Clinical Review

5 ways to reduce infection risk during pregnancy

Which infections affect women more adversely during pregnancy, and how can risk of exposure to these infections be diminished?

Anushka Chelliah, MD, and Patrick Duff, MD

Dr. Duff is Associate Dean for Student Affairs and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology in the Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Florida College of Medicine.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The Zika virus has been strongly associated with congenital microcephaly and fetal loss among women infected during pregnancy.12 Following the recent large outbreak in Brazil, an alarmingly high number of Brazilian newborns with microcephaly have been observed. The total now exceeds 4,000. Because of these ominous findings, fetuses and neonates born to women with a history of infection should be evaluated for adverse effects of congenital infection.

Management strategies for Zika virus exposure during pregnancy

The incidence of Zika virus infection during pregnancy remains unknown. However, a pregnant woman may be infected in any trimester, and maternal-fetal transmission of the virus can occur throughout pregnancy. If a patient is pregnant and has travelled to areas of Zika virus transmission, or has had unprotected sexual contact with a partner who has had exposure, she should be carefully screened with a detailed review of systems and ultrasonography to evaluate for fetal microcephaly or intracranial calcifications. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initially recommended that, if a patient exhibited 2 or more symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection within 2 weeks of exposure or if sonographic evidence revealed fetal microcephaly or intracranial calcifications, she should be tested for Zika virus infection.11

More recently, the CDC issued new guidelines recommending that even asymptomatic women with exposure have serologic testing for infection and that all exposed women undergo serial ultrasound assessments.13 The CDC also recommends offering retesting in the mid second trimester for women who were exposed very early in gestation.

The best diagnostic test for infection is reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and, ideally, it should be completed within 4 days of symptom onset. Beyond 4 days after symptom onset, testing for Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM)-specific antibody and neutralizing antibody should be performed in addition to the RT-PCR test. At times, interpretation of antibody testing can be problematic because cross-reaction with related arboviruses is common. Moreover, Zika viremia decreases rapidly over time; therefore, if serum is collected even 5 to 7 days after symptom onset, a negative test does not definitively exclude infection (TABLE 1).

In the United States, local health departments should be contacted to facilitate testing, as the tests described above are not currently commercially available. If the local health department is unable to perform this testing, clinicians should contact the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (telephone: 1-970-221-6400) or visit their website (http://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/specimensub/arboviral-shipping.html) for detailed instructions on specimen submission.

Testing is not indicated for women without a history of travel to areas where Zika virus infection is endemic or without a history of unprotected sexual contact with someone who has been exposed to the infection.

Following the delivery of a live infant to an infected or exposed mother, detailed histopathologic evaluation of the placenta and umbilical cord should be performed. Frozen sections of placental and cord tissue should be tested for Zika virus RNA, and cord serum should be tested for Zika and dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies. In cases of fetal loss in the setting of relevant travel history or exposure (particularly maternal symptoms or sonographic evidence of microcephaly), RT-PCR testing and immunohistochemistry should be completed on fetal tissues, umbilical cord, and placenta.2

Treatment is supportive

At present, there is no vaccine for the Zika virus, and no hyperimmune globulin or anti‑ viral chemotherapy is available. Treatment is therefore supportive. Patients should be encouraged to rest and maintain hydration. The preferred antipyretic and analgesic is acetaminophen (650 mg orally every 6 hours or 1,000 mg orally every 8 hours). Aspirin should be avoided until dengue infection has been ruled out because of the related risk of bleeding with hemorrhagic fever. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided in the second half of pregnancy because of their effect on fetal renal blood flow (oligohydramnios) and stricture of the ductus arteriosus.

CASE 1 Continued

Given this patient’s recent travel, exposure to mosquito-borne illness, and clinical manifestations of malaise, rash, and joint pain, you proceed with serologic testing. The RT-PCR test is positive for Zika virus.

What should be the next step in the management of this patient?

Prenatal diagnosis and fetal surveillance

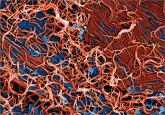

The recent epidemic of microcephaly and poor pregnancy outcomes reported in Brazil has been alarming and demonstrates an almost 20-fold increase in incidence of this condition between 2014–2015.14 Careful surveillance is needed for this birth defect and other poor pregnancy outcomes in association with the Zika virus. To date, a direct causal relationship between Zika virus infection and microcephaly has not been unequivocally established15; however; these microcephaly cases have yet to be attributed to any other cause (FIGURE 2)

Which infections affect women more adversely during pregnancy, and how can risk of exposure to these infections be diminished?

Nearly 100% of pregnant women infected with Ebola die. Clinicians should be aware of this statistic and familiar with general, as well as...

Treating acute cystitis effectively the first time, and more clinical guidance on preventing, identifying, and managing infection