Surgical technique for uterus recipients

For the recipient surgery, entry is achieved via a midline, vertical laparotomy. The external iliac vessels are exposed, and the sites of vascular anastomoses are identified. The peritoneal reflection of the bladder is identified and dissected away to expose the anterior vagina, and the vagina is opened to a diameter that matches the donor, typically using a monopolar electrosurgical cutting instrument.

The vault of the donor vagina will be attached to the recipient’s existing vagina or vaginal pouch. It is important to identify recipient vaginal mucosa and incorporate it into the vaginal anastomosis to reduce the risk of vaginal stricture. We recommend that the vaginal mucosa be tagged with PDS II sutures or grasped with allis clamps to prevent retraction.

Surgical teams have taken multiple approaches to vaginal anastomosis. The Cleveland Clinic has used both a running suture as well as a horizontal mattress stitch for closure. For the latter, a 30-inch double-armed 2.0 Vicryl allows for complete suturing of the recipient vagina – with eight stitches placed circumferentially – before the uterus is placed. Both ends of the suture are passed intra-abdominal to intravaginal in the recipient.9

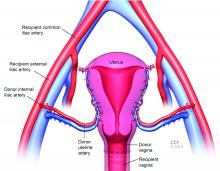

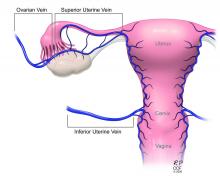

Once the donor uterus is suspended, attention focuses on vascular anastomosis, with bilateral end-to-side anastomosis between the donor anterior division of the internal iliac arteries and the external iliac vessels of the recipient, and with venous drainage commonly achieved through the uterine veins draining into the internal or external iliac vein of the recipient. As mentioned, recent cases involving living donors have also demonstrated success with the use of ovarian and/or utero-ovarian veins. Care should be taken to avoid having tension or twisting across the anastomosis.

After adequate graft perfusion is confirmed, with the uterus turning from a dusky color to a pink and well-perfused organ, the vaginal anastomosis is completed, with the arms of the double-armed suture passed through the donor vagina, from intravaginal to intra-abdominal. Tension should be evenly spread along the recipient and donor vagina in order to reduce the formation of granulation tissue and the severity of future vaginal stricturing.

For uterine fixation, polypropylene sutures are placed between the graft uterosacral ligaments and recipient uterine rudiments, and between the graft round ligaments and the recipient pelvic side wall at the level of the deep inguinal ring.

Current uterus transplantation protocols require removal of the uterus after one or two live births are achieved, so that recipients will not be exposed to long-term immunosuppression.

Complications and controversies

Postoperative vaginal strictures can make embryo transfer difficult and are a common complication in both living- and deceased-donor models. The Cleveland Clinic team has applied techniques from vaginal reconstructive surgery to try to reduce the occurrence of postoperative strictures – mainly increasing attention paid to anastomosis tissue–site preparation and closure of the anastomosis using a tension-free interrupted suture technique, as described above.9 The jury is out on whether such changes are sufficient, and a more complete understanding of the causes of vaginal stricture is needed.

Other perioperative complications include infection and graft thrombosis, both of which typically result in urgent graft hysterectomy. During pregnancy, one of our patients experienced abnormal placentation, though this was not thought to be related to uterus transplantation.5

The U.S. Uterus Transplant Consortium (USUTC) is a group of active programs that are sharing ideas and outcomes and advocating for continued research in this rapidly developing field. Uterine transplants require collaboration with transplant surgery, transplant medicine, infectious disease, gynecologic surgery, high-risk obstetrics, and other specialties. While significant progress has been made in a short period of time, uterine transplantation is still in its early stages, and transplants should be done in institutions that have the capacity for mentorship, bioethical oversight, and long-term follow-up of donors, recipients, and offspring.

The USUTC has recently proposed guidelines for nomenclature related to operative technique, vascular anatomy, and uterine transplantation outcomes.10 It proposes standardizing the names for the four veins originating from the uterus (to eliminate current inconsistency), which will be important as optimal strategies for vascular anastomoses are discussed and determined.

In addition, the consortium is creating a registry for the rigorous collection of data on procedures and outcomes (from menstruation and pregnancy through delivery, graft removal, and long-term follow-up). A registry has also been proposed by the International Society for Uterine Transplantation.

A major question remains in our field: Is the living-donor or deceased-donor uterus transplant the best approach? Knowledge of the quality of the uterus is greater preoperatively within a living-donor model, but no matter how minimally invasive the technique, the donor still assumes some risk of prolonged surgery and extensive pelvic dissection for a transplant that is not lifesaving.

On the other hand, deceased-donor transplants require additional layers of organization and coordination, and the availability of suitable deceased-donor uteri will likely not be sufficient to meet the current demand. Many of us in the field believe that the future of uterine transplantation will involve some combination of living- and deceased-donor transplants – similar to other solid organ transplant programs.

Dr. Flyckt and Dr. Richards reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures.

Correction, 2/2/21: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Richards' name in the photo caption.

References

1. Lancet. 2015;14:385:607-16.

2. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2019;10(1):23-5.

3. Transplantation. 2020;104(7):1312-5.

4. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(5):1270-4.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(2):143-51.

6. J Minimally Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:628-35.

7. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(9):1222-9.

8. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(1):183.

9. Fertil Steril. 2020 Jul 16. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.05.017

10 Am J Transplant. 2020;20(12):3319-25.