Think breast cancer survivors are unlikely to show up in your practice? You should think again.

At last official count, 2.5 million women in the United States had a history of breast cancer.1 Most of them are now free of malignancy, but others are still grappling with the disease in some form or fashion.2 All need continuing health care.

Roughly two thirds of women who have breast cancer have disease that is hormone-receptor–positive.2,3 Recently updated guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommend that adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women who have hormone-positive breast cancer include an aromatase inhibitor (AI) (see a summary of these guidelines on page 36). That makes it likely that a good number of breast cancer survivors who visit your practice are taking one of these medications: anastrozole (Arimidex), letrozole (Femara), or exemestane (Aromasin). These drugs are antiestrogens, given to postmenopausal women to reduce the likelihood of disease recurrence and progression.

The antiestrogenic properties of these drugs are what make them lifesavers. But the same qualities can create a range of health issues, from increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture to vasomotor and joint symptoms. And although ObGyns are not the physicians who prescribe these drugs, you may be the provider one of these women consults about their side effects and related issues.

To find out the latest on the management of women who are taking one of these agents, we inserted ourselves into the busy schedule of Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, who agreed to address some fundamental—and some not so basic—questions about the drugs. In this extended Q&A, Dr. Kaunitz touches on mechanism of action, benefits versus risks, common side effects, compliance with therapy, and the ill effects of early discontinuation.

Aromatase inhibitors are better than tamoxifen at reducing the risk of breast cancer recurrence in postmenopausal women who have hormone-receptor–positive disease. But, they increase the risk of osteoporosis and fracture and often cause arthralgias and other complaints that ObGyn practitioners may be called upon to manage.

OBG Management: What is the overall aim of adjuvant endocrine therapy in the setting of breast cancer?

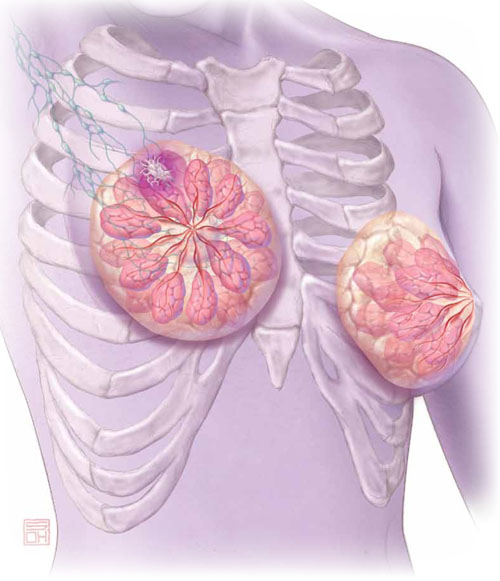

Dr. Kaunitz: Endocrine therapy—specifically, use of an AI—prevents the stimulation of breast cancer cells by endogenous estrogen. In other words, aromatase inhibitors suppress the growth of cancer cells that have estrogen receptors. These drugs also inhibit aromatase near any breast tumor and reduce estrogen levels in breast tissue.

OBG Management: What is the mechanism of action of adjuvant endocrine therapy?

Dr. Kaunitz: In postmenopausal women, androgens are converted to estrogens via the aromatase enzyme, which is present in adipose tissue and other sites. By blocking this enzyme, AIs reduce endogenous estrogen levels by as much as 95%.4

OBG Management: How does that differ from the mechanism of action of tamoxifen, another drug used in breast cancer patients?

Dr. Kaunitz: Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). It blocks estrogen in breast tissue selectively, by competitively binding to estrogen receptors.5 However, tamoxifen has estrogenic effects in the uterus, bone, and liver, as well as other tissues.

The efficacy of AIs in preventing breast cancer recurrence in the first 2 years after breast cancer surgery is higher than that of tamoxifen. And unlike tamoxifen, the AIs do not increase the risk of venous thromboembolism or cause endometrial disease.

OBG Management: What effects do aromatase inhibitors have in premenopausal women?

Dr. Kaunitz: These agents are not recommended for use in premenopausal women because, in that population, the lion’s share of estrogen production takes place in the ovary rather than in adipose tissue and muscle. If you were to administer an AI to a premenopausal woman, the reduced hypothalamic and pituitary estrogen feedback could lead to ovarian stimulation—which could increase ovarian steroid production.

OBG Management: What about women who become amenorrheic as a result of chemotherapy or other cancer treatment? Do most oncologists assume that they are postmenopausal and prescribe an aromatase inhibitor?

Dr. Kaunitz: Clinicians should not assume that chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea signals permanent cessation of ovarian function. It is common for ovarian function to return in this setting. Accordingly, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol levels should be assessed before an AI is considered as adjuvant therapy. Some investigators have suggested that the use of an AI in women who have chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea may actually increase the likelihood that ovarian function will return.6