Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) is a common cause of vaginitis and gynecologic morbidity in the United States and globally.1 RVVC is defined as at least 3 laboratory-confirmed (for example, culture, nucleic acid amplification test [NAAT]) symptomatic episodes in the previous 12 months.2 Common symptoms include vulvar pruritus, erythema, local skin and mucosal irritation, and abnormal discharge that may be thick and white or thin and watery.

The true incidence of RVVC is difficult to determine due to clinical diagnostic inaccuracy that results in over- and underdiagnosis of VVC and the general availability of over-the-counter topical antifungal medications that individuals who self-diagnose use to treat VVC.3

Causative organisms

Vulvovaginal yeast infections are caused by Candida species, a family of ubiquitous fungi that are a part of normal genitourinary and gastrointestinal flora.4 As such, these infections are commonly termed VVC. The presence of Candida species in the vagina without evidence of inflammation is not considered an infection but rather is more consistent with vaginal colonization. Inflammation in the setting of Candida species is what characterizes a true VVC infection.4

Candida albicans is responsible for the vast majority of VVC cases in the United States, with Candida glabrata accounting for most of the remaining infections.5 The majority of RVVC infections that are caused by C albicans are due to azole-sensitive strains (85%–95% of infections).2C glabrata, by contrast, is intrinsically resistant to azoles, which is thought primarily to be due to overexpression of drug efflux pumps that remove active drug from the cell.6,7

Why does VVC reoccur?

The pathogenesis of RVVC is not well understood. Predisposing factors may include frequent or recent antibiotic use, poorly controlled diabetes, immunodeficiency, and other host factors. However, many cases of RVVC are idiopathic and no predisposing or underlying conditions are identified.7

The role of genetic factors in predisposing to or triggering RVVC is unclear and is an area of ongoing investigation.2 Longitudinal DNA-typing studies suggest that recurrent disease is usually due to relapse from a persistent vaginal reservoir of organisms (that is, vaginal colonization) or endogenous reinfection with identical strains of susceptible C albicans.8,9 Symptomatic VVC likely results when the symbiotic balance between yeast and the normal vaginal microbiota is disrupted (by either Candida species overgrowth or changes in host immune factors).2 Less commonly, “recurrent” infections may in fact be due to azole-resistant Candida and non-Candida species.2

Clinical aspects and diagnosis of VVC

Signs and symptoms suggestive of VVC include vulvovaginal erythema, edema, vaginal discharge, vulvovaginal pruritus, and irritation. Given the lack of specificity of individual clinical findings in diagnosing VVC, or for distinguishing between other common causes of vaginitis (such as bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis), laboratory testing (that is, microscopy) should be performed in combination with a clinical exam in order to make a confident diagnosis of VVC.10 Self-diagnosis of VVC is inaccurate and is not recommended, as misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment is cost ineffective, delays accurate diagnoses, and may contribute to growing azole resistance.

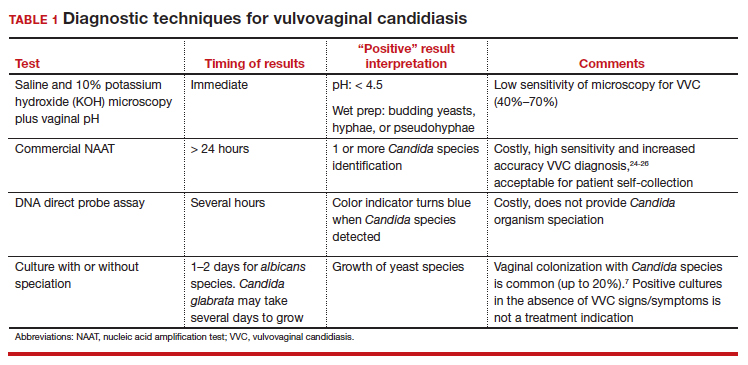

In patients with signs and symptoms of VVC, saline and potassium hydroxide microscopy should be performed.7 TABLE 1 summarizes other major diagnostic techniques for VVC.

Diagnostic considerations

Non-albicans Candida species, such as C glabrata, may be associated with minimally symptomatic or completely asymptomatic infections and may not be identified easily on wet mount as it does not form pseudohyphae or hyphae.11 Therefore, culture and susceptibility or NAAT testing is highly recommended for patients who remain symptomatic and/or have a nondiagnostic microscopy and a normal vaginal pH.7

Treatment options

Prior to May 2022, there had been no drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat RVVC. The mainstay of treatment is long-term maintenance therapy to achieve mycologic remission (TABLE 2).

In general, recurrent episodes of VVC should be treated with a longer duration of therapy (for example, oral fluconazole 150 mg every 72 hours for a total of 3 doses or topical azole for 7–14 days).7 If recurrent maintenance/suppressive therapy is started, the induction phase should be longer as well, at least 10 to 14 days with a topical or oral azole followed by a 6-month or longer course of weekly oral or topical azole therapy (such as 6–12 months).12,13

Patients with underlying immunodeficiency (such as poorly controlled diabetes, chronic corticosteroid treatment) may need prolonged courses of therapy. Correction of modifiable conditions and optimization of comorbidities should be prioritized—for example, optimized glucose control, weight loss, durable viral suppression, and so on. Of note, symptomatic VVC is more frequent among individuals with HIV and correlates with severity of immunodeficiency. Pharmacologic options for RVVC for individuals with HIV do not differ from standard recommendations.14

Fluconazole

Fluconazole is a safe, affordable, and convenient prescription oral medication that can be used for initial and maintenance/suppressive therapy.2 Fluconazole levels in vaginal secretions remain at therapeutic concentrations for at least 72 hours after a 150-mg dose.15 Induction therapy consists of oral fluconazole 150 mg every 72 hours for a total of 3 doses, followed by a maintenance regimen of a once-weekly dose of oral fluconazole 150 mg for a total of 6 months. Unfortunately, up to 55% of patients will experience a relapse in symptoms.12

Routine liver function test monitoring is not indicated for fluconazole maintenance therapy, but it should be performed if patients are treated with daily or long-term alternative oral azole medications, such as ketoconazole and itraconazole.

During pregnancy, only topical azole therapy is recommended for use, given the potential risk for adverse fetal outcomes, such as spontaneous abortion and congenital malformations, with fetal exposure to oral fluconazole ingested by the pregnant person.16 Fluconazole is present in breast milk, but it is safe to use during lactation when used at recommended doses.17

Continue to: Options for fluconazole-resistant C albicans infection...