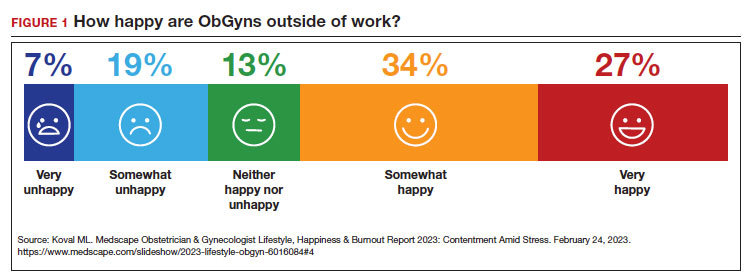

Physicians have some of the highest rates of burnout among all professions.1 Complicating matters is that clinicians (including residents)2 may avoid seeking treatment out of fear it will affect their license or privileges.3 In this article, we consider burnout in greater detail, as well as ways of successfully addressing the level of burnout in the profession (FIGURE 1), including steps individual practitioners, health care entities, and regulators should consider to reduce burnout and its harmful effects.

How burnout becomes a problem

Six general factors are commonly identified as leading to clinician career dissatisfaction and burnout:4

1. work overload

2. lack of autonomy and control

3. inadequate rewards, financial and otherwise

4. work-home schedules

5. perception of lack of fairness

6. values conflict between the clinician and employer (including a breakdown of professional community).

At the top of the list of causes of burnout is often “administrative and bureaucratic headaches.”5 More specifically, electronic health records (EHRs), including computerized order entry, is commonly cited as a major cause of burnout.6,7 According to some studies, clinicians spend as much as 49% of working time doing clerical work,8 and studies found the extension of work into home life.9

Increased measurement of performance metrics in health care services are a significant contributor to physician burnout.10 These include pressure to see more patients, perform more procedures, and respond quickly to patient requests (eg, through email).7 As we will see, medical malpractice cases, or the risk of such cases, have also played a role in burnout in some medical specialties.11 The pandemic also contributed, at least temporarily, to burnout.12,13

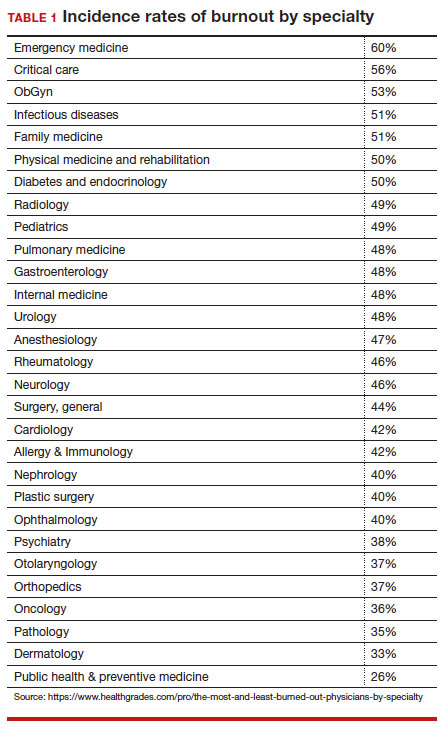

Rates of burnout among physicians are notably higher than among the general population14 or other professions.6 Although physicians have generally entered clinical practice with lower rates of burnout than the general population,15 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) reports that 40% to 75% of ObGyns “experience some form of professional burnout.”16,17 Other source(s) cite that 53% of ObGyns report burnout (TABLE 1).

Code QD85

Burnout is a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by 3 dimensions:

- feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion

- increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job

- a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment. Burn-out refers specifically to phenomena in the occupational context and should not be applied to describe experiences in other areas of life. Exclusions to burnout diagnosis include adjustment disorder, disorders specifically associated with stress, anxiety or fear-related disorders, and mood disorders.

Reference

1. International Classification of Diseases Eleventh Revision (ICD-11). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2022.

