- Diagnostic categories of subfertility include oligospermia; azoospermia; minimal/mild or moderate/severe endometriosis; bilateral tubal occlusion; partial tubal defects; and unexplained subfertility.

- The duration of a couple’s subfertility, the age of the female partner, and whether the partnership has produced a prior pregnancy form the basis of their prognosis for live birth independent of treatment.

- If a couple fails to conceive within 3 to 6 treatment cycles after ovulation induction, further diagnostic evaluation is recommended.

- The accurate assessment by endometrial biopsy of luteal-phase sufficiency may be impossible in some women.

- In most cases, postcoital testing should be abandoned.

A 35-year-old nullipara who has not conceived after 2 years of unprotected intercourse presents for treatment. Her primary desire—apart from becoming pregnant—is obtaining a truthful estimate of her prognosis. Obviously, that is our priority as well, since appropriate treatment can be determined only when the prognosis is clearly defined.

Of course, we informally estimate patients’ prognoses every day based on their history, physical examination, and laboratory studies. But when it comes to fertility—particularly when the woman is over 30 years of age—a quantified estimate is vital. Here, we outline the steps involved in evaluating a couple for “subfertility” and offer a model for predicting prognosis as precisely as possible. We base our recommendations on guidelines from the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) and the American Urologic Association (AUA).1,2 We also searched Cochrane systematic reviews and MEDLINE English-language articles published between October 1, 1991, and October 1, 2001 (using the key words “infertility,” “prognosis,” and “diagnosis”), as well as the November 8, 2001, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. The prediction model itself originated with Collins and colleagues and Snick et al. 3,4

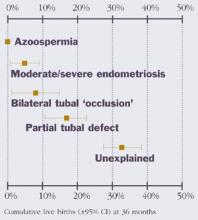

Diagnostic categories of subfertility include oligospermia; azoospermia; mild, moderate, or severe endometriosis; bilateral tubal occlusion; partial tubal defects; and unexplained subfertility. Of these, unexplained subfertility carries the best prognosis for spontaneous pregnancy and live birth, while oligospermia and mild endometriosis have an “intermediate” prognosis. The other categories have a poorer prognosis relative to unexplained subfertility (Figure 1). A failure to diagnose these problems will delay appropriate treatment.

FIGURE 1 Chance of live birth by diagnostic category

1 Basics: the history and physical

A thorough history and physical are the starting point, with special attention focused on signs and symptoms that suggest “a specific cause for infertility and thereby help to direct subsequent diagnostic evaluation.”1 An example would be a woman with irregular menstrual cycles and findings of hirsutism. The history is critical and should emphasize the following questions:3

- How long has the couple been subfertile?

- Has the partnership produced a prior pregnancy?

- How young is the female partner?

The answers to these questions form the basis of the couple’s prognosis for live birth independent of treatment. The prognosis is poorer if the woman already has been treated by other physicians.3,4 The baseline prognosis also declines with advancing maternal age and the duration of subfertility.3,4

The male partner also should be screened if the couple has failed to conceive after 1 year of unprotected intercourse.2 An atypical reproductive history or semen analysis is sufficient reason to refer him to a urologist or other specialist for full evaluation.2

Interestingly, abnormalities detected during the physical had no effect on the probability of conceiving in one study of 960 couples.5 On an individual basis, however, physical findings may be highly predictive of subfertility if disorders such as a congenital absence of the vas are discovered.

2 Assess ovulation

Ovulatory factors are a critical part of evaluation. If findings suggest ovulatory dysfunction, further testing will be necessary—possibly including an appraisal of ovarian reserve.1 Interventions aimed at restoring or improving ovulation should be closely monitored. If the couple fails to conceive within 3 to 6 treatment cycles, further diagnostic evaluation is recommended or—if evaluation is complete—another conception strategy should be tried.1

The guidelines suggest assessing ovulatory function by using one or more of the following methods:1

- Menstrual history

- Basal body temperature (BBT). However, it cannot reliably define the time of ovulation

- Serum progesterone. Midluteal-phase values exceeding 3 ng/mL are presumptive evidence of ovulation.

- Urinary luteinizing hormone (LH). Results generally correlate well with the peak in serum LH, particularly in evening urine specimens. However, the accuracy, reliability, and ease of use vary among tests.

- Endometrial biopsy. Histologic examination can confirm secretory endometrial development, although the accuracy of the criteria used to diagnose luteal-phase defects is questionable. In fact, the accurate assessment by endometrial biopsy of luteal-phase sufficiency may be impossible in some cases, owing to intercycle differences in progesterone production, variations in sampling sites, and interobserver differences in histologic assessment.6

- Serial transvaginal sonography (TVS). This detects evidence of ovulation by noting the disappearance of the dominant follicle.

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). This is for women with oligo-ovulation and should be measured with prolactin.

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). This diagnoses premature ovarian failure or hypothalamic amenorrhea in amenorrheic women.

- Cycle day 3 FSH. Also known as the clomiphene-challenge test, this is for women over 35 or with previous oophorectomy. Screening for ovarian reserve will not predict fecundity in the general population of subfertile women with ovulatory menstrual cycles.7 However, screening for ovarian reserve with a day 2-3 serum FSH level is useful for women such as our patient (age >35 years, history of poor ovarian response, or previous oophorectomy).1