Hysteroscopy is a crucial examination for the diagnosis of endometrial cancer. In Brazil, women with postmenopausal bleeding who need to undergo this procedure in the public health system wait in line alongside patients with less severe complaints. Until now, there has been no system to prioritize patients at high risk for cancer. But this situation may change, thanks to a Brazilian study published in February in the Journal of Clinical Medicine.

Researchers from the Municipal Hospital of Vila Santa Catarina in São Paulo, a public unit managed by Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, have developed the Endometrial Malignancy Prediction System (EMPS), a nomogram to identify patients at high risk for endometrial cancer and prioritize them in the hysteroscopy waiting list.

Bruna Bottura, MD, a gynecologist and obstetrician at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein and the study’s lead author, told this news organization that the idea to create the nomogram arose during the COVID-19 pandemic. “We noticed that ... when outpatient clinics resumed, we were seeing many patients for intrauterine device (IUD) removal. We thought it was unfair for a patient with postmenopausal bleeding, who has a chance of having cancer, to have to wait in the same line as a patient needing IUD removal,” she said. This realization motivated the development of the tool, which was overseen by Renato Moretti-Marques, MD, PhD.

The EMPS Score

The team conducted a retrospective case-control study involving 1945 patients with suspected endometrial cancer who had undergone diagnostic hysteroscopy at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein between March 2019 and March 2022. Among these patients, 107 were diagnosed with precursor lesions or endometrial cancer on the basis of biopsy. The other 1838 participants, who had had cancer ruled out by biopsy, formed the control group.

Through bivariate and multivariate linear regression analysis, the authors determined that the presence or absence of hypertension, diabetes, postmenopausal bleeding, endometrial polyps, uterine volume, number of pregnancies, body mass index, age, and endometrial thickness were the main risk factors for endometrial cancer diagnosis.

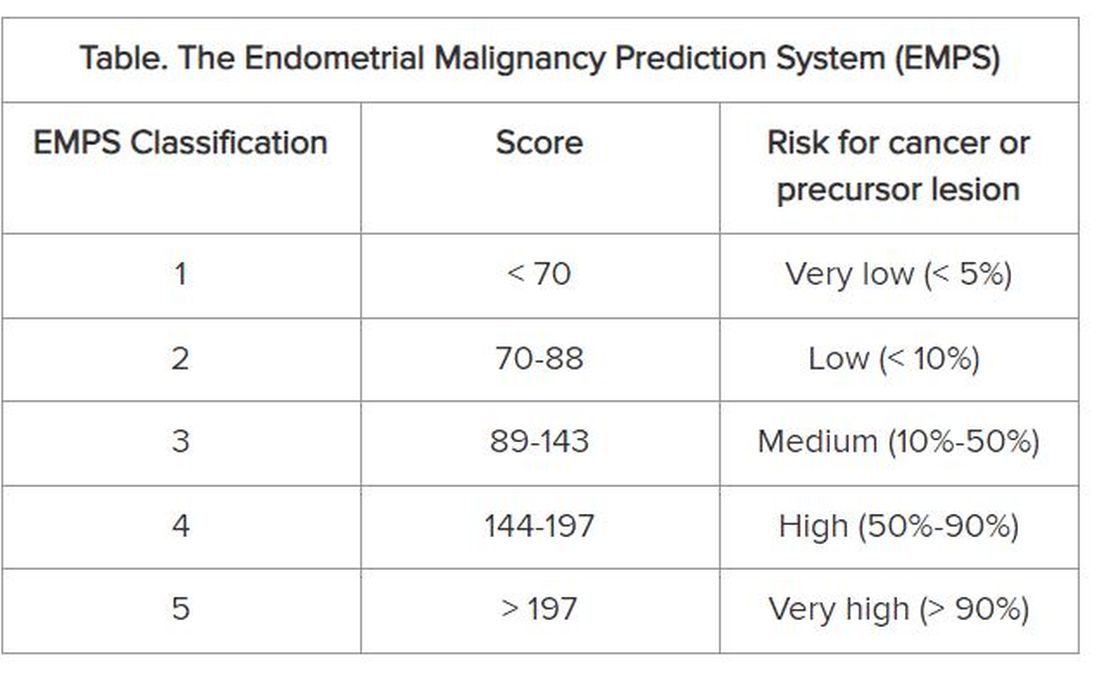

On the basis of these data, the group developed the EMPS nomogram. Physicians can use it to classify the patient’s risk according to the sum of the scores assigned to each of these factors.

The Table shows the classification system. The scoring tables available in the supplemental materials of the article can be accessed here.

Focus on Primary Care

The goal is not to remove patients classified as low risk from the hysteroscopy waiting list, but rather to prioritize those classified as high risk to get the examination, according to Dr. Bottura.

At the Municipal Hospital of Vila Santa Catarina, the average wait time for hysteroscopy was 120 days. But because the unit is focused on oncologic patients and has a high level of organization, this time is much shorter than observed in other parts of Brazil’s National Health Service, said Dr. Bottura. “Many patients are on the hysteroscopy waiting list for 2 years. Considering patients in more advanced stages [of endometrial cancer], it makes a difference,” she said.

Although the nomogram was developed in tertiary care, it is aimed at professionals working in primary care. The reason is that physicians from primary care health units refer women with clinical indications for hysteroscopy to specialized national health services, such as the Municipal Hospital of Vila Santa Catarina. “Our goal is the primary sector, to enable the clinic to refer this high-risk patient sooner. By the time you reach the tertiary sector, where hysteroscopies are performed, all patients will undergo the procedure. Usually, it is not the hospitals that predetermine the line, but rather the health clinics,” she explained.

The researchers hope to continue the research, starting with a prospective study. “We intend to apply and evaluate the tool within our own service to observe whether any patient with a high [EMPS] score patient ended up waiting too long to be referred. In fact, this will be a system validation step,” said Dr. Bottura.

In parallel, the team has a proposal to take the tool to health clinics in the same region as the study hospital. “We know this involves changing the protocol at a national level, so it’s more challenging,” said Dr. Bottura. She added that the final goal is to create a calculator, possibly an app, that allows primary care doctors to calculate the risk score in the office. This calculator could enable risk classification to be linked to patient referrals.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.