Before the introduction of insulin, there were few reported cases of pregnancy complicated by diabetes because women with the disease too often did not live to childbearing age, and when they did, they were often counseled to terminate their pregnancies. Perinatal and maternal mortality in the limited number of reported pregnancies were 70% and 40%, respectively,1 making the risks of continuing the pregnancy quite high.

After insulin became available, maternal mortality dropped dramatically, down to a few percent. Perinatal mortality also declined, but it took several decades to achieve a similar magnitude of reduction.2 Today, with insulin therapy and tight glucose control as well as improved perinatal care, almost all women with diabetes can contemplate pregnancy with greater hope for normal outcomes.

Problems persist, however. Maternal diabetes continues to cause a variety of adverse outcomes, including infants large for gestational age, prematurity, and structural birth defects. Birth defects and prematurity, in fact, are the top causes of the unacceptably high infant mortality rate in the United States – a rate that is about 70% higher than the average in comparable developed countries.3

Infant mortality is considered an indicator of population health and of the development of a country; to reduce its rate, we must address these two areas.

Women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes are five times more likely to have a child with birth defects than are nondiabetic women.4 Up to 10% of women with preexisting diabetes will have fetuses with a major congenital malformation.5

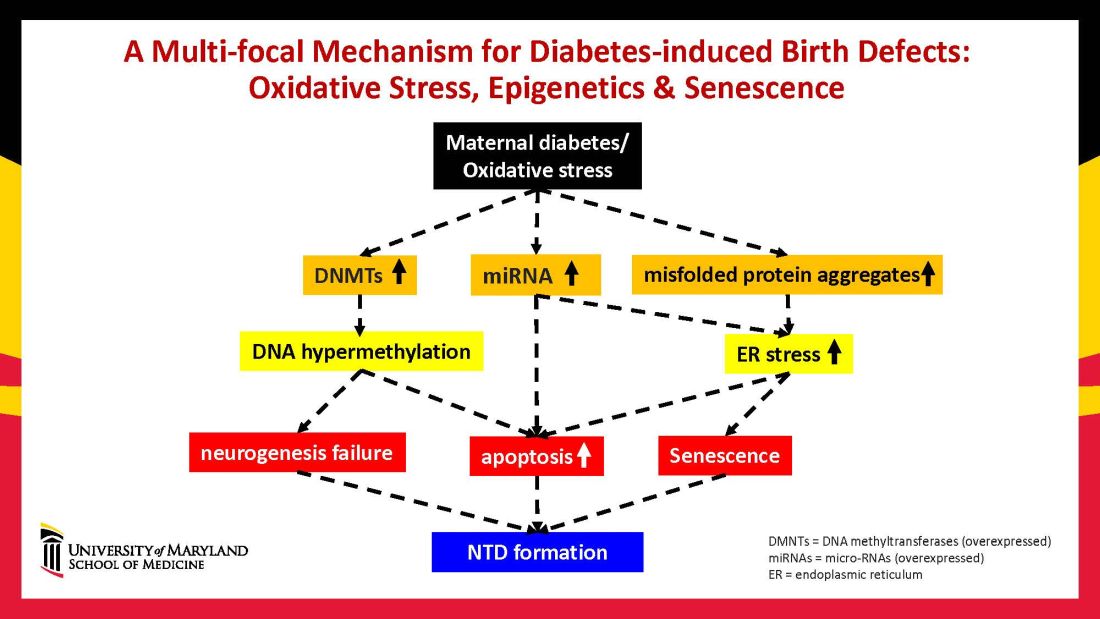

Over the years we have been striving in our Center for Birth Defects Research to understand the pathomechanisms and the molecular and epigenetic alterations behind the high rates of birth defects in the offspring of women with preexisting diabetes. We have focused on heart defects and neural tube defects (particularly the latter), which together cause significant mortality, morbidity, disability, and human suffering.

Using animal models that mimic human diabetic pregnancy, we have made significant strides in our understanding of the mechanisms, uncovering molecular pathways involving oxidative stress, senescence/premature cellular aging, and epigenetic modifications (Figure 1). Understanding these pathways is providing us, in turn, with potential therapeutic targets and approaches that may be used in the future to prevent birth defects in women who enter pregnancy with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.