CASE 1 Pregnant patient endures extensive wait and travel times to have antenatal testing

Pregnant at age 35 without comorbidities, Ms. H was instructed to schedule weekly biophysical profiles (BPP) after 36 weeks’ gestation for advanced maternal age. She receives care at a community office 25 miles from the hospital where she will deliver. Ms. H must complete her antenatal testing at the hospital where the sonographer performs BPPs. She sees her physician at the nearby clinic and then takes public transit to the hospital. She waits 2 hours to be seen then makes her way back home. Her prenatal care visit, which usually takes 30 minutes, turns into a 5-hour ordeal. Ms. H delivered a healthy baby at 39 weeks. Unfortunately, she was fired from her job for missing too many workdays.

Antenatal testing has become routine, and it is costly

For the prescriber, antenatal testing is simple: Order a weekly ultrasound exam to reduce the risk of stillbirth, decrease litigation, generate income, and maximize patient satisfaction (with the assumption that everyone likes to peek at their baby). Recommending antenatal testing has—with the best intentions—become a habit and therefore is difficult to break. However, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recognizes that “there is a paucity of evidenced-based recommendations on the timing and frequency of antenatal fetal surveillance because of the challenges of conducting prospective trials in pregnancies complicated by stillbirths and the varying conditions that place pregnancies at high risk for stillbirth. As a result, evidence for the efficacy of antenatal fetal surveillance, when available, is largely circumstantial.”1

Antenatal testing without an evidence-based indication can be costly for the health care system, insurance companies, and patients. Many clinics, especially those in rural communities, do not have the equipment or personnel to complete antenatal testing on site. Asking a pregnant patient to travel repeatedly to another location for antenatal testing can increase her time off from work, complicate childcare, pose a financial burden, and lead to nonadherence. As clinicians, it is imperative that we work with our patients to create an individualized care plan to minimize these burdens and increase adherence.

Antenatal fetal surveillance can be considered for conditions in which stillbirth is reported more frequently than 0.8 per 1,000.

Advanced maternal age and stillbirth risk

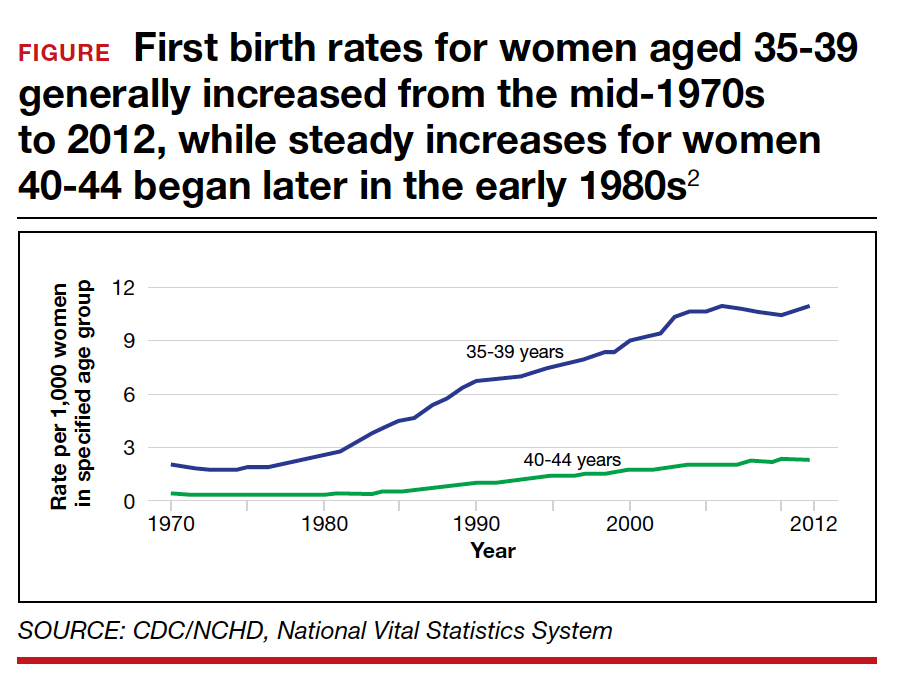

One of the most common reasons for antenatal testing is advanced maternal age, that is, age older than 35. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Vital Statistics System, from 2000 to 2012, 46 states and the District of Columbia (DC) reported an increase in first birth rates for women aged 35 to 39. Thirty-one states and DC saw a rise among women aged 40 to 44 in the same period (FIGURE).2

Advanced maternal age is an independent risk factor for stillbirth, with women aged 35 to 39 at 1.9-fold increased risk and women older than age 40 with a 2.4-fold higher risk compared with women younger than age 30.3 In a review of 44 studies including nearly 45,000,000 births, case-control studies, versus cohort studies, demonstrated a higher odds for stillbirth among women aged 35 and older (odds ratio [OR], 2.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.57-3.66 vs OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.6-1.87).4 Now, many women older than age 35 may have a concomitant risk factor, such as diabetes or hypertension, that requires antenatal testing. However, for those without other risk factors, nearly 863 antenatal tests and 71 inductions would need to be completed to reduce the number of stillbirths by 1. Antenatal testing for women older than age 35 without other risk factors should be individualized through shared decision making.5 See the ACOG committee opinion for a table that outlines factors associated with an increased risk of stillbirth and suggested strategies for antenatal surveillance after viability.1

Continue to: CASE 2 Patient with high BPP score and altered...