Psychiatrists are markedly less likely than are office-based physicians in other specialties to accept insurance, according to a report published online Dec. 11 in JAMA Psychiatry.

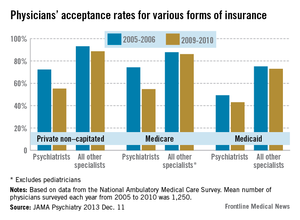

Moreover, psychiatrists’ rates of insurance acceptance are plummeting over time, compared with those of other physicians. In 2009-2010, almost half of all psychiatrists in the United States did not accept private non–capitated insurance, and more than half did not accept Medicare or Medicaid, said Dr. Tara F. Bishop of the departments of public health and medicine, Cornell University, New York, and her associates.

This can adversely affect access to mental health services for patients who are unable to pay for psychiatric care out of their own pockets.

"To our knowledge, no prior studies have documented such a striking difference in insurance acceptance rates between psychiatrists and physicians in other specialties. These low rates of acceptance may affect recent calls for increased access to mental health services, and if the trend of declining acceptance rates continues then the impact may be even more significant," the investigators noted.

Recent reports suggested that nonacceptance of insurance might be particularly high among psychiatrists. Dr. Bishop and her colleagues examined the issue using data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), a physician survey administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics.

The NAMCS includes data on a nationally representative sample of office-based physicians who account for 90% of outpatient visits across the country each year. The researchers restricted their analysis to study participants who reported that they accepted new patients and whether they accepted those patients’ insurance coverage, for each year between 2005 and 2010. The mean number of physicians surveyed each of these years was 1,250, and approximately 5.5% of them were psychiatrists.

The other specialties covered by NAMCS include internal medicine, general/family practice, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, cardiology, oncology, general surgery, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, neurology, urology, dermatology, otolaryngology, and others.

The percentage of psychiatrists who accepted private non–capitated insurance was lower than for all other specialties every year assessed, and it declined by 17% during the study period, from 72.3% in 2005-2006 to 55.3% in 2009-2010. In contrast, the percentage of physicians in other specialties who accepted private non–capitated insurance was 93.1% in 2005-2006 and declined only 4.4%, to 88.7%, in 2009-2010, the researchers said (JAMA Psychiatry 2013 Dec. 11 [doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862]).

Similarly, the percentage of psychiatrists who accepted Medicare was lower than that for all other specialists in every year assessed, and it decreased by nearly 20%, from 74.3% at the beginning of the study period to 54.8% at the end. In contrast, the percentage of physicians in other specialties who accepted Medicare did not change over time.

Psychiatrists’ Medicaid acceptance rates also were lower than those of all other specialties each year, but did not decline significantly over time. In 2009-2010, only 49.3% of psychiatrists accepted Medicaid, compared with 75.1% of physicians in other specialties.

This study was unable to assess why psychiatrists are so unlikely to accept insurance, but Dr. Bishop and her associates offered several potential reasons.

First, the time it takes to provide counseling and therapy might be uniquely long for psychiatrists, compared with other physicians. If psychiatrists cannot see as many patients in a day as other physicians, they might opt out of accepting insurance.

Second, psychiatrists might have such a demand for their services that they don’t need to accept insurance. This might stem in part from a shortage of psychiatrists: The number of graduates from psychiatry training programs has declined, while the current workforce is aging rapidly.

Third, the data indicated that solo practitioners were more likely than those in group practice to decline to accept insurance, and psychiatrists are more likely to be in solo practice than physicians in other specialties. "Solo practices often can function with much less infrastructure than larger single-specialty or multispecialty group practices. As a result, they may have little incentive to hire staff to interact with insurance companies," the investigators said.

Dr. Bishop and her colleagues cited several limitations. For example, physicians are not asked by the NAMCS why they opt not to accept insurance. Also, information about insurance acceptance on the part of physicians who practice in hospital outpatient departments is not collected by the NAMCS.

Still, the researchers’ findings suggest that policies aimed at improving access to timely psychiatric care might be limited by the fact that so many psychiatrists don’t accept insurance.