Calcium and calcium supplements: The data continue to grow

Anderson JJ, Kruszka B, Delaney JA, et al. Calcium intake from diet and supplements and the risk of coronary artery calcification and its progression among older adults: 10-year follow-up of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) [published online ahead of print October 11, 2016]. J Am Heart Assoc. pii: e003815.

Billington EO, Bristow SM, Gamble GD, et al. Acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure: randomised, crossover trial in postmenopausal women [published online ahead of print August 20, 2016]. Osteoporos Int. doi:10.1007/s00198-016-3744-y.

Crandall CJ, Aragaki AK, LeBoff MS, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and height loss: findings from the Women's Health Initiative Calcium and Vitamin D clinical trial [published online ahead of print August 1, 2016]. Menopause. doi:10.1097 /GME.0000000000000704.

In 2001, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Panel on osteoporosis concluded that calcium intake is crucial to maintain bone mass and should be maintained at 1,000-1,500 mg/day in older adults. The panel acknowledged that the majority of older adults did not meet the recommended intake from dietary sources alone, and therefore would require calcium supplementation. Calcium supplements are one of the most commonly used dietary supplements, and population-based surveys have shown that they are used by the majority of older men and women in the United States.7

More recently results from large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of calcium supplements have been reported, leading to concerns about calcium efficacy for fracture risk and safety. Bolland and colleagues8 reported that calcium supplements increased the rate of cardiovascular events in healthy older women and suggested that their role in osteoporosis management be reconsidered. More recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended against calcium supplements for the primary prevention of fractures in noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women.9

The association between calcium intake and CVD events

Anderson and colleagues acknowledged that recent randomized data suggest that calcium supplements may be associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events. Using a longitudinal cohort study, they assessed the association between calcium intake, from both foods and supplements, and atherosclerosis, as measured by coronary artery calcification (CAC).

Details of the study by Anderson and colleagues

The authors studied 5,448 adults free of clinically diagnosed CVD (52% female; age range, 45-84 years) from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Baseline total calcium intake was assessed from diet (using a food frequency questionnaire) and calcium supplements (by a medication inventory) and categorized into quintiles based on overall population distribution. Baseline CAC was measured by computed tomography (CT) scan, and CAC measurements were repeated in 2,742 participants approximately 10 years later. Women had higher calcium intakes than men.

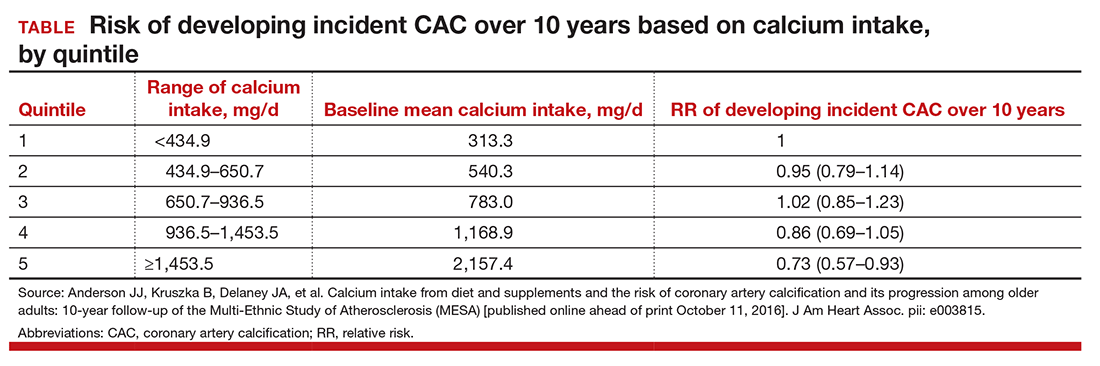

After adjustment for potential confounders, among 1,567 participants without baseline CAC, the relative risk (RR) of developing incident CAC over 10 years, by quintile 1 to 5 of calcium intake is included in the TABLE. After accounting for total calcium intake, calcium supplement use was associated with increased risk for incident CAC (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.07-1.39). No relation was found between baseline calcium intake and 10-year changes in CAC among those participants with baseline CAC less than zero.

They concluded that high total calcium intake was associated with a decreased risk of incident atherosclerosis over long-term follow-up, particularly if achieved without supplement use. However, calcium supplement use may increase the risk for incident CAC.

Related article:

Does the discontinuation of menopausal hormone therapy affect a woman’s cardiovascular risk?

Calcium supplements and blood pressure

Billington and colleagues acknowledged that calcium supplements appear to increase cardiovascular risk but that the mechanism is unknown. They had previously reported that blood pressure declines over the course of the day in older women.10

Details of the study by Billington and colleagues

In this new study the investigators examined the acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure in a randomized controlled crossover trial in 40 healthy postmenopausal women (mean age, 71 years; body mass index [BMI], 27.2 kg/m2). Women attended on 2 occasions, with visits separated by 7 or more days. At each visit, they received either 1 g of calcium as citrate or placebo. Blood pressure and serum calcium concentrations were measured immediately before and 2, 4, and 6 hours after each intervention.

Ionized and total calcium concentrations increased after calcium (P<.0001 vs placebo). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements decreased after both calcium and placebo but significantly less so after calcium (P=.02). The reduction in SBP from baseline was smaller after calcium compared with placebo by 6 mm Hg at 4 hours (P=.036) and by 9 mm Hg at 6 hours (P=.002). The reduction in diastolic blood pressure was similar after calcium and placebo.

These findings indicate that the use of calcium supplements in postmenopausal women attenuates the postbreakfast reduction in SBP by 6 to 9 mm Hg. Whether these changes in blood pressure influence cardiovascular risk requires further study.

Association between calcium, vitamin D, and height loss

Crandall and colleagues looked at the association between calcium and vitamin D supplementation and height loss in 36,282 participants of the Women's Health Initiative Calcium and Vitamin D trial.

Details of the study by Crandall and colleagues

The authors performed a post hoc analysis of data from a double-blind randomized controlled trial of 1,000 mg of elemental calcium as calcium carbonate with 400 IU of vitamin D3 daily (CaD) or placebo in postmenopausal women at 40 US clinical centers. Height was measured annually (mean follow-up, 5.9 years) with a stadiometer.

Average height loss was 1.28 mm/yr among participants assigned to CaD, versus 1.26 mm/yr for women assigned to placebo (P=.35). A strong association (P<.001) was observed between age group and height loss. The study authors concluded that, compared with placebo, calcium and vitamin D supplementation used in this trial did not prevent height loss in healthy postmenopausal women.

Adequate calcium is necessary for bone health. While calcium supplementation may not be adequate to prevent fractures, it is also not involved in the inevitable loss of overall height seen in postmenopausal women. Calcium supplementation has been implicated in an increase in CVD. These data seem to indicate that, while calcium supplementation results in higher systolic blood pressure during the day, as well as higher coronary artery calcium scores, greater dietary calcium actually may decrease the incidence of atherosclerosis.