Chemoprevention uptake in at-risk women

OBG Management: How does the risk assessment result influence the uptake of chemoprevention? Are more women willing to take preventive medication?

Dr. Pederson: We really never practice medicine using numbers. We use clinical judgment, and we use relationships with patients in terms of developing confidence and trust. I think that the uptake that we exhibit in our center probably is more based on the patients’ perception that we are confident in our recommendations. I think that many practitioners simply are not comfortable with explaining medications, explaining and managing adverse effects, and using alternative medications. While the modeling helps, I think the personal expertise really makes the difference.

Going forward, the addition of the polygenic risk score to the mathematical risk models is going to make a big difference. Right now, the mathematical risk model is simply that: it takes the traditional risk factors that a patient has and spits out a number. But adding the patient’s genomic data—that is, a weighted summation of SNPs, or single nucleotide polymorphisms, now numbering over 300 for breast cancer—can explain more about their personalized risk, which is going to be more powerful in influencing a woman to take medication or not to take medication, in my opinion. Knowing their actual genomic risk will be a big step forward in individualized risk stratification and increased medication uptake as well as vigilance with high risk screening and attention to diet, exercise, and drinking alcohol in moderation.

OBG Management: What drugs can be used for breast cancer preventive therapy, and how do you select a drug based on patient factors?

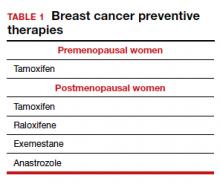

Dr. Pederson: The only drug that can be used in the premenopausal setting is tamoxifen (TABLE 1). Women can’t take it if they are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or if they don’t use a reliable form of birth control because it is teratogenic. Women also cannot take tamoxifen if they have had a history of blood clots, stroke, or transient ischemic attack; if they are on warfarin or estrogen preparations; or if they have had atypical endometrial biopsies or endometrial cancer. Those are the absolute contraindications for tamoxifen use.

Tamoxifen is generally very well tolerated in most women; some women experience hot flashes and night sweats that often will subside (or become tolerable) over the first 90 days. In addition, some women experience vaginal discharge rather than dryness, but it is not as bothersome to patients as dryness can be.

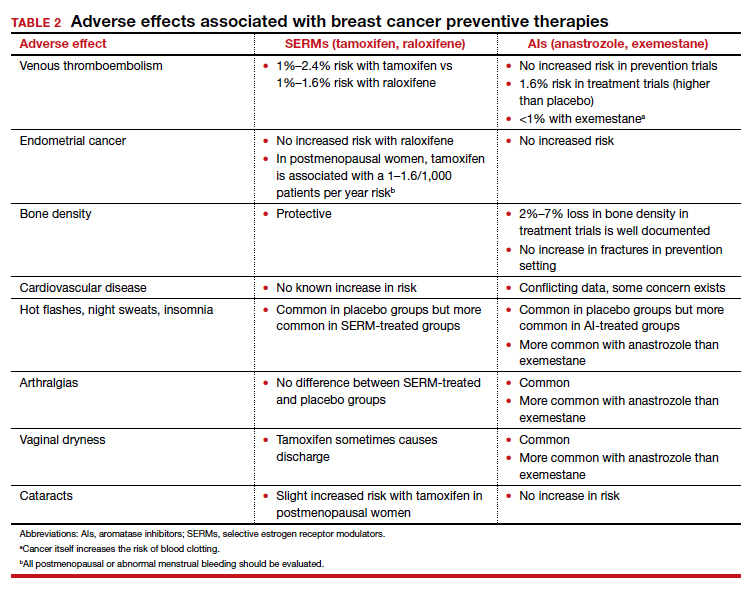

Tamoxifen can be used in the pre- or postmenopausal setting. In healthy premenopausal women, there’s no increased risk of the serious adverse effects that are seen with tamoxifen use in postmenopausal women, such as the 1% risk of blood clots and the 1% risk of endometrial cancer.

In postmenopausal women who still have their uterus, I’ll preferentially use raloxifene over tamoxifen. If they don’t have their uterus, tamoxifen is slightly more effective than the raloxifene, and I’ll use that.

Tamoxifen and raloxifene are both selective estrogen receptor modulators, or SERMs, which means that they stimulate receptors in some tissues, like bone, keeping bones strong, and block the receptors in other tissues, like the breast, reducing risk. And so you get kind of a two-for-one in terms of breast cancer risk reduction and osteoporosis prevention.

Another class of preventive drugs is the aromatase inhibitors (AIs). They block the enzyme aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogens peripherally; that is, the androgens that are produced primarily in the adrenal gland, but in part in postmenopausal ovaries.

In general, AIs are less well tolerated. There are generally more hot flashes and night sweats, and more vaginal dryness than with the SERMs. Anastrozole use is associated with arthralgias; and with exemestane use, there can be some hair loss (TABLE 2). Relative contraindications to SERMs become more important in the postmenopausal setting because of the increased frequency of both blood clots and uterine cancer in the postmenopausal years. I won’t give it to smokers. I won’t give tamoxifen to smokers in the premenopausal period either. With obese women, care must be taken because of the risk of blood clots with the SERMS, so then I’ll resort to the AIs. In the postmenopausal setting, you have to think a lot harder about the choices you use for preventive medication. Preferentially, I’ll use the SERMS if possible as they have fewer adverse effects.

OBG Management: What is the general duration of treatment with these risk-reducing drugs?

Dr. Pederson: All of them are recommended to be given for 5 years, but the MAP.3 trial, which studied exemestane compared with placebo, showed a 65% risk reduction with 3 years of therapy.3 So occasionally, we’ll use 3 years of therapy. Why the treatment recommendation is universally 5 years is unclear, given that the trial with that particular drug was done in 3 years. And with low-dose tamoxifen, the recommended duration is 3 years. That study was done in Italy with 5 mg daily for 3 years.4 In the United States we use 10 mg every other day for 3 years because the 5-mg tablet is not available here.

Continue to: Counseling points...