Breast cancer represents the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the nation.1 However, unlike other cancers, most breast cancers are identified at stage I and have a 90% survival rate 5-year prognosis.2 These outcomes are attributable to various factors, one of the most significant being screening mammography—a largely accessible, highly sensitive and specific screening tool.3 Data demonstrate that malignant tumors detected on screening mammography have more favorable profiles in tumor size and nodal status compared with symptomatic breast cancers,4 which make it critical for early diagnosis. Most importantly, the research overwhelmingly demonstrates that screening mammography decreases breast cancer–related mortality.5-7

The USPSTF big change: Mammography starting at age 40 for all recommended

Despite the general accessibility and mortality benefits of screening mammography (in light of the high lifetime 12% prevalence of breast cancer in the United States8), recommendations still conflict across medical societies regarding optimal timing and frequency.9-12 Previously, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended that screening mammography should occur at age 50 biennially and that screening between ages 40 and 49 should be an individualized decision.13,14 In the draft recommendation statement issued on May 9, 2023, however, the USPSTF now recommends screening every other year starting at age 40 to decrease the risk of dying from breast cancer.15

This change represents a critically important shift. The new guidance:

- acknowledges the increasing incidence of early-onset breast cancer

- reinforces a national consciousness toward screening mammography in decreasing mortality,17 even among a younger age group for whom the perception of risk may be lower.

The USPSTF statement represents a significant change in how patients should be counseled. Practitioners now have more direct guidance that is concordant with what other national medical organizations offer or recommend, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American College of Radiology (ACR), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).

However, while the USPSTF statement can and should encourage health care practitioners to initiate mammography earlier than prior recommendations, ongoing discussion regarding the optimal screening interval is warranted. The USPSTF recommendations state that mammography should be performed biennially. While the age at initiation represents a step in the right direction, this recommended screening interval should be reevaluated.

Annual vs biennial screening?

The debate between annual and biennial screening mammography is not new. While many randomized trials on screening mammography have evaluated such factors as breast cancer mortality by age or rate of false positives,18 fewer trials have evaluated the optimal screening interval.

One randomized trial from the United Kingdom evaluated 99,389 people aged 50 to 62 from 1989 to 1996 who underwent annual screening (study arm) versus 3 years later (control).19 Findings demonstrated a significantly smaller tumor size in the study arm (P=.05) as well as an increased total cancer detection rate. However, the authors concluded that shortening the screening interval (from 3 years) would not yield a statistically significant decrease in mortality.19

In a randomized trial from Finland, researchers screened those aged older than 50 at biennial intervals and those aged younger than 50 at either annual or triennial intervals.20 Results demonstrated that, among those aged 40 to 49, the frequency of stage I cancers was not significantly different from screen-detected cancers, interval cancers, or cancers detected outside of screening (50%, 42%, and 44%, respectively; P=.73). Furthermore, there was a greater likelihood of interval cancers among those aged 40 to 49 at 1-year (27%) and 3-year (39%) screening intervals compared with those aged older than 50 screened biennially (18%; P=.08 and P=.0009, respectively).20

