Medication to help prevent breast cancer is not recommended for women without increased risk, but could benefit women at increased risk for the disease, according to an update from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

In a statement published in JAMA, the USPSTF issued a D recommendation against routine medications to prevent breast cancer in women with no increased risk, but issued a B recommendation that medications should be considered in high-risk women.“Although evidence on the best interval at which to reassess risk and indications for risk-reducing medications is not available, a pragmatic approach would be to repeat risk assessment when there is a significant change in breast cancer risk factors; for instance, when a family member is diagnosed with breast cancer or when there is a new diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia or lobular carcinoma in situ on breast biopsy,” wrote Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and members of the task force.

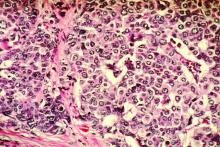

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic women aged 35 years and older, including women with a history of benign breast lesions, but does not apply to women with current or previous breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ. The recommendation remains essentially unchanged from the 2013 version, with the addition of aromatase inhibitors (AIs) in the list of options for risk-reducing medications.

In an evidence report accompanying the recommendation, researchers reviewed data from 46 studies including 82 articles and more than 5 million individuals. Overall, among 10 placebo-controlled trials, tamoxifen, raloxifene, and AIs were associated with lower incidence of invasive breast cancer, with risk ratios of 0.69, 0.44, and 0.45, respectively.

However, based on the risk of adverse effects including thromboembolic events, endometrial cancer, and cataracts, the task force determined that the benefits of these medications were no greater than small in women with no risk factors. In addition, 18 risk assessments in 25 studies showed low levels of accuracy in predicting breast cancer risk.

Data from the studies reviewed by the USPSTF showed that the harms of AIs included vasomotor symptoms, GI symptoms, musculoskeletal pain, and potential increased risk of cardiovascular events and fractures. Potential harms of other medications to help prevent breast cancer (tamoxifen and raloxifene) included increased risk for venous thromboembolic events, endometrial cancer, cataracts, and hot flashes.

The findings were limited by several factors including possible publication bias, variation in risk assessment studies, and inability to conduct subgroup analysis, wrote Heidi D. Nelson, MD, of Oregon Health & Sciences University, Portland, and colleagues in the evidence report.

“Although most results are consistent with the 2013 USPSTF review, this update provides additional evidence of the inaccuracy of risk assessment methods,” they noted.

“The USPSTF recommendations, and the accompanying systematic evidence review by Nelson and colleagues rightfully focus on the need to identify women for whom the benefits are likely to outweigh harms, but they also underscore persistent uncertainties about how to accomplish that goal,” wrote Lydia E. Pace, MD, and Nancy L. Keating, MD, both of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Sept 3;322:821-23).

“Identifying safer and more effective preventive medications would help mitigate the low discriminatory accuracy of existing breast cancer risk models,” the editorialists wrote. “Meanwhile, considering risk-reducing medications for women with 5-year risk greater than 3% seems reasonable, as well as for women with atypical hyperplasia and [lobular carcinoma in situ].”

The research was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Neither the task force researchers nor the editorialists reported relevant financial conflicts.

SOURCEs: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2019 Sept 3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11885; Nelson HD et al. JAMA. 2019 Sept 3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5780.