Upper- and lower-extremity injuries can occur during gynecologic surgery. The incidence of lower-extremity injury is 1.1%-1.9% and upper-extremity injuries can occur in 0.16% of cases.1-5 Fortunately, most of the injuries are transient, sensory injuries that resolve spontaneously. However, a small percentage of injuries result in long-term sequelae.

The pathophysiology of the nerve injuries can be mechanistically separated into three categories: neuropraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. Neuropraxia results from nerve demyelination at the site of injury because of compression and typically resolves within weeks to months as the nerve is remyelinated. Axonotmesis results from severe compression with axon damage. This may take up to a year to resolve as axonal regeneration proceeds at the rate of 1 mm per day. This can be separated into second and third degree and refers to the severity of damage and the resultant persistent deficit. Neurotmesis results from complete transection and is associated with a poor prognosis without reparative surgery.

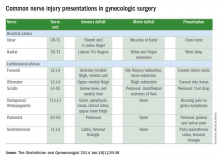

Brachial plexus

Stretch injury is the most common reason for a brachial plexus injury. This can occur if the arm board is extended to greater than 90 degrees from the patient’s torso or if the patient’s arm falls off of the arm board. Careful positioning and securing the patient’s arm on the arm board before draping can avoid this injury. A brachial plexus injury can also occur if shoulder braces are placed too laterally during minimally invasive surgery. Radial nerve injuries can occur if there is too much pressure on the humerus during positioning. Ulnar injuries arise from pressure placed on the medial aspect of the elbow.

Tip #1: When tucking a patient’s arm for minimally invasive surgery, appropriate padding should be placed around the elbow and wrist, and the arm should be in the “thumbs-up” position.

Tip #2: Shoulder blocks should be placed over the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

Lumbosacral plexus

The femoral nerve is the nerve most commonly injured during gynecologic surgery and this usually occurs because of compression of the nerve from the lateral blades of self-retaining retractors. One study showed an 8% incidence of injury from self-retaining retractors, compared with less than 1% when the retractors were not used.6 The femoral nerve can also be stretched when patients are placed in the lithotomy position and the hip is hyperflexed.

As with brachial injury prevention, patients should be positioned prior to draping and care must be taken to not hyperflex or externally rotate the hip during minimally invasive surgical procedures. With the introduction of robot-assisted surgery, care must be taken when docking the robot and surgeons must resist excessive movement of the stirrups.

Tip #3: During laparotomy, surgeons should use the shortest blades that allow for adequate visualization and check the blades during the procedure to ensure that excessive pressure is not placed on the psoas muscle. Consider intermittently releasing the pressure on the lateral blades during other portions of the procedure.

Tip #4: Make sure the stirrups are at the same height and that the leg is in line with the patient’s contralateral shoulder.

Obturator nerve injuries can occur during retroperitoneal dissection for pelvic lymphadenectomy (obturator nodes) and can be either a transection or a cautery injury. It can also be injured during urogynecologic procedures including paravaginal defect repairs and during the placement of transobturator tapes.

The sciatic nerve and its branch, the common peroneal, are generally injured because of excessive stretch or pressure. Both nerves can be injured from hyperflexion of the thigh and the common peroneal can suffer a pressure injury as it courses around the lateral head of the fibula. Therefore, care during lithotomy positioning with both candy cane and Allen stirrups is critical during vaginal surgery.

Tip #5: Ensure that the lateral fibula is not touching the stirrup or that padding is placed between the fibular head and the stirrup.

The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves are typically injured via suture entrapment from low transverse skin incisions, though laparoscopic injury has also been reported. The incidence after a Pfannenstiel incision is about 3.7%.7

Tip #6: Avoid extending the low transverse incision beyond the lateral margin of the rectus muscle, and do not extend the fascial closure suture more than 1.5 cm from the lateral edge of the fascial incision to avoid catching the nerve with the suture.

The pudendal nerve is most commonly injured during vaginal procedures such as sacrospinous fixation. Pain is typically worse when seated.

The genitofemoral nerve is typically injured during retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, particularly the external iliac nodes. The nerve is small and runs lateral to the external iliac artery. It can suffer cautery and transection injuries. Usually, the paresthesias over the mons pubis, labia majora, and medial inner thigh are temporary.

Tip #7: Care should be taken to identify and spare the nerve during retroperitoneal dissection or external iliac node removal.

Nerve injuries during gynecologic surgery are common and are a significant cause of potential morbidity. While occasionally unavoidable and inherent to the surgical procedure, many times the injury could be prevented with proper attention and care to patient positioning and retractor use. Gynecologists should be aware of the risks and have a through understanding of the anatomy. However, should an injury occur, the patient can be reassured that most are self-limited and full recovery is generally expected. In a prospective study, the median time to resolution of symptoms was 31.5 days (range, 1 day to 6 months).5

References

1. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2014;16:29-36.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 1988 Nov;31(3):462-6.

3. Fertil Steril. 1993 Oct;60(4):729-32.

4. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007 Sep-Oct;14(5):664-72.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Nov;201(5):531.e1-7.

6. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1985 Dec;20(6):385-92.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Apr;111(4):839-46.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email her at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.