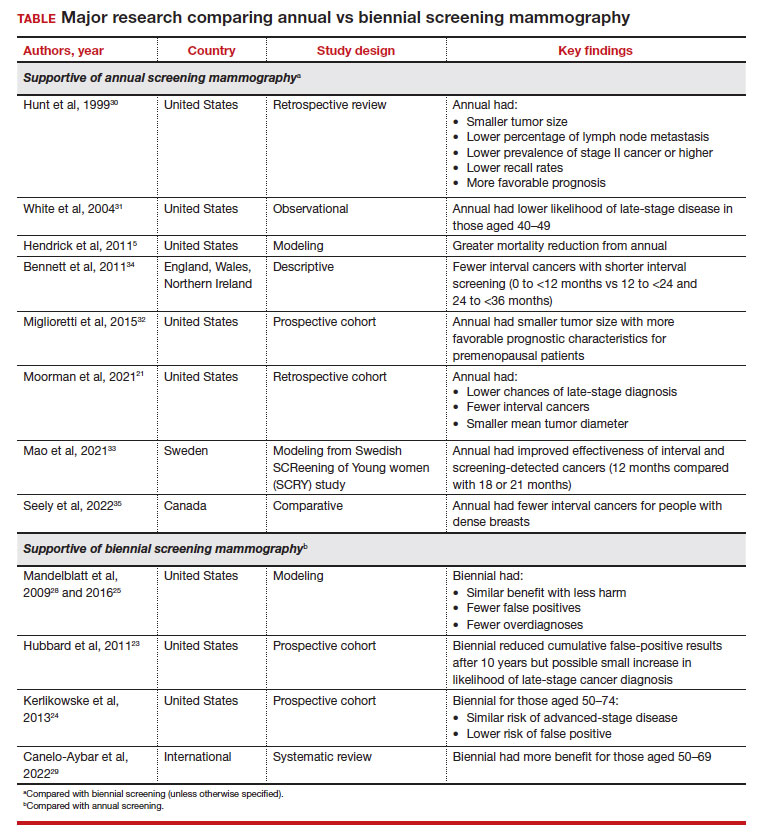

These randomized trials, however, have been scrutinized because of factors such as discrepancies in screening intervals by country as well as substantial improvements made in screening mammography since the time these trials were conducted.5 Due to the dearth of more contemporary randomized controlled trials accounting for more up-to-date training and technology, most of the more recent data has been largely observational, retrospective, or used modeling.21 The TABLE outlines some of the major studies on this topic.

False-positive results, biopsy rates. The arguments against more frequent screening include the possibility of false positives that require callbacks and biopsies, which may be more frequent among those who undergo annual mammography.22 A systematic review from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium demonstrated a 61.3% annual (confidence interval [CI], 59.4%–63.1%) versus 41.6% biennial (CI, 40.6%–42.5%) false-positive rate, resulting in a 7% (CI, 6.1%–7.8%) versus 4.8% (CI, 4.4–5.2%) rate of biopsy, respectively.23 This false-positive rate, however, also may be increased in younger patients aged 40 to 49 and in those with dense breasts.22,24 These callbacks and biopsies could induce significant patient stress, pain, and anxiety, as well as carry financial implications related to subsequent diagnostic imaging.

Overdiagnosis. There is also the risk of overdiagnosis, in which an indolent breast cancer that otherwise would not grow or progress to become symptomatic is identified. This could lead to overtreatment. While the exact incidence of overdiagnosis is unclear (due to recommendations for universal treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ), some data suggest that overdiagnosis could be decreased with biennial screening.25

While discomfort could also be a barrier, it may not necessarily be prohibitive for some to continue with future screening mammograms.22 Further, increased radiation with annual mammography is a concern. However, modeling studies have shown that the mortality benefit for annual mammography starting at age 40 outweighs (by 60-fold) the mortality risk from a radiation-induced breast cancer.26

Benefit from biennial screening

Some research suggests overall benefit from biennial screening. One study that used Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) breast cancer microsimulation was adapted to measure the incidence, mortality, and life-years gained for Canadian patients.27 This model demonstrated that mortality reduction was linked to greater lifetime screens for breast cancer, but this applied primarily to patients aged 50 and older. Overall, a larger impact was observed by initiating screening at age 40 than by decreasing screening intervals.27

Using modeling, Mandelblatt and colleagues demonstrated that biennial screening could capture most of the benefit of annual screening with less harm.28 In another study in 2016, Mandelblatt and colleagues used updated and revised versions of these simulation models and maintained that biennial screening upheld 79.8% to 81.3% of the benefits of annual screening mammography but with fewer overdiagnoses and false-positive results.25 The authors concluded that while biennial screening is equally effective for average-risk populations, there should be an evaluation of benefits and harms based on the clinical scenario (suggesting that annual screening for those at age 40 who carried elevated risk was similar to biennial screening for average-risk patients starting at age 50).25

Another study that served to inform the European Commission Initiative on Breast Cancer recommendations evaluated randomized controlled trials and observational and modeling studies that assessed breast screening intervals.29 The authors concluded that each screening interval has risks and benefits, with data suggesting more benefit with biennial screening for people aged 50 to 69 years and more possible harm with annual screening in younger people (aged 45–49).29

Continue to: Benefit from annual screening...