LAS VEGAS – Severe obstetric perineal trauma can often be avoided, even in operative deliveries, with the use of a suite of evidence-based interventions, according to findings from two prospective studies.

Collectively, these interventions resulted in significant reductions in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations in both military and civilian settings, according to research presented at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

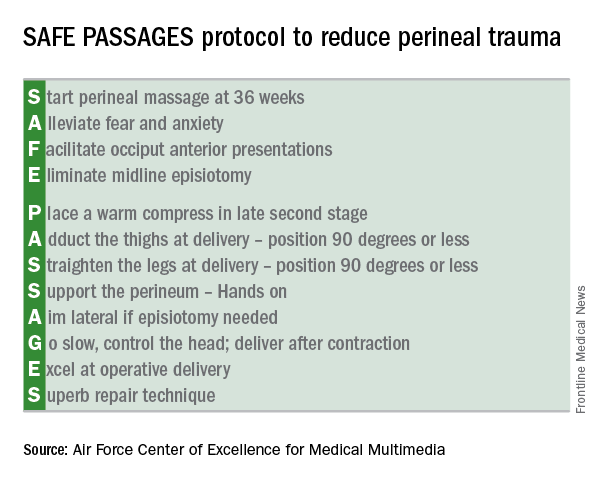

The sequence of interventions, known by the mnemonic SAFE PASSAGES, significantly reduced the incidence of obstetric trauma related to both instrumental and noninstrumental vaginal deliveries within military hospitals, and was also effective in a separate study conducted in four civilian hospitals.Developed by the Military Health System, the SAFE PASSAGES protocol brings together interventions that help achieve a controlled delivery over a relaxed perineum, minimizing risk for maternal obstetric trauma.

The entire SAFE PASSAGES curriculum is available free online.

Military results

In a prospective cohort design, 272,161 deliveries conducted before the 2011 implementation of the SAFE PASSAGES training program were compared with 451,446 postimplementation deliveries. Primary outcome measures were the incidence of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations during vaginal deliveries with and without instrumentation.

For vaginal deliveries with instrumentation within one service branch of the military medical system (Service X), implementation of SAFE PASSAGES training was associated with a 63.6% reduction in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations, compared with preintervention rates (P less than .001).

The other two services – Service Y and Service Z – received just administrative encouragement and saw a 15.5% reduction and a 12.6% increase in significant obstetric trauma when instrumentation-assisted vaginal deliveries were performed (P = .04 and .30, respectively), according to Merlin Fausett, MD, an ob.gyn. currently in private practice in Missoula, Mont., who led the SAFE PASSAGES efforts before retiring from the Air Force.

For vaginal deliveries performed without instrumentation, the rates also fell for Service X, which saw a 41.8% reduction in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations (P less than .002). The other services saw a 16% increase and a 12% decrease with administrative encouragement alone (P = .48 and .08, respectively).

Though the military training program had initially been conducted in person, Dr. Fausett said that the program was switched to web-based simulations because of budget constraints. Efficacy remained high, he said.

Civilian results

When the team-based simulation that formed the core of the military SAFE PASSAGES training was rolled out in a large civilian health care system, similar improvements were seen.

Over an 18-month period, 675 nurses, midwives, and physicians received simulation-based training in the SAFE PASSAGES techniques. Overall, severe perineal laceration rates in the civilian facilities were down by 38.53% after adoption of SAFE PASSAGES.

“We have really achieved a culture shift,” said Emily Marko, MD, an ob.gyn. and clerkship director for the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine Inova Campus in Falls Church, Va. “This really requires the whole delivery team to get involved: the patient, the patient’s support person, the nurses, any midwives or doulas that are there,” she said. “To tell you the truth, this whole program is about paying attention to the perineum, and not rushing delivery.”

Posttraining surveys showed that 95% of providers had changed their practice patterns after training in the delivery strategies.

Interventions

The emphasis in SAFE PASSAGES is to achieve a slow, controlled delivery and to minimize strain on the perineum by means of conditioning, relaxation, and positioning.

The first intervention is to have pregnant women “start” perineal massage at 36 weeks. Next, providers are urged to “alleviate” maternal fears. Providers are also encouraged to recognize posterior presentations, and to “facilitate” an anterior presentation through rotation. The “E” in SAFE stands for “eliminating” midline episiotomies – one of the more difficult practices to shift, according to both Dr. Fausett and Dr. Marko.

Despite a wealth of evidence showing fewer anal sphincter disruptions and better overall outcomes, it’s been difficult to convince U.S. physicians to adopt the mediolateral episiotomy technique that’s widely adopted in Europe, they said.

The protocol calls for “placing” a warm compress over the perineum during labor to encourage relaxation and stretching. Though prenatal perineal massage is encouraged, Dr. Marko said that intrapartum massage is not, as it’s thought to contribute to edema when performed during labor.

During delivery, leg positioning to reduce stretching of the perineum is also important: The thighs should be “adducted” to 90 degrees or less, and “straightened” to 90 degrees or less as well. Though this can make “a bit of a tight space” for the delivering physician, Dr. Marko said, it really “helps engage the pelvic muscles to support the perineum,” and a few technique adjustments make the position workable.

The perineum should be “supported” during delivery by one hand of the delivering practitioner forming a U shape with the thumb and forefinger, with the first webspace overlying the posterior fourchette. Reinforcing the importance of avoiding a midline episiotomy, the “A” of passages stands for “aiming” lateral when an episiotomy is needed.

During the delivery, the physician should “go” slow, controlling the head and delivering after, rather than during, a contraction.

It’s important to be comfortable with forceps deliveries and vacuum extractions in order to minimize both maternal and fetal trauma; thus, physicians should “excel” at operative delivery, according to the protocol.

The SAFE PASSAGES website includes comprehensive explanations, with graphics and demonstrations using a model, of both forceps and vacuum delivery techniques.

Finally, should a laceration occur, the SAFE PASSAGES website provides detailed explanations of repair techniques, with an emphasis on understanding perineal, vaginal, and anal anatomy so “superb” approximation and repair can be achieved.

Though obstetric trauma may not be life threatening, it’s still associated with significant and persistent morbidity. When perineal and pelvic floor trauma disrupts the anal sphincter, anal incontinence can occur, even after a meticulous attempt at repair. Perineal and pelvic floor trauma can result in a host of urinary and sexual problems as well.

After the intensive training period, Dr. Fausett said, “laceration rates can creep back up if people forget about it and stop paying attention to it. But where it becomes a culture, the rates can stay low. Standardized training can reduce perineal trauma rates without increasing cesarean or neonatal trauma rates,” Dr. Fausett said.

Dr. Marko and Dr. Fausett reported having no conflicts of interest.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes