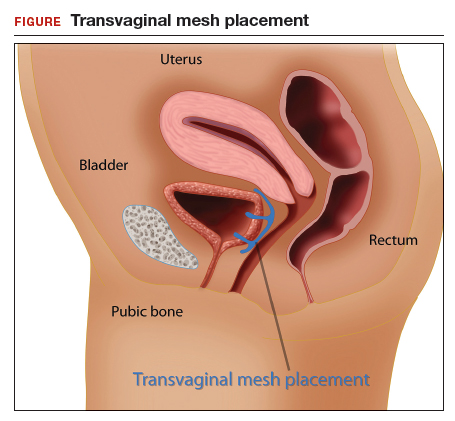

In the late 1990s the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) permitted use of the first transvaginal meshes, which were designed to treat SUI—the midurethral sling. These mesh slings were so successful that similar meshes were developed to treat POP.7 Almost immediately there were problems with the new POP devices, and 3 years later Boston Scientific recalled its device.8 Nonetheless, the FDA cleared more than 150 devices using surgical mesh for urogynecologic indications (FIGURE).9

Mesh complications

Managing complications from intravesical mesh is a clinically challenging problem. Bladder perforation, stone formation, and penetration through the vagina can occur. Bladder-related complications can manifest as recurrent UTIs and obstructive urinary symptoms, especially in association with stone formation. From the gynecologic perspective, the more common complications with mesh utilization are pelvic pain, groin pain, dyspareunia, contracture and scarring of mesh, and narrowing of the vaginal canal.10 Mesh erosion problems will occur in an estimated 10% to 25% of transvaginal mesh POP implants.11

In 2008, a comparison of transvaginal mesh to native tissue repair (suture-based) or other (biologic) grafts was published.12 The bottom line: there is insufficient evidence to suggest that transvaginal mesh significantly improves outcomes for both posterior and apical defects.

Legal background

Mesh used for surgical purposes is a medical device, which legally is a product—a special product to be sure, but a product nonetheless. Products are subject to product liability rules. Mesh is also subject to an FDA regulatory system. We will briefly discuss products liability and the regulation of devices, both of which have played important roles in mesh-related injuries.

Products liability

As a general matter, defective products subject their manufacturer and seller to liability. There are several legal theories regarding product liability: negligence (in which the defect was caused through carelessness), breach of warranty or guarantee (in addition to express warranties, there are a number of implied warranties for products, including that it is fit for its intended purpose), and strict liability (there was a defect in the product, but it may not have been because of negligence). The product may be defective in the way it was designed, manufactured, or packaged, or it may be defective because adequate instructions and warning were not given to consumers.

Of course, not every product involved in an injury is defective—most automobile accidents, for example, are not the result of any defect in the automobile. In medicine, almost no product (device or pharmaceutical) is entirely safe. In some ways they are unavoidably unsafe and bound to cause some injuries. But when injuries are caused by a defect in the product (design or manufacturing defect or failure to warn), then there may be products liability. Most products liability cases arise under state law.

FDA’s device regulations

Both drugs and medical devices are subject to FDA review and ordinarily require some form of FDA clearance before they may be marketed. In the case of devices, the FDA has 3 classes, with an increase in risk to the user from Class I to III. Various levels of FDA review are required before marketing of the device is permitted, again with the intensity of review increasing from I to III as follows:

- Class I devices pose the least risk, have the least regulation, and are subject to general controls (ie, manufacturing and marketing practices).

- Class II devices pose slightly higher risks and are subject to special controls in addition to the criteria for Class I.

- Class III devices pose the most risk to patients and require premarket approval (scientific review and studies are required to ensure efficacy and safety).13

Continue to: There are a number of limits on manufacturer liability for defective devices...