Modest weight loss of 5% to 10% among patients who are overweight or obese can result in a clinically relevant reduction in cardiovascular (CV) disease risk.1 This amount of weight loss can increase insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue, liver, and muscle, and have a positive impact on blood sugar, blood pressure, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.1,2

All patients who are obese or overweight with increased CV risk should be counseled on diet, exercise, and other behavioral interventions.3 Weight loss secondary to lifestyle modification alone, however, leads to adaptive physiologic responses, which increase appetite and reduce energy expenditure.4–6

Pharmacotherapy can counteract this metabolic adaptation and lead to sustained weight loss. Antiobesity medication can be considered if a patient has a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2 or ≥27 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, or obstructive sleep apnea.3,7

For patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2 or BMI ≥27 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities:

- Consider antiobesity pharmacotherapy when diet, exercise, and behavior modification do not produce sufficient weight loss. A

- Continue an antiobesity medication if it is deemed effective and well tolerated.A

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

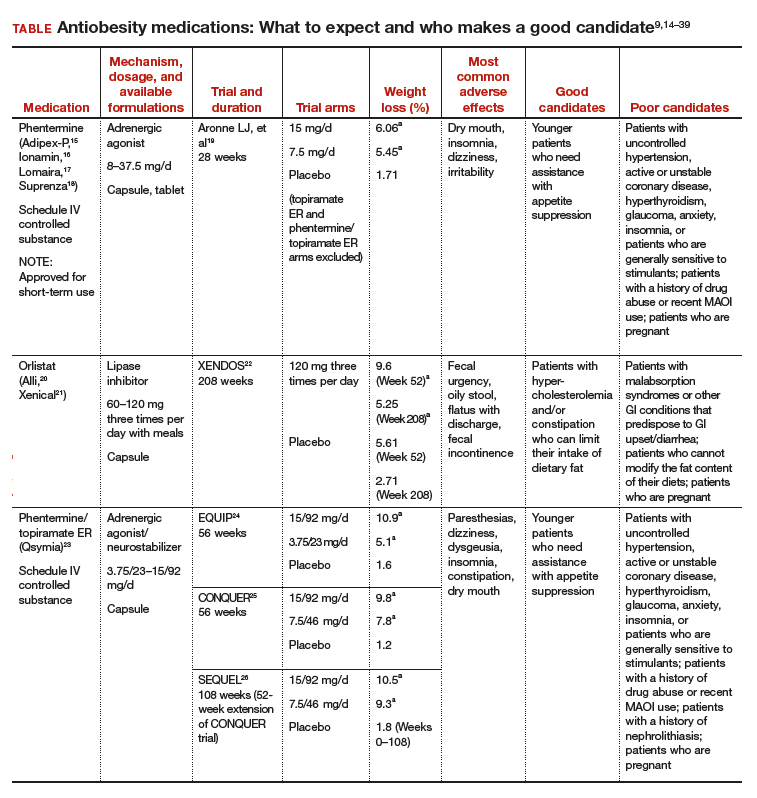

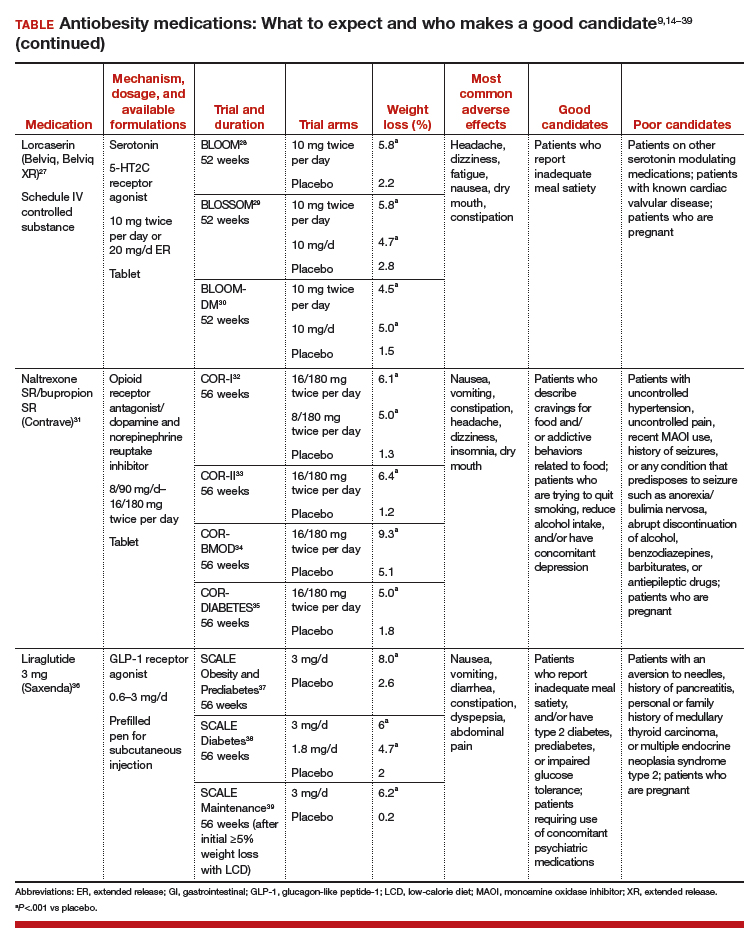

Until recently, there were few pharmacologic options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of obesity. The mainstays of treatment were phentermine (Adipex-P, Ionamin, Suprenza) and orlistat (Alli, Xenical). Since 2012, however, 4 agents have been approved as adjuncts to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity for long-term weight management.8,9 Phentermine/topiramate extended-release (ER) (Qsymia) and lorcaserin (Belviq) were approved in 2012,10,11 and naltrexone sustained release (SR)/bupropion SR (Contrave) and liraglutide 3 mg (Saxenda) were approved in 201412,13 (TABLE9,14–39). These medications have the potential to not only limit weight gain but also promote weight loss and, thus, improve blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, and insulin.40

Despite the growing obesity epidemic and the availability of several additional medications for chronic weight management, use of antiobesity pharmacotherapy has been limited. Barriers to use include inadequate training of health care professionals, poor insurance coverage for new agents, and low reimbursement for office visits to address weight.41

In addition, the number of obesity medicine specialists, while increasing, is still not sufficient. Therefore, it is imperative for other health care professionals—including ObGyns—to be aware of the treatment options available to patients who are overweight or obese and to be adept at using them.

In this review, we present 4 cases that depict patients who could benefit from the addition of antiobesity pharmacotherapy to a comprehen‑sive treatment plan that includes diet, physical activity, and behavioral modification.

CASE 1 Young obese woman is unable to lose weight

A 27-year-old woman with obesity (BMI 33 kg/m2),hyperlipidemia, and migraine headaches, pre‑sents for weight management. Despite a calorie-reduced diet and 200 minutes per week of exercise for the past 6 months, she has been unable to lose weight. The only medications she is taking are oral contraceptive pills and sumatriptan, as needed. She suffers from migraines 3 times a month and has no anxiety. Laboratory test results are normal with the exception of an elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level.

Which medication is an appropriate next step for this patient?