CASE Managing pain associated with prolapse and SUI surgery

A 46-year-old woman (G4P4) described 3 years of worsening symptoms related to recurrent stage-3 palpable uterine prolapse. She had associated symptomatic stress urinary incontinence. She had been treated for uterine prolapse 5 years ago with vaginal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy, and high uterosacral-ligament suspension.

After consultation, the patient elected to undergo laparoscopic sacral colpopexy, a mid-urethral sling, and possible anterior and posterior colporrhaphy. Appropriate discussion about the risks and benefits of mesh was provided preoperatively. The surgical team judged her to be highly motivated; she wanted same-day outpatient surgery so that she could go home and then return to work. She had excellent support at home.

How would you counsel this patient about expected postoperative pain? Which medications would you administer to her preoperatively and perioperatively? Which ones would you prescribe for her to manage pain postoperatively?

Adverse impact of prescription opioids in the United States

Although fewer than 5% of the world’s population live in the United States, nearly 80% of the world’s opioids are written for them.1 In 2012, 259 million prescriptions were written for opioids in the United States—more than enough to give every American adult their own bottle of pills.2 Sadly, drug overdose is now a leading cause of accidental death in the United States, with 52,404 lethal drug overdoses in 2015. A startling statistic is that prescription opioid abuse is driving this epidemic, with 20,101 overdose deaths related to prescription pain relievers and 12,990 overdose deaths related to heroin in 2015.3

It is likely that there are multiple reasons prescribing of opioids is epidemic. Surgical pain is a common indication for opioid prescriptions; fewer than half of patients who undergo surgery report adequate postoperative pain relief.4 Recognition of these deficits in pain management has inspired national campaigns to improve patients’ experience with pain and aggressively address pain with drugs such as opioids.5

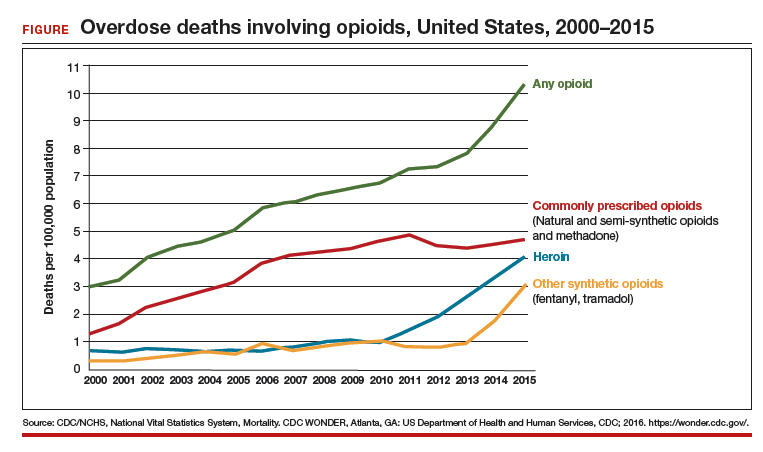

At the same time, marketing efforts by the pharmaceutical industry sought to reassure the medical community that patients would not become addicted to prescription opioid pain relievers if physical pain was the indication for such prescriptions. In response, health care providers began to prescribe opioids at a greater rate. As providers were encouraged to increase prescriptions, opioid medications began to be misused—and only then did it become clear that these medications are, in fact, highly addictive.6 Opioid abuse and overdose rates began to increase; in 2015, more than 33,000 Americans died because of an opioid overdose, including prescription opioids and heroin7 (FIGURE). In fact, although most people recognize the threat posed by illegal heroin, most of the 2 million who abused opioids in 2015 in the United States suffered from prescription abuse; only about a quarter, or about 600,000, abused heroin.8 In addition, more than 80% of people who abuse heroin initially abused prescription opioids.9

Read about medications and strategies for multimodal pain management.