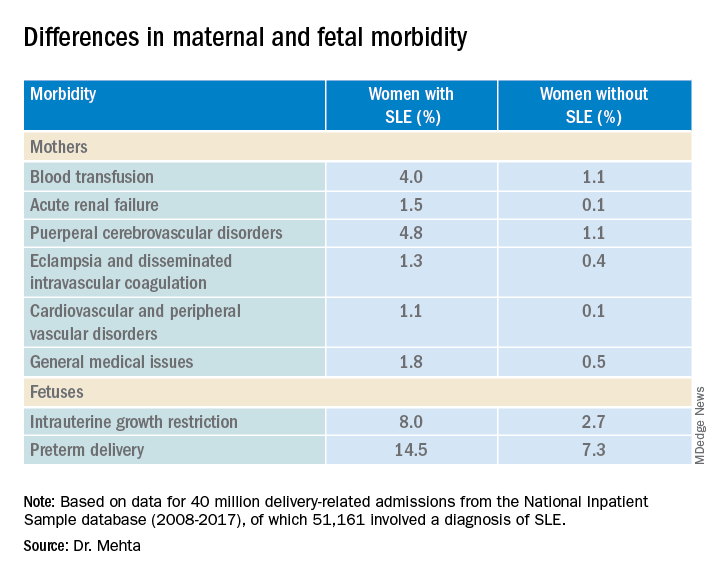

COPENHAGEN – Pregnant women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are at significantly higher risk of requiring transfusion, developing a cerebrovascular disorder, or developing acute renal failure than pregnant women without SLE, a review of data from an American national sample indicates.

Pregnant women with SLE also have a twofold-higher risk for premature delivery, and a threefold risk of having a fetus with intrauterine growth restriction than their pregnant counterparts without SLE, reported Bella Mehta, MBBS, MS, MD, a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York.

“Severe maternal morbidity and fetal morbidity still remain high, but this work can help inform physicians and counsel patients for pregnancy planning and management,” she said at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

Although in-hospital maternal and fetal mortality rates for women with SLE have declined over the past 2 decades, the same cannot be said for morbidities, prompting the investigators to conduct a study to determine the proportion of fetal and maternal morbidity in SLE deliveries, compared with non-SLE deliveries over a decade.

Inpatient Sample

Dr. Mehta and colleagues studied retrospective data on 40 million delivery-related admissions from the National Inpatient Sample database. Of these patients, 51,161 had a diagnosis of SLE.

They identified all delivery-related hospital admissions for patients with and without SLE from 2008 through 2017 using diagnostic codes.

The researchers looked at fetal morbidity indicators, including preterm delivery and intrauterine growth restriction, and used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention standard definition of severe maternal morbidity as “unexpected outcomes of labor and delivery that result in significant short- or long- term consequences to a woman’s health.”

They identified 21 severe maternal morbidity outcomes, including blood transfusion requirements, acute renal failure, eclampsia and disseminated intravascular coagulation, cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disorders, and general medical issues (hysterectomy, shock, sepsis, adult respiratory distress syndrome, severe anesthesia complications, temporary tracheostomy, and ventilation).

Study results

Women with SLE were slightly older at the time of delivery (mean age, 30.05 vs. 29.19 years) and had more comorbidities, according to the Elixhauser Comorbidity Scale, with 97.84% of women in this group having one to four comorbidities, compared with 19.4% of women without SLE.

Dr. Mehta acknowledged that the study was limited by the inability to capture outpatient deliveries, although she noted that only about 1.3% of deliveries in the United States occur outside the inpatient setting.

In addition, she noted that the database does not include information on lupus disease activity, Apgar scores, SLE flares, the presence of nephritis, antiphospholipid or anti-Ro/SSA antibodies, or medication use.

A rheumatologist who was not involved in the study said in an interview that the data from this study are in line with those in other recently published studies.

“The problem is that these data were not corrected for further disease activity or drugs,” said Frauke Förger, MD, professor of rheumatology and immunology at the University of Bern (Switzerland), who comoderated the oral abstract session where the data were presented.

She said prospective studies that adjusted for factors such as SLE disease activity and medication use will be required to give clinicians a better understanding of how to manage pregnancies in women with SLE.

The study was supported by an award from Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Mehta and Dr. Förger reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.