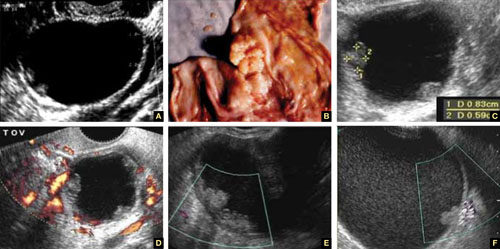

FIGURE 7 Endometriomas

Endometriomas have low echogenicity. A. Unilateral, unilocular cyst with thin walls. B. Bilateral endometriomas. C. Blood flow in a solid or papillary component of the endometrioma is an occasional finding. It should be investigated further because of the risk that it represents endometrioid cancer.

Endometriomas do not resolve; they usually require surgical excision, although very small ones wholly contained within an ovary are often managed medically or expectantly.

These masses rarely (<1%) give rise to endometrioid carcinoma. Should an endometrioma contain papillae with blood vessels, it is extremely suspicious for endometrioid cancer.

FIGURE 8 Cystic fibromas

A. Sonographic image shows a thin wall and hyperechoic, small mural nodules. B. Macroscopic appearance of an area of internal papillary excrescences. C. Measurement of the small, mural nodules. D. Lack of blood flow in the small papillae, a typical finding on color or power Doppler. E, F. Blood flow in the wall of the cyst and in the mural nodules.

Ovarian fibromas

A fibroma is a slow-growing, benign, solid ovarian tumor. It usually has a cystic component and then is called a cystadenofibroma.

The cystic variety is filled with anechoic fluid and has a thin wall. However, its pathognomonic feature is the small (2–3 mm), extremely hyperechoic mural nodules (papillae) it contains (Figure 8A–C). In the overwhelming majority of cases, no blood vessels are detectable, and the mass is unilocular (Figure 8D–E). It can be recognized in the ovary by the semilunar shape of the tissue surrounding it (crescent sign). The differential diagnosis includes the simple (serous) cyst.

The solid fibroma has a myometrium-like texture, with few or no detectable blood vessels in the stroma. The differential diagnosis includes the Brenner tumor and the Krukenberg tumor.

According to a technology assessment from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), “conventional gray-scale ultrasonography is the most common imaging modality used to differentiate benign from malignant adnexal masses. Especially with the advent of high-frequency transvaginal probes, the quality of the images allows description of the gross anatomic features of the lesion.”8 This descriptive ability is limited, however, “by the great variability of macroscopic characteristics of both benign and malignant masses. Furthermore, the technique is operator dependent.”8

To overcome these challenges, some experts have developed ultrasonographic (US) morphologic scoring systems, which assign a value to individual characteristics. Lerner and colleagues devised a 4-point system:

| Characteristic | Points | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Wall structure | Smooth or small irregularities (<3 mm) | Solid or not applicable | Papillarities larger than 3 mm | |

| Shadowing | Yes | No | ||

| Septation | None or thin (<3 mm) | Thick (≥3 mm) | ||

| Echogenicity | Sonolucent or low-level echo or echogenic core | Mixed or high | ||

The mean point value for benign masses was 1.8; for tumors of low malignant potential it was 3.9; and for malignant tumors it was 5.6 (P < .0005). Lerner and associates proposed a cutoff of 3. A score of 3 or higher, they felt, would be most predictive of malignancy, with sensitivity of 96.8% and specificity of 77%. Positive and negative predictive values were 29.4% and 99.6%, respectively.9

Almost all published scoring systems are based upon or derived from one reported by Sassone and coworkers.10 The most important and practical feature of all scoring systems is their ability to rule out malignancy.

Morphology and Doppler: A synergistic combination

As the same AHRQ report points out, “all of the diagnostic tests and scoring systems we evaluated exhibited a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity—studies of a given test that reported higher sensitivity had lower specificity, and vice versa.”8 Among evaluation methods, the combination of US morphology scores and Doppler imaging achieved the highest pooled sensitivity and specificity scores in distinguishing benign and malignant adnexal masses in postmenopausal women: 86% and 91%, respectively, according to the AHRQ report.8

Compare these figures with those of:

- Bimanual pelvic examination (45% and 90%, respectively)

- Doppler resistance index (72% and 90%)

- Doppler pulsatility index (80% and 73%)

- presence of blood vessels (88% and 78%).

The combination of US morphology scores and Doppler was comparable to the pooled sensitivity and specificity of magnetic resonance imaging (91% and 88%, respectively) and superior to computed tomography (90% and 75%, respectively).

Why the need to know?

Discrimination between benign and malignant masses serves a number of purposes, depending on the setting.

For example, if a symptomatic woman is found to have an adnexal mass, it is important to identify the type of mass causing the symptoms to determine the best course of treatment. And because surgery may be one of the treatment options, it is helpful to know whether a mass is likely to be malignant so that the patient can be referred to a specialist or center that has optimal surgical expertise.8

Some asymptomatic masses may be identified during the annual bimanual pelvic examination recommended by ACOG or during pregnancy-related US imaging. In this setting, it is important to ascertain whether the mass is likely to be malignant so that the patient can be referred to a specialist, if necessary. In addition, thorough assessment of the mass can help “avoid unnecessary diagnostic procedures, including surgery, and anxiety in women with asymptomatic, nonmalignant conditions. In some cases, there may be a rationale for removing certain asymptomatic benign lesions, including prevention of malignant transformation; prevention of ovarian torsion”; and prevention of rupture. Surgery may also be appropriate to avert the need for more complicated surgery in the future or to enhance fertility.8 —Janelle Yates, Senior Editor