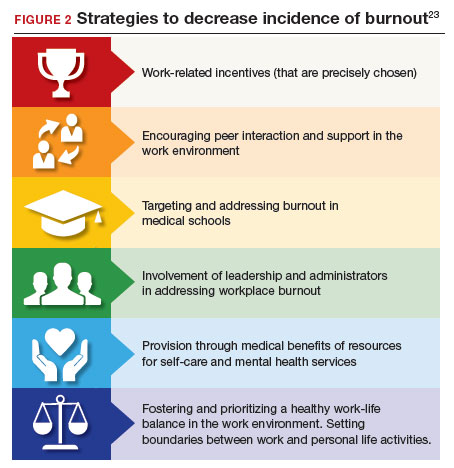

Burnout undoubtedly contributes to professionals leaving practice, leading to a significant shortage of ObGyns.18 It also raises several significant legal concerns. Despite the enormity and seriousness of the problem, there is considerable optimism and assurance that the epidemic of burnout is solvable on the individual, specialty, and profession-wide levels. ACOG and other organizations have made suggestions for physicians, the profession, and to health care institutions for reducing burnout.19 This is not to say that solutions are simple or easy for individual professionals or institutions, but they are within the reach of the profession (FIGURE 2).

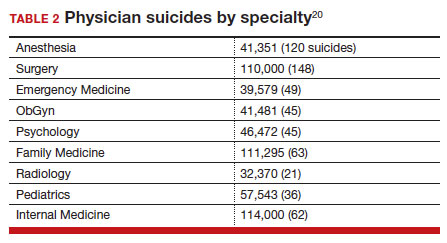

Suicide among health care professionals is one other concern (TABLE 2)20 and theoretically can stem from burnout, depression, and other psychosocial concerns.

Costs of clinician burnout

Burnout is endemic among health care providers, with numerous studies detailing the professional, emotional, and financial costs. Prior to the pandemic, one analysis of nationwide fiscal costs associated with burnout estimated an annual cost of $4.6B due to physician turnover and reduced clinical hours.21 The COVID-19 epidemic has by all accounts worsened rates of health care worker burnout, particularly for those in high patient-contact positions.22

Female clinicians appear to be differentially affected; in one recent study women reported symptoms of burnout at twice the rate of their male counterparts.23 Whether burnout rates will return to pre-pandemic levels remains an open question, but since burnout is frequently related to one’s own assessment of work-life balance, it is possible that a longer term shift in burnout rates associated with post-pandemic occupational attitudes will be observed.

Combining factors contribute to burnout

Burnout is a universal occupational hazard, but extant data suggest that physicians and other health care providers may be at higher risk. Among physicians, younger age, female gender, and front-line specialty status appear associated with higher burnout rates.24 Given that ObGyn physicians are overwhelmingly female (60% of physicians and 86% of residents),25,26 gender-related burnout factors exist alongside other specific occupational burnout risks. While gender parity has been achieved among health care providers, gender disparities persist in terms of those in leadership positions, compensation, and other factors.22

The smattering of evidence suggesting that ObGyns have higher rates of burnout than many other specialties is understandable given the unique legal challenges confronting ObGyn practice. This may be of special significance because ObGyn malpractice insurance rates are among the highest of all specialties.27 The overall shortage of ObGyns has been exacerbated by the demonstrated negative effects on training and workforce representation stemming from recent legislation that has the effect of criminalizing certain aspects of ObGyn practice;28 for instance, uncertainty regarding abortion regulations.

These negative effects are particularly heightened in states in which the law is in flux or where there are continuing efforts to substantially limit access to abortion. The efforts to increase civil and even criminal penalties related to abortion care challenge ObGyns’ professional practices, as legal rules are frequently changing. In some states, ObGyns may face additional workloads secondary to a flight of ObGyns from restrictive jurisdictions in addition to legal and professional repercussions. In a small study of 19 genetic counselors dealing with restrictive legislation in the state of Ohio,29 increased stress and burnout rates were identified as a consequence of practice uncertainties under this legislation. It is certain that other professionals working in reproductive health care are similarly affected.30

The programs provide individual resources to providers in distress, periodically survey initiatives at Stanford to assess burnout at the organizational level, and provide input designed to spur organizational change to reduce the burden of burnout. Ways that they build community and connections include:

- Live Story Rounds events (as told by Stanford Medicine physicians)

- Commensality Groups (facilitated small discussion groups built around tested evidence)

- Aim to increase sense of connection and collegiality among physicians and build comradery at work

- CME-accredited physician wellness forum, including annual doctor’s day events

Continue to: Assessment of burnout...