Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever

If a resistant microorganism and wound infection can be excluded, the clinician then must begin a diligent search for “zebras” (ie, uncommon but potentially serious causes of persistent fever).1,4 One possible cause is a pelvic abscess. These purulent collections typically form in the retrovesicle space as a result of infection of a hematoma that formed between the posterior bladder wall and the lower uterine segment, in the leaves of the broad ligament, or in the posterior cul-de-sac. The abscess may or may not be palpable. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, with a preponderance of neutrophils. The best imaging test for an abscess is a computed tomography (CT) scan. Abscesses require drainage, which usually can be accomplished by insertion of a percutaneous drain under ultrasonographic or CT guidance.

A second unusual cause of persistent fever is septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis. The infected venous emboli usually are present in the ovarian veins, with the right side predominant. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and the infected clots are best imaged by CT scan with contrast or magnetic resonance angiography. The appropriate treatment is continuation of broad-spectrum antibiotics and administration of therapeutic doses of parenteral anticoagulants such as enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin.

A third explanation for persistent fever is retained products of conception. This diagnosis is best made by ultrasonography. The placental fragments should be removed by sharp curettage.

A fourth consideration when evaluating the patient with persistent fever is an allergic drug reaction. In most instances, the increase in the patient’s temperature will correspond with administration of the offending antibiotic(s). Affected patients typically have an increased number of eosinophils in their peripheral white blood cell count. The appropriate management of drug fever is discontinuation of antibiotics.

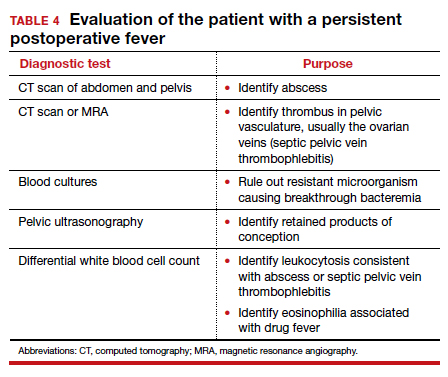

A final and distinctly unusual consideration is recrudescence of a connective tissue disorder such as systemic lupus erythematosus. The best test to confirm this diagnosis is the serum complement assay, which will demonstrate a decreased serum concentration of complement, reflecting consumption of this serum protein during the inflammatory process. The correct management for this condition is administration of a short course of systemic glucocorticoids. TABLE 4 summarizes a simple, systematic plan for evaluation of the patient with a persistent postoperative fever.

Preventive measures

We all remember the simple but profound statement by Benjamin Franklin, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” That folksy adage rings true with respect to postoperative infection because this complication extends hospital stay, increases hospital expense, and causes considerable discomfort and inconvenience for the patient. Therefore, we would do well to prevent as many instances of postoperative infection as possible.

Endometritis

On the basis of well-designed, prospective, randomized trials (Level 1 evidence), 3 interventions have proven effective in reducing the frequency of postcesarean endometritis. The first is irrigation of the vaginal canal preoperatively with an iodophor solution.5,6 The second is preoperative administration of systemic antibiotics.7-9 The combination of cefazolin (2 g IV within 30 minutes of incision) plus azithromycin (500 mg IV over 1 hour prior to incision) is superior to cefazolin alone.10,11 The third important preventive measure is removing the placenta by traction on the umbilical cord rather than by manual extraction.12,13

Wound infection

Several interventions are of proven effectiveness in reducing the frequency of postcesarean wound (surgical site) infection. The first is removal of hair at the incision site by clipping rather than by shaving (Level 2 evidence).14 The second is cleansing of the skin with chlorhexidine rather than iodophor (Level 1 evidence).15 The third is closing of the deep subcutaneous layer of the incision if it exceeds 2 cm in depth (Level 1 evidence).16,17 The fourth is closure of the skin with subcutaneous sutures rather than staples (Level 1 evidence).18 The monofilament suture poliglecaprone 25 is superior to the multifilament suture polyglactin 910 for this purpose (Level 1 evidence).19 Finally, in obese patients (body mass index >30 kg/m2), application of a negative pressure wound vacuum dressing may offer additional protection against infection (Level 1 evidence).20 Such dressings are too expensive, however, to be used routinely in all patients.

Urinary tract infection

The most important measures for preventing postoperative UTIs are identifying and clearing asymptomatic bacteriuria prior to delivery, inserting the urinary catheter prior to surgery using strict sterile technique, and removing the catheter as soon as possible after surgery, ideally within 12 hours.1,4

CASE Resolved

The 2 most likely causes for this patient’s poor response to initial therapy are resistant microorganism and wound infection. If a wound infection can be excluded by physical examination, the patient’s antibiotic regimen should be changed to metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). If an incisional abscess is identified, the incision should be opened and drained, and vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen. If a wound cellulitis is evident, the incision should not be opened, but vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen to enhance coverage against aerobic Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species. ●