Who is at risk

Congenital CMV, which occurs in 2.1 to 7.7 per 10,000 live births in the United States, is both the most common congenital infection and the leading cause of nonhereditary congenital hearing loss in children.4,5 The main reservoir of CMV in the United States is young children in day care settings, with approximately 50% of this population showing evidence of viral shedding in saliva.1 Adult populations in North America have a high prevalence of CMV IgG antibodies indicative of prior infection, with rates reaching 50% to 80%. Among seronegative individuals aged 12 to 49, the rate of seroconversion is approximately 1 in 60 annually.6 Significant racial disparities have been noted in rates of seroprevalence and seroconversion, with higher rates of infection in non-Hispanic Black and Mexican American individuals.6 Overall, the rate of new CMV infection among pregnant women in the United States is 0.7% to 4%.7

Clinical manifestations

Manifestations of infection differ depending on whether or not infection is primary or recurrent (secondary) and whether or not the host is immunocompetent or has a compromised immune system. Unique manifestations develop in the fetus.

CMV infection in children and adults. Among individuals with a normal immune response, the typical course of CMV is either no symptoms or a mononucleosis-like illness. In symptomatic patients, the most common symptoms include malaise, fever, and night sweats, and the most common associated laboratory abnormalities are elevation in liver function tests and a decreased white blood cell count, with a predominance of lymphocytes.8

Immunocompromised individuals are at risk for significant morbidity and mortality resulting from CMV. Illness may be the result of reactivation of latent infection due to decreased immune function or may be acquired as a result of treatment such as transplantation of CMV-positive organs or tissues, including bone marrow. Virtually any organ system can be affected, with potential for permanent organ damage and death. Severe systemic infection also can occur.

CMV infection in the fetus and neonate. As noted previously, fetal infection develops as a result of transplacental passage coincident with maternal infection. The risk of CMV transmission to the fetus and the severity of fetal injury vary based on gestational age at fetal infection and whether or not maternal infection is primary or secondary.

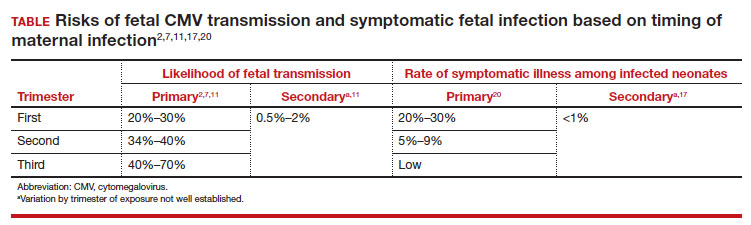

In most studies, primary maternal infections are associated with higher rates of fetal infection and more severe fetal and neonatal disease manifestations.2,7,9,10 Primary infections carry an overall 30% to 40% risk of transmission to the fetus.7,11 The risk of fetal transmission is much lower with a recurrent infection and is usually less than 2%.11 Due to their greater overall incidence, secondary infections account for the majority of cases of fetal and neonatal CMV disease.7 Importantly, although secondary infections generally have been regarded as having a lower risk and lower severity of fetal and neonatal disease, several recent studies have demonstrated rates of complications similar to, and even exceeding, those of primary infections.12-15 The TABLE provides a summary of the risks of fetal transmission and symptomatic fetal infection based on trimester of pregnancy.2,11,16-18

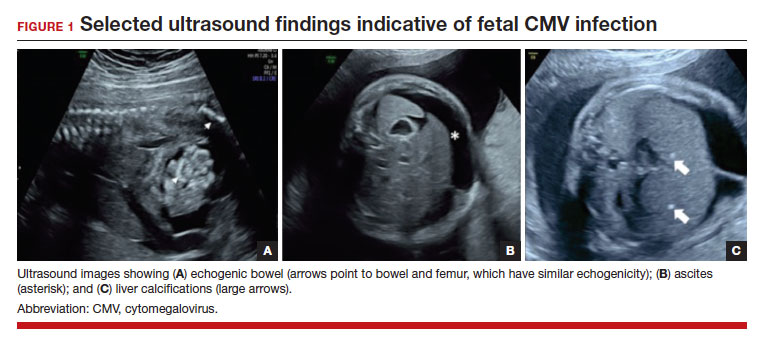

In the fetus, CMV may affect multiple organ systems. Among sonographic and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, central nervous system (CNS) anomalies are the most common.19,20 These can include microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, and periventricular calcifications. The gastrointestinal system also is frequently affected, and findings include echogenic bowel, hepatosplenomegaly, and liver calcifications. Lastly, isolated effusions, placentomegaly, fetal growth restriction, and even frank hydrops can develop. More favorable neurologic outcomes have been demonstrated in infants with no prenatal brain imaging abnormalities.20,21 However, the role of MRI in prenatal prognosis currently is not well defined.

FIGURE 1 illustrates selected sonographic findings associated with fetal CMV infection.

About 85% to 90% of infants with congenital CMV that results from primary maternal infection have no symptoms at birth. Among the 10% to 15% of infants that do have symptoms, petechial rash, jaundice, and hepatosplenomegaly are the most common manifestations (“blueberry muffin baby”). Approximately 10% to 20% of infants in this group have evidence of chorioretinitis on ophthalmologic examination, and 50% show either microcephaly or low birth weight.22Among survivors of symptomatic congenital CMV, more than 50% have long-term neurologic morbidities that may include sensorineural hearing loss, seizures, vision impairment, and developmental disabilities. Note that even when neonates appear asymptomatic at birth (regardless of whether infection is primary or secondary), 5% may develop microcephaly and motor deficits, 10% go on to develop sensorineural hearing loss, and the overall rate of neurologic morbidity reaches 13% to 15%.12,23 Some of the observed deficits manifest at several years of age, and, currently, no models exist for prediction of outcome.

Continue to: Diagnosing CMV infection...