Ms. K, age 32, presents to the psychiatric clinic for a routine follow-up. Her history includes agoraphobia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Ms. K’s current medications are oral hydroxyzine 50 mg 4 times daily as needed for anxiety and paliperidone palmitate 234 mg IM monthly. Since her last follow-up, she has been switched from oral sertraline 150 mg/d to oral paroxetine 20 mg/d. Ms. K reports having constipation (which improves by taking oral docusate 100 mg twice daily) and generalized hyperhidrosis. She wants to alleviate the hyperhidrosis without changing her paroxetine because that medication improved her symptoms.

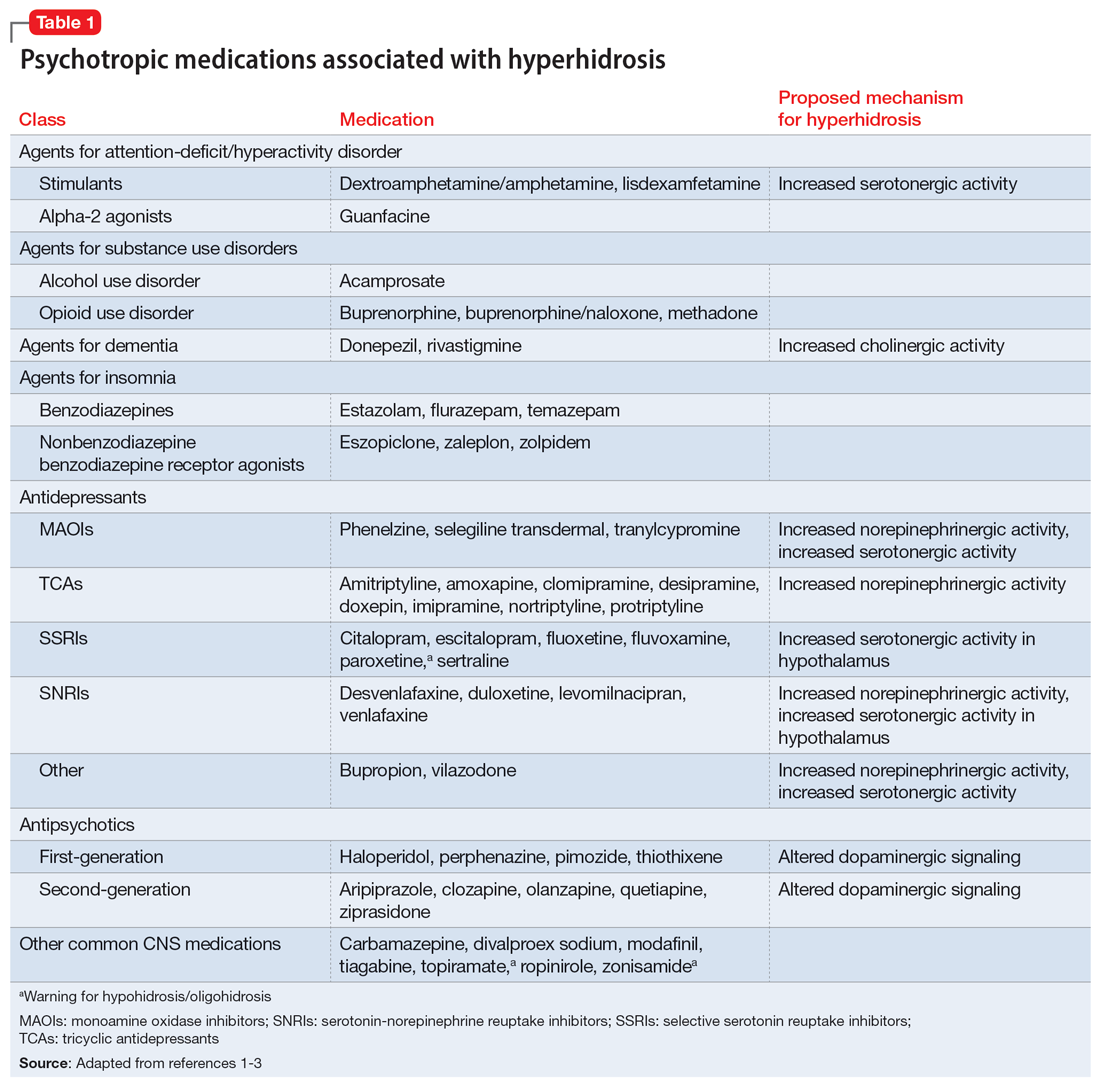

Hyperhidrosis—excessive sweating not needed to maintain a normal body temperature—is an uncommon and uncomfortable adverse effect of many medications, including psychotropics.1 This long-term adverse effect typically is not dose-related and does not remit with continued therapy.2 Table 11-3 lists psychotropic medications associated with hyperhidrosis as well as postulated mechanisms.

The incidence of medication-induced hyperhidrosis is unknown, but for psychotropic medications it is estimated to be 5% to 20%.3 Patients may not report hyperhidrosis due to embarrassment; in clinical trials, reporting measures may be inconsistent and, in some cases, misleading. For example, it is possible hyperhidrosis that appears to be associated with buprenorphine is actually a symptom of the withdrawal syndrome rather than a direct effect of the medication. Also, some medications, including certain psychotropics (eg, paroxetine4 and topiramate3) may cause either hyperhidrosis or hypohidrosis (decreased sweating). Few medications carry labeled warnings for hypohidrosis; the condition generally is not of clinical concern unless patients experience heat intolerance or hyperthermia.3

Psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis is likely an idiopathic effect. There are few known predisposing factors, but some medications carry a greater risk than others. In a meta-analysis, Beyer et al2 found certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline and paroxetine, had a higher risk of causing hyperhidrosis. Fluvoxamine, bupropion, and vortioxetine had the lowest risk. The class risk for SSRIs was comparable to that of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which all carried a comparable risk. In this analysis, neither indication nor dose were reliable indicators of risk of causing hyperhidrosis. However, the study found that for both SSRIs and SNRIs, increased affinity for the dopamine transporter was correlated with an increased risk of hyperhidrosis.2

Treatment

Treatment of hyperhidrosis depends on its cause and presentation.5 Hyperhidrosis may be categorized as primary (idiopathic) or secondary (also termed diaphoresis), and either focal or generalized.6 Many treatment recommendations focus on primary or focal hyperhidrosis and prioritize topical therapies.5 Because medication-induced hyperhidrosis most commonly presents as generalized3 and thus affects a large body surface area, the use of topical therapies is precluded. Topical therapy for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be pursued only if the patient’s sweating is localized.

Treating medication-induced hyperhidrosis becomes more complicated if it is not possible to alter the inciting medication (ie, because the medication is effective or the patient is resistant to change). In such scenarios, discontinuing the medication and initiating an alternative therapy may not be effective or feasible.2 For generalized presentations of medication-induced hyperhidrosis, if the inciting medication cannot be altered, initiating an oral systemic therapy is the preferred treatment.3,5

Oral anticholinergic medications (eg, benztropine, glycopyrrolate, and oxybutynin),4-6 act directly on muscarinic receptors within the eccrine sweat glands to decrease or stop sweating. They are considered first-line for generalized hyperhidrosis but may be inappropriate for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis because many psychotropics (eg, tricyclic antidepressants, paroxetine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and clozapine) have anticholinergic properties. Adding an anticholinergic medication to these patients’ regimens may increase the adverse effect burden and worsen cognitive deficits. Additionally, approximately one-third of patients discontinue anticholinergic medications due to tolerability issues (eg, dry mouth).

Continue to: However, anticholinergic medications...