Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)(PASH) syndrome is a recently identified disease process within the spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases (AIDs), which are distinct from autoimmune, infectious, and allergic syndromes and are gaining increasing interest given their complex pathophysiology and therapeutic resistance.1 Autoinflammatory diseases are defined by a dysregulation of the innate immune system in the absence of typical autoimmune features, including autoantibodies and antigen-specific T lymphocytes.2 Mutations affecting proteins of the inflammasome or proteins involved in regulating inflammasome function have been associated with these AIDs.2

Many AIDs have cutaneous involvement, as seen in PASH syndrome. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis presenting as skin ulcers with undermined, erythematous, violaceous borders. It can be isolated, syndromic, or associated with inflammatory conditions (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatologic disorders, hematologic disorders).1 Acne vulgaris develops because of chronic obstruction of hair follicles as a result of disordered keratinization and abnormal sebaceous stem cell differentiation.2 Propionibacterium acnes can reside and replicate within the biofilm community of the hair follicle and activate the inflammasome.2,3 Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic relapsing neutrophilic dermatosis, is a debilitating inflammatory disease of the hair follicles involving apocrine gland–bearing skin (ie, the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions).2 Onset often occurs between the ages of 20 and 40 years, with a 3-fold higher incidence in women compared to men.3 Patients experience painful, deep-seated nodules that drain into sinus tracts and abscesses. The condition can be isolated or associated with inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease.4

PASH syndrome has been described as a polygenic autoinflammatory condition that most commonly presents in young adults, with onset of acne beginning years prior to other manifestations. A study analyzing 5 patients with PASH syndrome reported an average age of 32.2 years at diagnosis with a disease duration of 3 to 7 years.5 Pathophysiology of this condition is not well understood, with many hypotheses calling upon dysregulation of the innate immune system, a commonality this syndrome may share with other AIDs. Given its poorly understood pathophysiology, treating PASH syndrome can be especially difficult. We report a novel case of disease remission lasting more than 4 years using adalimumab and cyclosporine. We also discuss prior treatment successes and hypotheses regarding etiologic factors in PASH syndrome.

Case Report

A 36-year-old woman presented for evaluation of open draining ulcerations on the back of 18 months’ duration. She had a 16-year history of scarring cystic acne of the face and HS of the groin. The patient’s family history was remarkable for severe cystic acne in her brother and son as well as HS in her mother and another brother. Her treatment history included isotretinoin, doxycycline, and topical steroids.

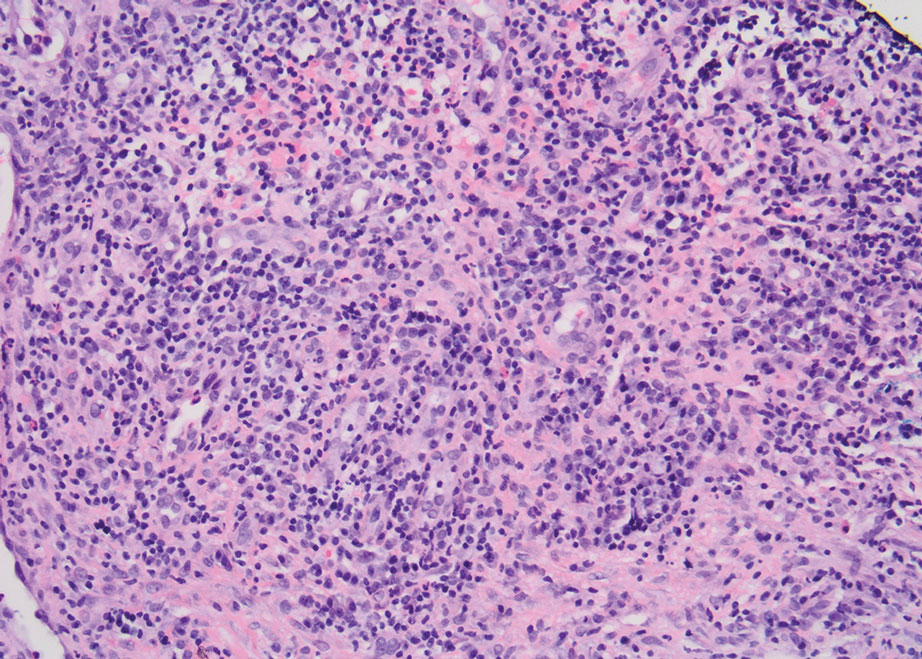

Physical examination revealed 2 ulcerations with violaceous borders involving the left upper back (greatest diameter, 5×7 cm)(Figure 1). Evidence of papular and cystic acne with residual scarring was noted on the cheeks. Scarring from HS was noted in the axillae and right groin. A biopsy from the edge of an ulceration on the back demonstrated epidermal spongiosis with acute and chronic inflammation and fibrosis (Figure 2). The clinicopathologic findings were most consistent with PG, and the patient was diagnosed with PASH syndrome, given the constellation of cutaneous lesions.

After treatment with topical and systemic antibiotics for acne and HS for more than 1 year failed, the patient was started on adalimumab. The initial dose was 160 mg subcutaneously, then 80 mg 2 weeks later, then 40 mg weekly thereafter. Doxycycline was continued for treatment of the acne and HS. After 6 weeks of adalimumab, the PG worsened and prednisone was added. She developed tender furuncles on the back, and cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus that responded to ciprofloxacin and cephalexin.

Due to progression of PG on adalimumab, switching to an infliximab infusion or anakinra was considered, but these options were not covered by the patient’s health insurance. Three months after the initial presentation, the patient was started on cyclosporine 100 mg 3 times daily (5 mg/kg/d) while adalimumab was continued; the ulcers started to improve within 2.5 weeks. After 3 months (Figure 3), the cyclosporine was reduced to 100 mg twice daily, and adalimumab was continued. She had a slight flare of PG after 8 months of treatment when adalimumab was unavailable to her for 2 months. After 8 months on cyclosporine, the dosage was tapered to 100 mg/d and then completely discontinued after 12 months.