A 39-year-old black woman, gravida 1, para 0, with an intrauterine pregnancy of 34 weeks and three days (according to last menstrual period and nine-week ultrasound) presented to her Ob-Gyn office for a routine prenatal visit. She was found to have an elevated blood pressure with new onset of 2+ proteinuria. The patient was sent to the labor and delivery unit at the adjoining hospital for serial blood pressure readings, laboratory work, and fetal monitoring.

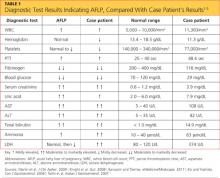

The patient’s previous medical history was limited to sinusitis. She was taking no prescription medications, and her only listed allergy was to pineapple. Initial lab studies revealed elevations in liver enzymes, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), uric acid, and serum creatinine, as well as thrombocytopenia (see Table 11-5). She also had a critically low blood glucose level, which conflicted with a normal follow-up reading.

At this point, the patient was thought to have HELLP syndrome6 (ie, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count), or possibly acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP).2,4,7-11 Additional labs were drawn immediately to confirm or rule out AFLP. These included repeat serum glucose (following a second reading with normal results), a serum ammonia level, prothrombin time (PT), and partial thromboplastin time (PTT). The most reliable values to distinguish AFLP from HELLP are profound hypoglycemia (found in 94% of women with AFLP12) and an elevated serum ammonia level.4

Given the serious nature of either diagnosis, immediate delivery of the infant was deemed necessary. Because the patient’s cervix was not found favorable for induction, she underwent low-transverse cesarean delivery without complications. She was noted to have essentially normal anatomy with the exception of a small subserosal fibroid posteriorly. Meconium-stained amniotic fluid was present. A male infant was delivered, weighing 5 lb with 1-minute and 5-minute Apgar scores of 8 and 9, respectively.

Postoperatively, the patient remained in the recovery area, where she received intensive monitoring. She experienced fluctuations in blood glucose, ranging from 33 to 144 mg/dL; she was started on 5% dextrose in lactated Ringer’s solution and treated with IV dextrose 50 g. While the patient was in surgical recovery, results from the second set of labs, drawn before surgery, were returned; findings included an elevated ammonia level and an abnormal coagulation panel, including PT of 25.3 sec, PTT of 48.4 sec, and a fibrinogen level of 116 mg/dL, confirming the suspected diagnosis of AFLP.

Magnesium sulfate, which had been started immediately postop, was discontinued on confirmation of the diagnosis of AFLP. The patient was initially somnolent as a result of general anesthesia but gradually returned to a fully normal sensorium by early morning on postop day 1. Postoperatively, the patient’s hemoglobin was found to be low (8.6 g/dL; reference range, 13.5 to 18.5 g/dL), so she was transfused with two units of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) and given fresh frozen plasma (FFP) to correct this coagulopathy. The patient’s platelets were also low at 82,000/mm3 (reference range, 140,000 to 340,000/mm3).

On postop day 1, the patient’s serum creatinine rose to 4.2 mg/dL and her total bilirubin increased to 14.4 mg/dL (reference ranges, 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL and < 1.0 mg/dL, respectively). Given the multiple systems affected by AFLP and the need for intensive supportive care, the patient was transferred to the ICU.

On her arrival at the ICU, the patient’s vital signs were initially stable, and she was alert and oriented. However, within the next few hours, she became hypotensive and encephalopathic. She required aggressive fluid resuscitation and multiple transfusions of PRBCs and FFP due to persistent anemia and coagulopathy. Her vital signs were stabilized, but she continued to need blood transfusions.

Postop day 2, the patient became less responsive and was soon unable to follow commands or speak clearly. Her breathing remained stable with just 3 L of oxygen by nasal cannula, but in order to prevent aspiration and in consideration of a postoperative ileus, it was necessary to place a nasogastric tube with low intermittent suction. This produced a bloody return, but no intervention other than close monitoring and transfusion was performed at that time.

Abdominal ultrasound showed ascites and mild left-sided hydronephrosis with no gallstones. The common bile duct measured 3 mm in diameter.

Although liver biopsy is considered the gold standard for a confirmed diagnosis of AFLP,13,14 this procedure was contraindicated by the patient’s coagulopathy. Concern was also expressed by one consultant that the patient might have thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) in addition to AFLP. TTP can manifest with similar findings, such as anemia, thrombocytopenia, neurologic symptoms, and renal abnormalities, but usually fever is involved, and the patient was afebrile. A catheter was placed for hemodialysis and therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE). Given that TTP-associated mortality is significantly decreased by use of TPE,15 this intervention was deemed prudent. The patient underwent TPE on three consecutive days, postop days 2 through 4.