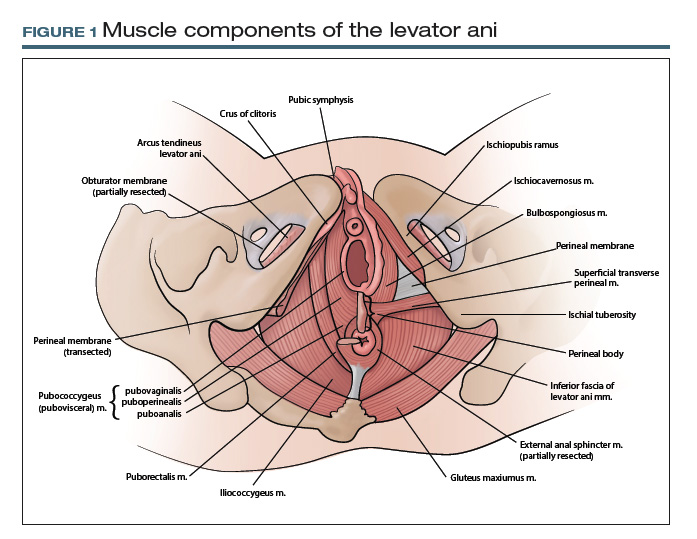

TA includes approved options in English and Latin and lists a unique identification number for each term (shown in parentheses in the examples that follow). For instance, to answer the question posed earlier, the levator ani (A04.5.04.002) is comprised of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), puborectalis (A04.5.04.007), and iliococcygeus (A04.5.04.008) muscles (FIGURE 1).The terms pubovisceral and pubovisceralis are used synonymously in the literature with pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003).3 The additional terms puboperinealis (A04.5.04.004), pubovaginalis (A04.5.04.005), and puboanalis (A04.5.04.006) are subcomponents of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), and this relationship is indicated in TA by indentation formatting.4 Finally, the ischiococcygeus (A04.5.04.011) muscle is not considered part of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).

Revisiting the mesh erosion case: Reporting your findings

After reviewing the recommended terminology for the anterior pelvis,3,4 you might draft a report as follows: “A mesh erosion was visualized in anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006) at the level of the mid-urethra extending into ‘anterior and lateral vaginal sulci’ (proposed term). In addition, there is a painful tight band in the ‘lateral vaginal wall’ (proposed term) near the ischial spine (A02.5.01.205). Palpation of this band reproduces the patient’s pain and causes secondary spasm of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).” Certainly, TA identification numbers would not be expected to be included in medical communication; they are included here for reference.

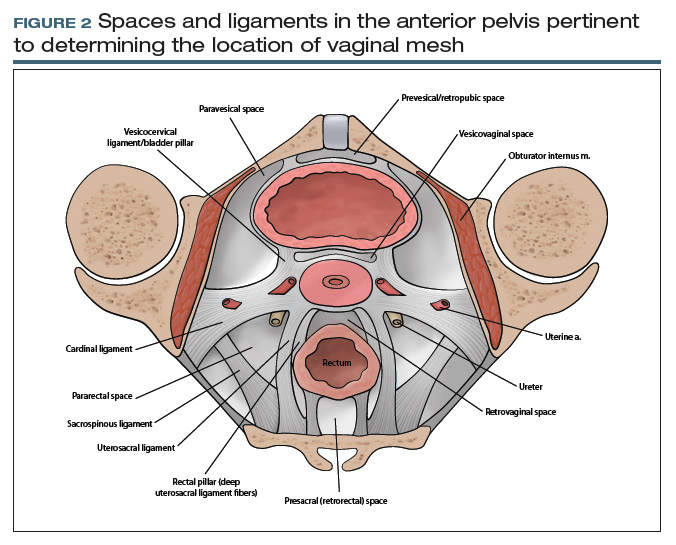

From your description, your urogynecology colleague has a better understanding of the location of your patient’s vaginal mesh and requests her operative report from an outside facility. In the operative report, the surgeon described “placement of mesh into the vagina, dissection through the rectal spaces, and anchoring of the mesh into the levator/pelvic muscles, the cervix, and lastly to the paraurethral ligaments,” and “passage of trocars through the cave of Retzius at the level of the midurethra” (FIGURE 2).

Based on this description, the urogynecologist ascertains that the mesh is located in the anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006), with passage of anchoring arms through the bilateral sacrospinous ligaments (A03.6.03.007) and retropubic space (A10.1.01.003). Exposed mesh is visible, extending from the midurethra to the “anterior and lateral vaginal sulci” (proposed term).

This case clearly demonstrates the importance of communication between providers for patient care, since understanding the patient’s anatomy and the location of the vaginal mesh is important for planning surgical excision of the exposed mesh.

Additional initiatives

Outlining standardized terminology is just the first step toward improving the anatomic “language” used among providers. Ongoing efforts from the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group include a special imaging group’s review of imaging modalities (ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomography) to improve standardization on reporting clinical anatomy. In addition, SGS has developed a group to create educational content related to the structures identified by the terminology group from cadaveric or surgical dissections. Educational materials will be compiled to help physicians and learners expand their anatomic understanding and improve their communication.

Further details of the Pelvic Anatomy Group’s efforts can be found on the SGS website at https://www.sgsonline.org.