus–associated malignant neoplasms include basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, carcinosarcoma, and sebaceous carcinoma.3

Our patient was incorrectly diagnosed and treated for alopecia areata before an eventual diagnosis of NS was confirmed by biopsy. Additional genetic studies revealed a novel mutation in the HRAS gene, the most commonly affected gene in NS. The most common mutation location seen in more than 90% of NS lesions is HRAS c.37G>C (p.G13R), while KRAS mutations account for almost all the remaining cases.3 In our patient, a pathogenic missense HRAS p.G12V variant of somatic origin was detected with DNA extraction and sequencing from a fresh tissue sample acquired from two 4-mm punch biopsies performed on the lesion. The following genes were sequenced and found to be uninvolved: BRAF, FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, GNA11, GNAQ, KRAS, MAP3K3, NRAS, PIK3CA, and TEK. The Sanger sequencing method for comparative analysis performed on peripheral blood was negative.