DR. LUCENTE: We often use mesh and are more than simply content with our results—we are extremely pleased, and so are our patients. Having said that, our techniques have definitely evolved over the past few years, as we’ve focused on how to decrease exposure and, more recently, optimize sexual function and vaginal comfort.

First, to avoid exposure, the most critical step is precise hydrodissection and distention of the true vesicovaginal space. This step can only be achieved through careful tactile guidance of the needle tip into the space, where it should remain while hydrodissection is performed. Always remember, sharp dissection “follows” hydrodissection. If you place the needle bevel within the vaginal wall, you will “split” the vaginal wall—as during standard colporrhaphy—which will lead to a high exposure rate.

Second, to avoid dyspareunia, it’s essential to pay close attention to POP-Q measurements, especially vaginal length, to ensure that the reconstruction restores the same length without foreshortening. This approach entails leaving the cervix in most patients who have a shorter vagina, and making sure that the mesh is secured above the ischial spine in younger, sexually active patients who have demonstrated a higher risk of postoperative deep, penetrating dyspareunia, compared with older, less sexually active patients.

Also paramount is to ensure that you have manually displaced the vagina inwardly as much as possible before deploying or setting the mesh. If you simply try to suture secure the mesh with the vagina incised open, without the ability to deploy the mesh with a closed, displaced vagina (to mimic deep penetration), it is difficult, if not impossible, to properly set the mesh for optimal comfort.

In the early days of midurethral pubovaginal slings using polypropylene, the adage was “looser is better than tighter.” This is even truer for transvaginal mesh.

DR. KARRAM: Dr. Walters, please describe your current surgical procedure of choice without mesh and explain why you haven’t adopted mesh for routine repairs.

DR. WALTERS: About 20% of my prolapse surgeries—usually for posthysterectomy or recurrent vaginal vault prolapse—involve ASC with placement of polypropylene mesh. I perform most of these cases through a Pfannenstiel incision, but I’ve also done them laparoscopically. Several of my partners perform ASC laparoscopically and robotically.

For the other 80% of my patients who have prolapse, I perform repairs transvaginally, usually using high bilateral uterosacralligament vaginal-vault suspension. We have learned to suture higher and slightly more medial on the uterosacral ligaments to attain greater vaginal depth and minimize ureteral obstruction. We use two or three sutures on each uterosacral ligament, usually a combination of permanent and delayed absorbable sutures.

I am also performing more sacrospinous ligament suspensions because this operation is being studied by the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Properly performed, it is an excellent surgery for apical prolapse. But, as with most of our surgeries for prolapse, recurrent anterior wall prolapse remains a problem.

Like you, Dr. Karram, we’ve studied our group’s anatomic and functional outcomes very carefully for more than 10 years and are mostly satisfied with our cure and complication rates. Although our anatomic outcomes with these surgeries are not always perfect, our reoperation rate for prolapse is only about 5%, with a high level of satisfaction in 88% to 92% of patients.

DR. RAZ: Unaugmented reconstruction fails in more than 30% of cases. Some patients who have significant prolapse and attenuated tissue think that this tissue will become healthier or stronger after reconstructive surgery, but that isn’t the case. In these situations, excision and plication make no clinical sense.

The problem is that we have yet to identify the ideal surrogate for poor-quality tissue. Most of us use polypropylene mesh in different variations. We need a better material that will be nonimmunogenic, well tolerated, and easily incorporated without erosion. Xenograft-like derivatives of dermis, or allografts such as cadaveric fascia, have failed over the long term because the body reabsorbs the graft without forming any new connective tissue.

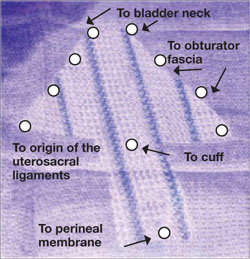

FIGURE 3 Mesh can be cut in the OR to custom-fit a patient

Hand-cut mesh and points of placement.

PHOTO: SHLOMO RAZ, MD

Is a kit a valuable aid?

DR. KARRAM: If a surgeon wants to augment a repair, what are the advantages of a packaged mesh kit, compared with simply cutting the mesh and performing surgery without a kit?

DR. WALTERS: The advantages of a packaged mesh kit are the convenience involved and the ability to consistently perform the same operation with the same product. That facilitates learning, teaching, and research. It also helps us understand the published literature a little better because “custom” prolapse repairs are operator-dependent and difficult to apply generally to a population of surgeons.